Archaeology & History

A Cache of Ancient, Finely Decorated Scepters at the Hermitage Museum Are Now Thought to Be Straws for Drinking Beer

A paper describes them as "the earliest material evidence of drinking through long tubes."

A paper describes them as "the earliest material evidence of drinking through long tubes."

Sarah Cascone

Experts have a new theory about a cache of Early Bronze Age gold and silver objects unearthed by Russian archaeologist Nikolai Veselovsky way back in 1897: the long, thin tubes were actually ancient straws used for communally drinking beer—kind of like an over-the-top fishbowl cocktail.

If so, the tubes would be the oldest drinking straws ever found by a full millennia. The practice is likely much older, however, as there are artworks that date to the fifth or fourth millennia B.C. that seem depict people drinking from straws.

Veselovsky found the tubes near Maikop, a village in the northwestern Caucasus, in a kurgan burial mound dating to about 5,500 years ago. One of the most richly furnished burials of its kind, the grave had three compartments, each containing an adult body in the fetal position.

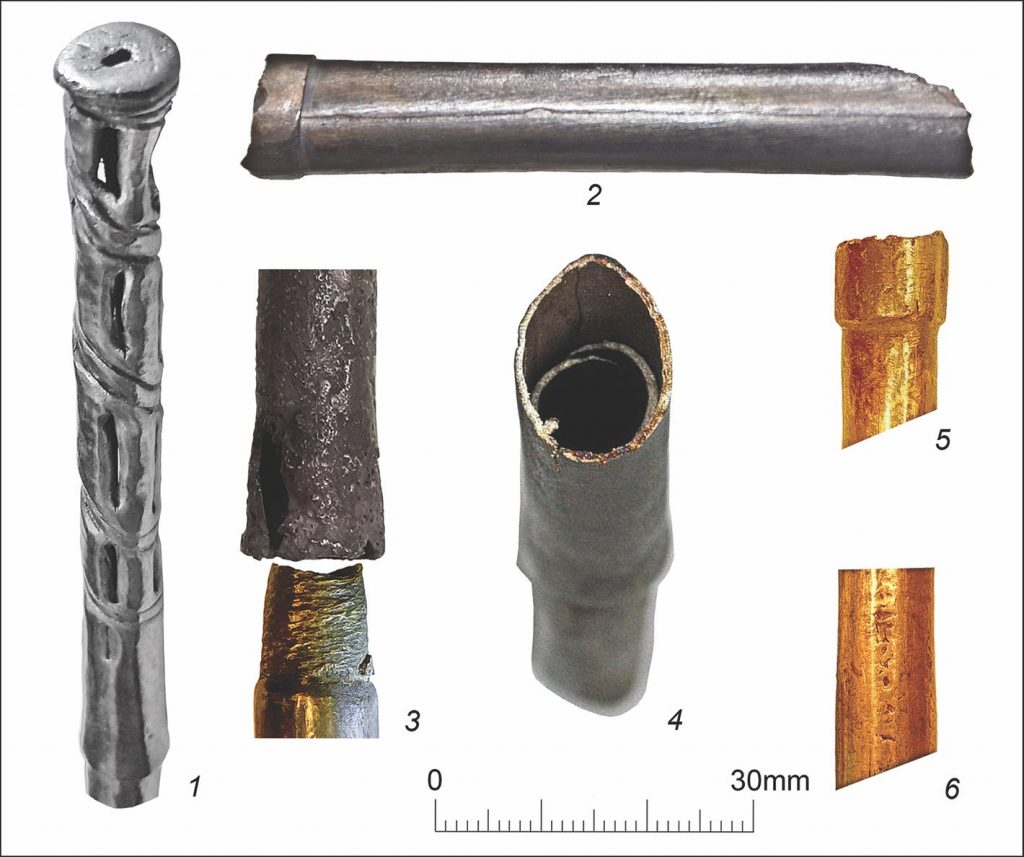

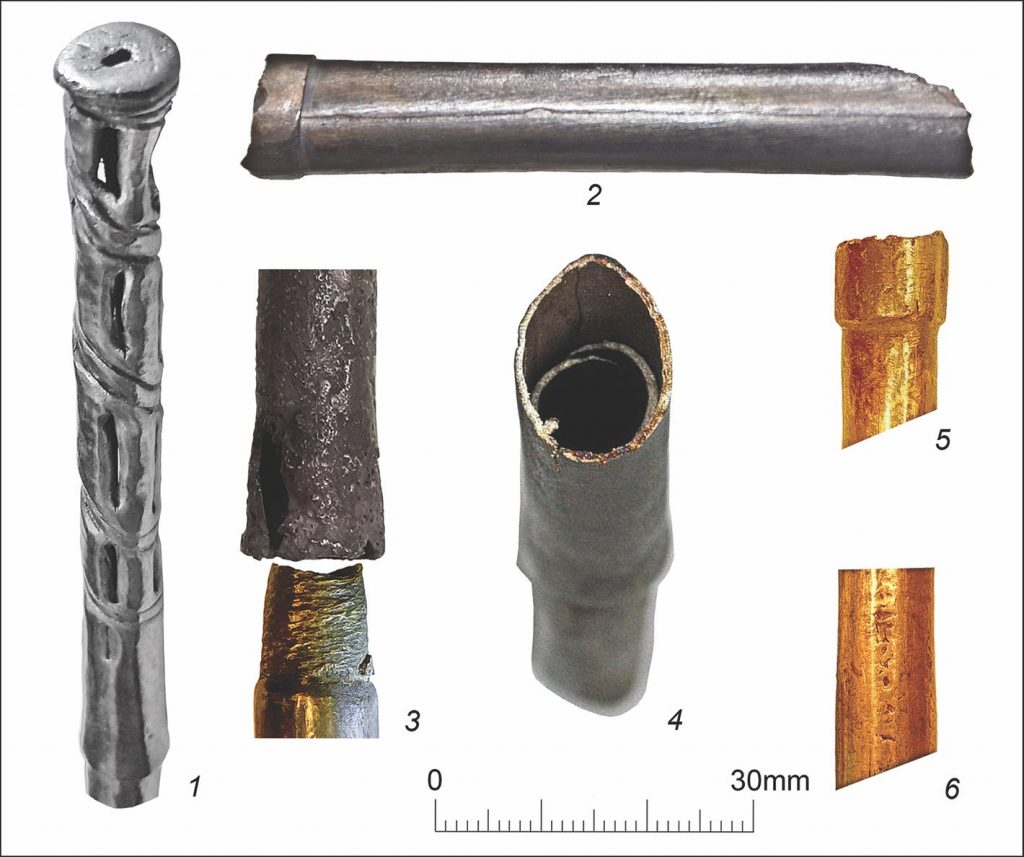

The eight tubes, now part of the collection of the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, were in the largest compartment. Decorated with animal figurines such as bulls, historians previously suspected that the tubes, which measured over a foot long, were some kind of status marker, such as a scepter.

The eight long, thin drinking straws found at the Maikop kurgan burial mound featured bull figurines. Image by Viktor Trifonov.

But Viktor Trifonov, an archaeology researcher at St. Petersburg’s Russian Academy of Sciences, had doubted that explanation for the better part of a decade. If the objects really were scepters, the animal figures on the tubes would have been upside down. And why, he wondered, were these Sumerian luxury grave goods hollow?

“I decided to check if there was any residue left from the beverage inside the Maikop tubes in the Hermitage,” he told Inverse. “Everything else fell into place when my teammates found the starch, phytoliths, and pollen grains inside the filter.”

How could barley starch residue have gotten into the tubes? The best explanation might be that they were used to drink beer, which the Sumerians likely started brewing some 13,000 years ago. And the pollen traces could have come from herbs and lime flowers used to flavor the beer.

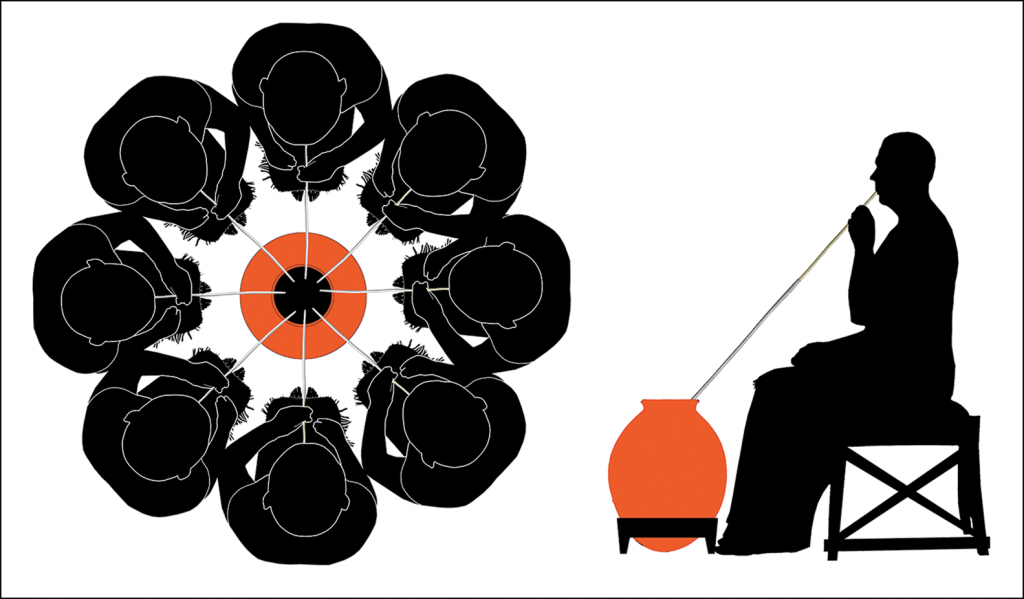

“The common ancient Sumerian implement for consuming beer was a tube made of a long reed, allowing the user to sit or even stand and drink from a large vessel positioned on a low pedestal,” Trifonov wrote in a paper, “Party Like a Sumerian,” published in the most recent issue of the journal Antiquity.

The Maidan aristocrats of the northern Caucasian, in turn, were very influenced by the culture of the great civilizations of the Near East:

If our interpretation is correct, these represent the earliest known drinking tubes, recovered not from the heart of the ancient Near East, but from the remote periphery of that world, in the northern Caucasus. While this does not mean that drinking tubes were invented in the Caucasus, it implies long-distance contacts, and that by the middle of the fourth millennium BC, these devices had become part of local funerary practices.

Reconstructed use of the drinking straws found at the Maikop kurgan burial mound. Image by Viktor Trifonov.

The tubes tapered to a pointy tip at one end, which could have been used to insert a reed strainer that would have filtered out sediment from the beer. If the tubes were straws, they would have been oriented pointy side down, so that the animal sculptures were upright for the drinkers—who were almost certainly imbibing as part of a social event.

“Contemporaneous images of banqueting scenes… frequently show two individuals flanking a large vessel, each with a tube held to their mouth and the other end inside the vessel. Often two to four more straws are depicted protruding from the same vessel,” Trifonov added. “The set of eight drinking tubes in the Maikop tomb may therefore represent the feasting equipment for eight individuals, who could have sat to drink beer from the single, large jar found in the tomb.”

Cheers to that!