Law & Politics

Barbara Kruger, Robert Storr, and the U.S. Copyright Office Have Filed Briefs in the Supreme Court’s Historic Andy Warhol Copyright Case

The case is headed to the Supreme Court in October.

The case is headed to the Supreme Court in October.

Sarah Cascone

The U.S. Copyright Office, art critic Robert Storr, and artist Barbara Kruger are all weighing in on the consequential Andy Warhol lawsuit headed to the Supreme Court this October.

The case, for which over three-dozen figures and organizations—many high profile—have submitted amicus briefs to the court, is expected to have major ramifications for the future of fair use, copyright, and how the country balances the need to protect artists’ rights without stifling the creativity of others.

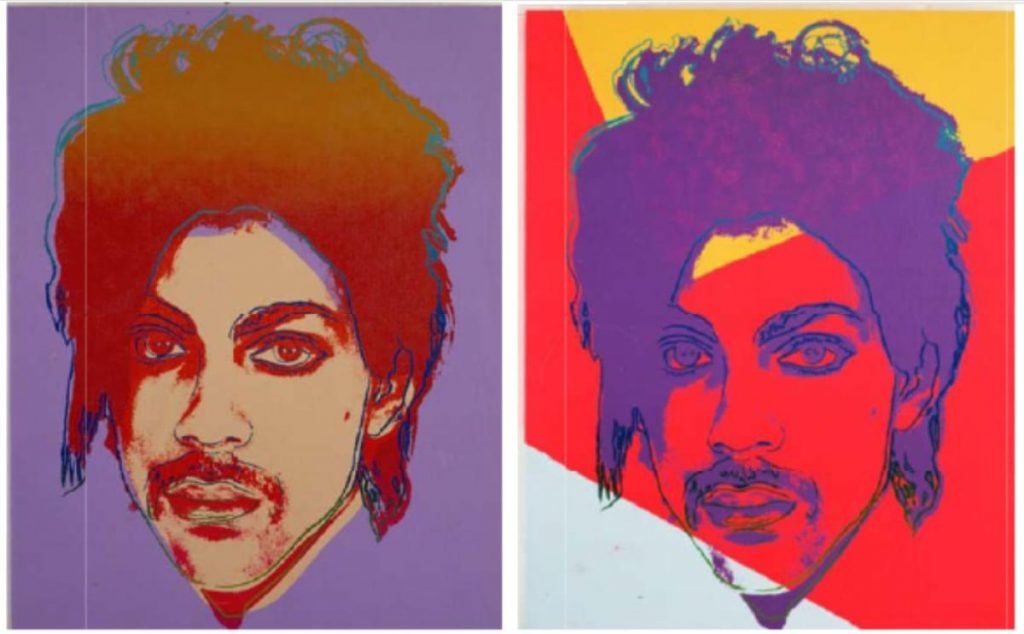

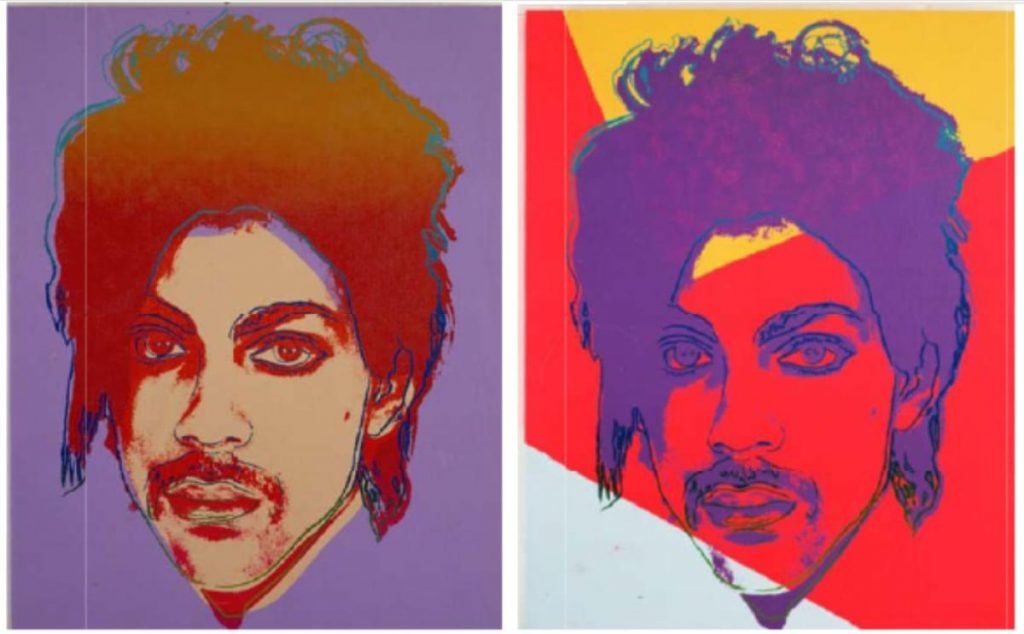

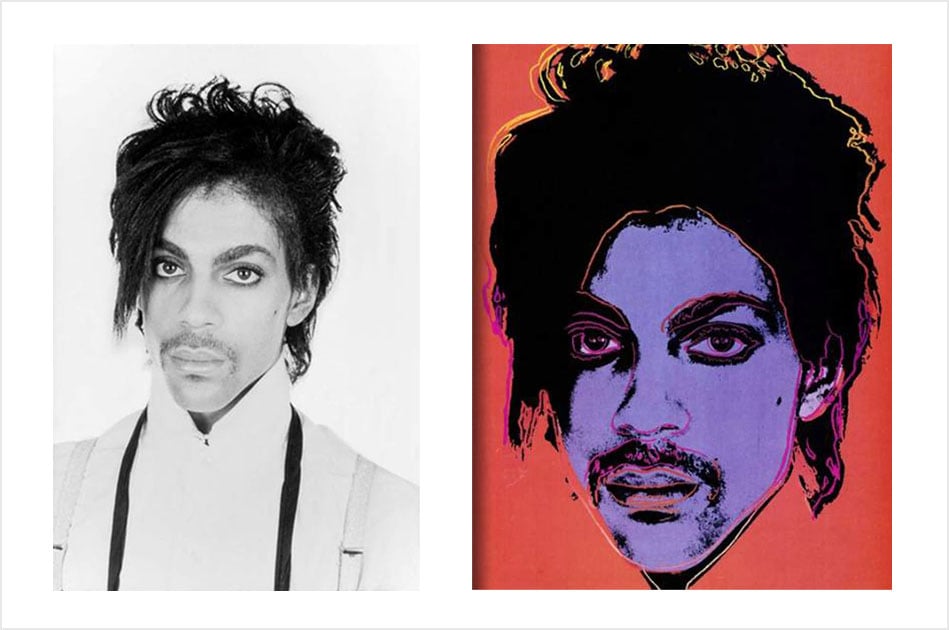

At the center of the dispute is a photograph of the singer Prince, taken in 1981 by Lynn Goldsmith, that Warhol later used as the basis for a silkscreen series.

The Warhol Foundation is currently appealing a 2021 verdict which found that Warhol’s Prince work did not significantly transform the original photograph, thus violating Goldsmith’s copyright.

That ruling reversed a lower court decision in 2019 which found that Warhol did, in fact, substantially change the message behind Goldsmith’s image of Prince, presenting, in his instantly recognizable style, a celebrity icon devoid of the vulnerability of the original photograph.

The U.S. Copyright Office is among those that disagree with that view. If Warhol’s work is considered transformative, then “countless secondary uses that currently require licensing would become presumptively fair,” the office wrote. “Take a songwriter who overlaid new lyrics onto a pre-existing musical composition—not in an attempt at parody, but simply to avoid composing a new tune—and then sought to commercially exploit her own song in the same markets as the original.”

Lynn Goldsmith’s photo of Prince and the Andy Warhol artwork derived from it.

The Copyright Office cited the 1989 Supreme Court case Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, which found that copying “to get attention or to avoid the drudgery in working up something fresh” is likely infringing.

The Warhol image of Prince came about as the result of an illustration commission for Vanity Fair, which paid Goldsmith $400 on a one-time license to use her photograph as the basis for the work published in its November 1984 issue. Goldsmith was credited for the illustration’s source photograph.

Even though the license specified that there were no other usage rights granted, Warhol continued to use the source material, ultimately making a whole series of 16 Prince works. When the musician died in 2016, Conde Nast paid the Warhol Foundation $10,000 to license a previously unpublished “Orange Prince” from the series—this time without credit to Goldsmith.

When she reached out about the use of her copyrighted image, the Warhol Foundation responded with a lawsuit, asking the court to declare that the series was not infringing.

The foundation claims that the Warhol image presents a different vision of Prince as a celebrity icon, compared to the vulnerability that’s central to the original photograph. Moreover, the market for prints of Goldsmith’s photographs is completely different than that of Warhol silkscreens, which routinely sell for millions.

However, the Conde Nast article that triggered the current legal dispute could have just as easily used the original Goldsmith photograph as the Prince artwork.

“The problem here, however, was not simply that the essential elements of the Goldsmith photograph were recognizable in the ‘Orange Prince’ image,” the Copyright Office wrote. “Rather, in commercially licensing ‘Orange Prince’ to Condé Nast, petitioner used those elements for the same purpose as in the Goldsmith photograph itself.”

Joining the U.S. Copyright Office in siding with Goldsmith is the American Society of Media Photographers (ASMP), the National Press Photographer’s Association (NPPA), and American Photographic Artists (APA), as well as the Association of American Publishers and other organizations and individuals.

“The fair use defense was never meant to give infringers a pass so long as they claim some new subjective ‘meaning or message’ in their derivative use regardless of how it is used,” the NPPA and ASMP argued. “Rather, any purported new meaning or message is only relevant in the context of a qualitatively different purpose or use than that of the original.”

Among those weighing in on the side of the Warhol Foundation are Kruger and curator and Storr, who wrote a joint amicus brief.

“The court of appeals’ surprising and restrictive approach to fair use,” the two wrote, “thwarts the constitution’s and copyright law’s goal of promoting creativity and is anathema to centuries of established artistic practice of expressing new meaning through the integration of pre-existing works of art into new ones.”

Still other artists fear that a judgment in favor of Warhol could actually harm them.

Such a ruling “poses an existential threat to photographers,” wrote Jeffrey Sedlik, a photographer, in his amicus brief. An expert witness in the case, Sedlik is newly embroiled in a high-profile copyright case over his portrait of jazz legend Miles Davis, which celebrity tattoo artist Kat Von D inked on a client and featured on her social media platform.

“We are not talking about news, criticism, scholarship, parody, or other traditional mainstays of fair use. This is the taking of art to make other art,” Sedlik wrote in his brief. “It takes considerable time to rewrite a book, rearrange a song, recode an operating system, or re-edit a movie. But a novice with a computer, smartphone or crayon can alter a photograph in seconds.”

Photographers and other artists, the NPPA and ASMP wrote, “are watching this case closely as their livelihood depends on it.”