Law & Politics

In a Landmark Ruling Against the Andy Warhol Foundation, the Supreme Court Has Sided With Photographer Lynn Goldsmith

The court found that Goldsmith was 'entitled to copyright protection, even against famous artists.'

The court found that Goldsmith was 'entitled to copyright protection, even against famous artists.'

Sarah Cascone

For months, the art world has waited with bated breath for the Supreme Court to issue a verdict in the closely followed case of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts versus Lynn Goldsmith. Today, the justices ruled seven-to-two in favor of the photographer, finding that an Andy Warhol portrait violated her copyright for her original photograph of the late musician Prince.

“Goldsmith’s original works, like those of other photographers, are entitled to copyright protection, even against famous artists,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in the majority opinion.

Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Elena Kagan stood alone in their dissent, CNN reported, writing that the ruling “will stifle creativity of every sort. It will impede new art and music and literature. It will thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge. It will make our world poorer.”

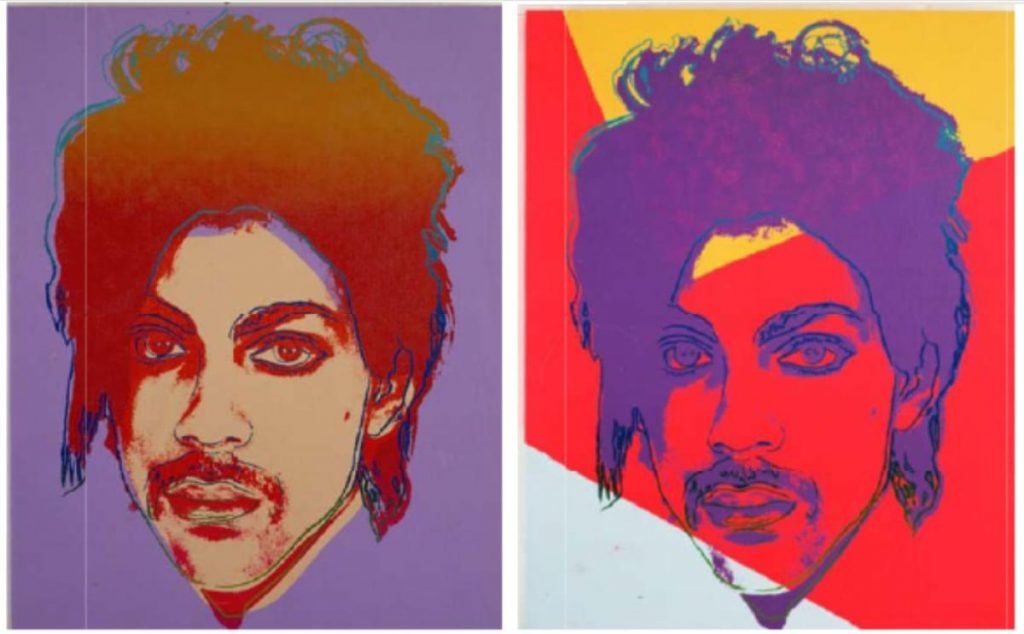

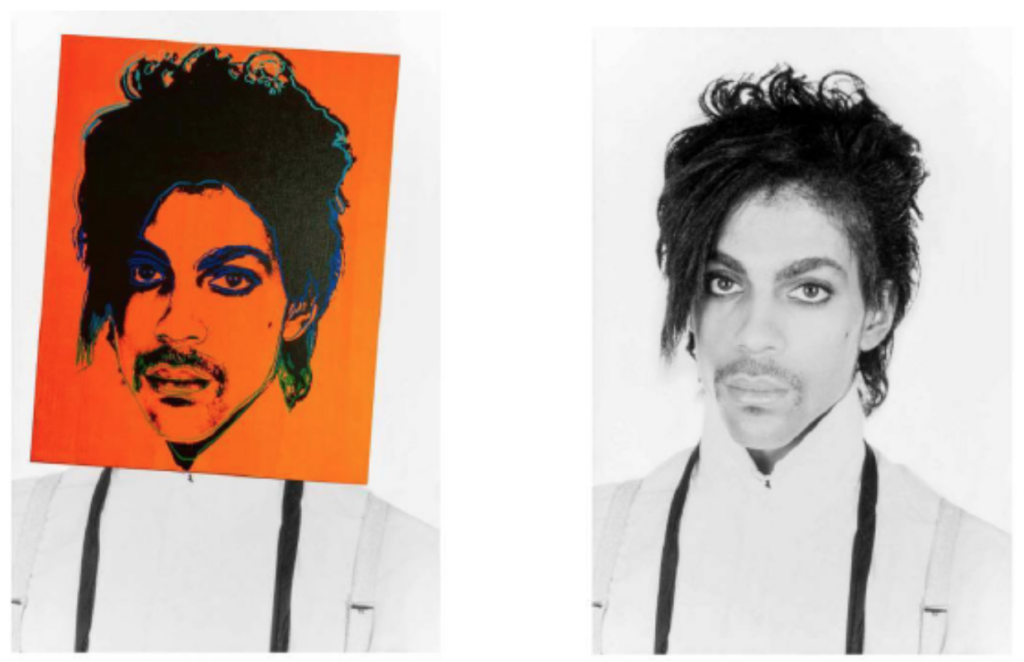

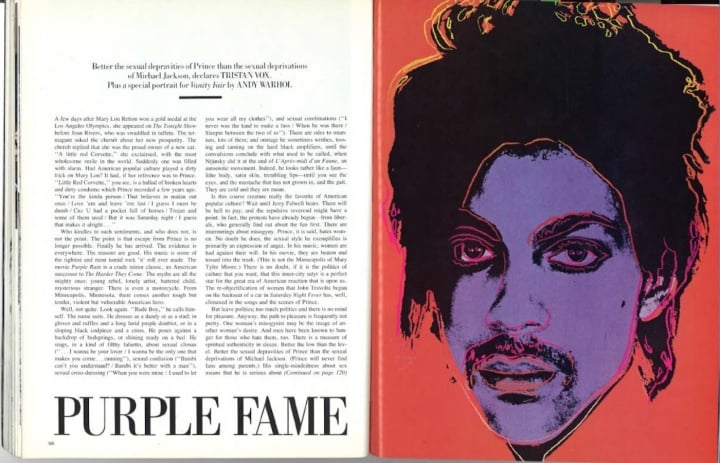

Warhol created a series of 14 silkscreen prints and two pencil drawings in 1984, each based on an unpublished image Goldsmith took of the young Prince in 1981 on assignment for Newsweek. Condé Nast had paid the photographer $400 for one-time use of her image as an “artist reference” for Warhol’s illustration in the article “Purple Fame.”

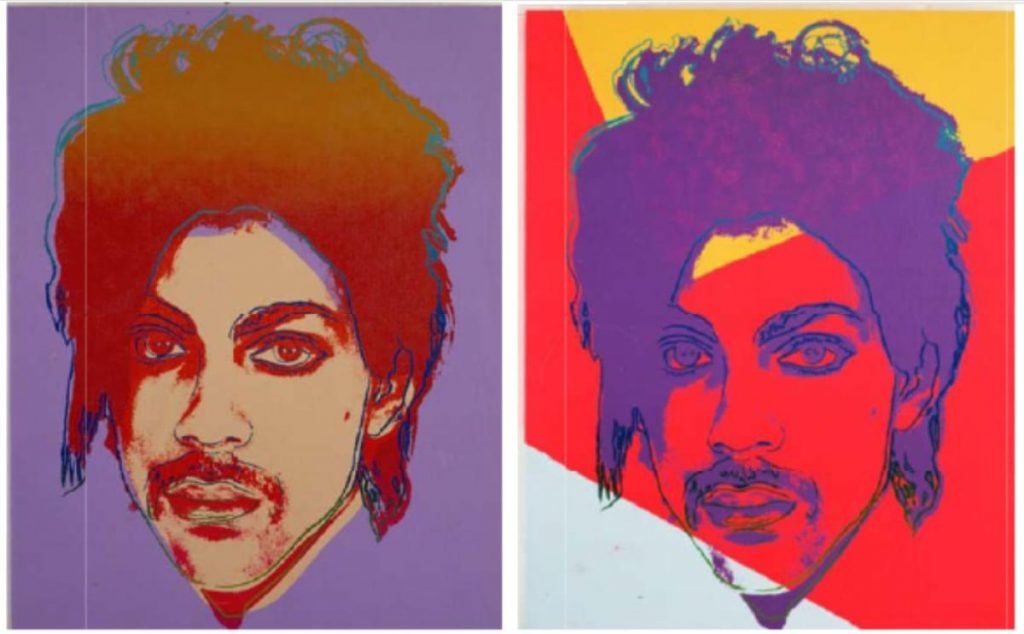

Andy Warhol’s Prince portrait overlaid on top of the original Lynn Goldsmith photograph of the musician, as reproduced in court documents.

The lawsuit surrounding the works blew up following Prince’s death in 2016, when Vanity Fair published a special commemorative issue in his honor. On the cover, the magazine displayed a second Warhol portrait from the series, titled Orange Prince, paying the late artist’s foundation $10,000 for usage.

Goldsmith wasn’t paid or credited, but she recognized her work. It was the first time she had become aware of the Pop artist’s Prince series, and she was immediately concerned that it violated her copyright.

“I am thrilled by today’s decision and thankful to the Supreme Court for hearing our side of the story,” Goldsmith told Artnet News in an email. “This is a great day for photographers and other artists who make a living by licensing their art.”

Andy Warhol’s Prince illustration based on the Lynn Goldsmith photograph as it appeared in Vanity Fair, here reproduced in court documents.

The case was something of a David and Goliath battle, with Goldsmith—who actually countersued the foundation for infringement after they sought a declaratory judgement that the portrait was fair use—launching a GoFundMe to cover what she predicated in 2019 to be up to $2.5 million in legal fees.

“This legal battle has been a long road at great emotional and financial impact upon me and my family,” Goldsmith added. “I felt I had to risk everything we had financially in order fight in the courts for protection of my rights and those of all in the arts against those who would infringe. I hope this SCOTUS ruling is a lesson that people should not shy away from legally standing up for their rights when organizations, foundations, or individuals who have greater financial resources intimidate them with legal costs.”

But there were many artists and creatives, including Conceptual collagist and graphic designer Barbara Kruger, who believed that Warhol’s portrait was fair use, and to rule otherwise could have a chilling effect on artistic creativity. On the other hand, the U.S. Copyright Office sided with Goldsmith, submitting an amicus brief to the court warning that failing to protect her copyright could open up the door to rampant copying.

The ruling appears to have come down to the “purpose and character” of the two works in question. The court found that both Goldsmith’s original photograph and Warhol’s portrait serve the same purpose, as magazine illustrations, with a commercial use. In fact, People had also published a commemorative Prince magazine, and had paid Goldsmith $1,000 for her photograph to appear on the cover.

Lynn Goldsmith’s photo for a GoFundMe supporting her her legal battle against the Andy Warhol Foundation. Photo courtesy of Lynn Goldsmith.

The ruling cautions that this interpretation “does not mean that all of Warhol’s derivative works, nor all uses of them, give rise to the same fair use analysis,” but it does tighten the limits of fair use moving forward.

“We respectfully disagree with the court’s ruling that the 2016 licensing of Orange Prince was not protected by the fair use doctrine,” the foundation’s president, Joel Wachs, told Artnet News in an email. “At the same time, we welcome the court’s clarification that its decision is limited to that single licensing and does not question the legality of Andy Warhol’s creation of the Prince Series in 1984.”

“I think it’s a significant contraction of where the court was,” New York University law professor Amy Adler, who had contributed to an amicus brief from art law professors in support of the Warhol Foundation, told Artnet News. “I think it is going to significantly limit the amount of borrowing and building on previous works that that artists will engage in. The court seems less interested now in the artistic contribution of the second work and much more interested in commercial concerns.”

Initially, the District Court had ruled in the foundation’s favor, declaring that Warhol had transformed Goldsmith’s photograph by imbuing it with new meaning as an icon of celebrity. The Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reversed that decision, insisting that “the district judge should not assume the role of art critic.” Now, the appeal to SCOTUS has decided the matter once and for all.