Art World

Art Bites: How a $20-Million Art Sale Was Won in a Game of Rock Paper Scissors

A Japanese firm used this unorthodox gamble to decide which auction house would sell off its art collection.

Across 200 years of competition, Sotheby’s and Christie’s have adopted daring and surreptitious tactics in pursuit of securing consignments. None stranger, however, than those employed in a Tokyo conference room in 2005.

That year, Maspro Denkoh Corporation, an electronics firm based near Nagoya, Japan, had decided to sell off its European art collection to fund further acquisitions of Japanese ceramics. Among the 37 Impressionist and Modern paintings were several that would make for star lots in an upcoming spring sale.

The problem was, Maspro president Takashi Hashiyama, couldn’t decide which of the two auction houses should have the privilege of selling the $20 million collection.

Hashiyama might have split the collection, or sought out sales via the private market. Instead, he demanded that the art world behemoths do battle in a playground favorite: rock paper scissors. The auction houses were given the weekend to prepare before reporting to the company’s Tokyo office.

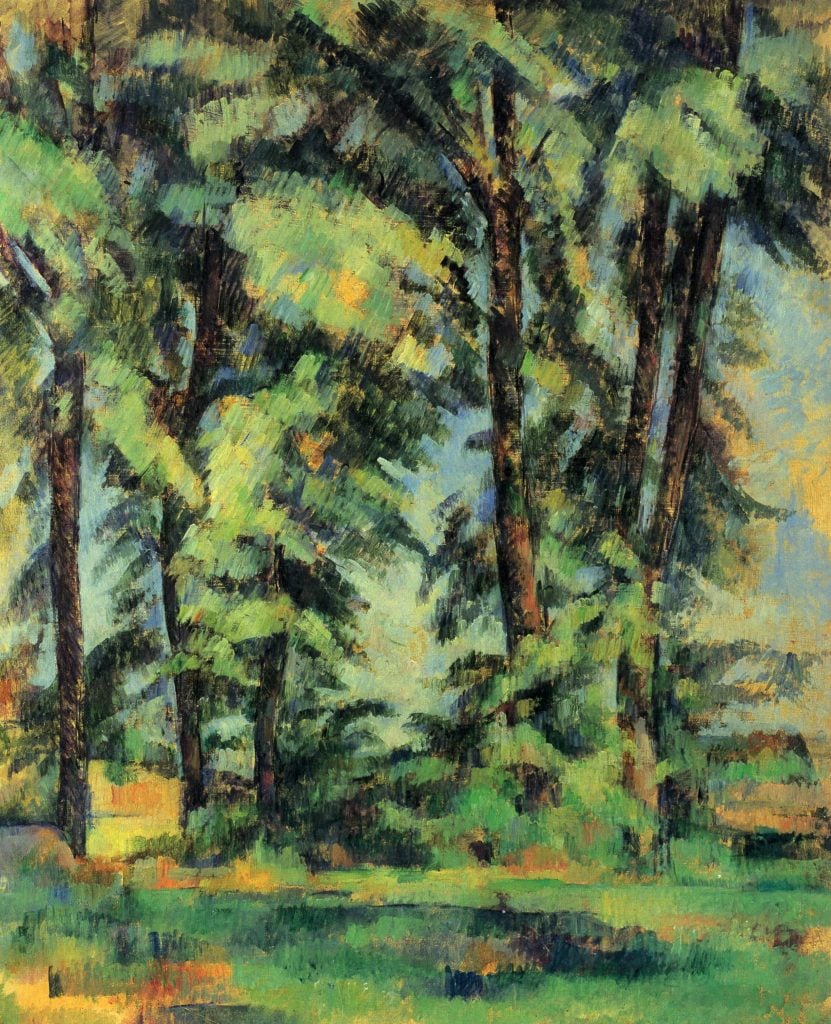

Paul Cézanne, Les Grands Arbres au Jas de Bouffan (1885–87). Photo: Wikipedia Commons.

The rivals settled on drastically different approaches. Sotheby’s considered the game governed by chance, one seemingly only slightly less random than a coin flip, and saw no reason to develop a strategy.

Christie’s, on the other hand, took the task seriously. Kanae Ishibashi, then president of Christie’s in Japan, researched the game’s psychology online and sought the insights of a colleague’s children. The advice was clear: throwing a rock was an alpha move, one to be avoided; throwing paper was deemed too passive, too obvious. The best bet was scissors.

Ahead of the meeting Ishibashi prayed, sprinkled salt (a Japanese superstition believed to drive away bad luck), and carried a lucky charm.

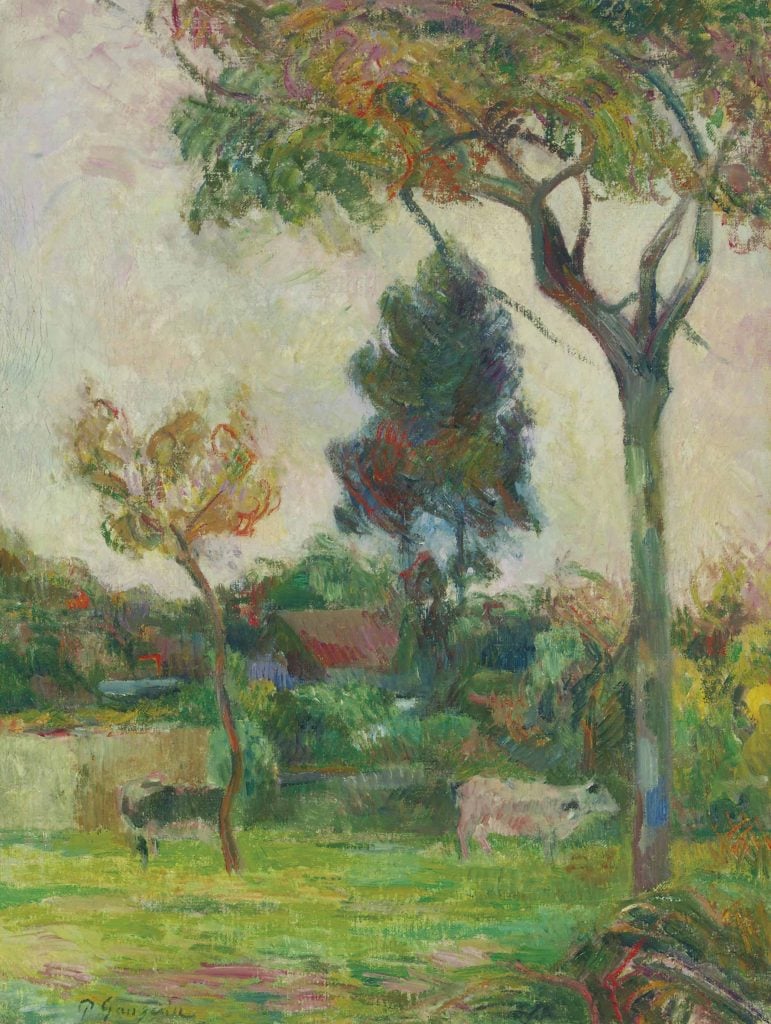

Paul Gauguin, Deux vaches au pré (1884). Photo: Wikipedia Commons.

On Monday morning, representatives from Sotheby’s and Christie’s reported to Maspro’s offices and were sat at opposite ends of a long conference table. With the oversight of a Maspro accountant, the teams were asked to write down their decision on a piece of paper. Christie’s scissors beat Sotheby’s paper.

Despite the doubtless satisfaction in besting their rival, the auction itself was only a moderate success.

Cézanne’s Les grands arbres au Jas de Bouffan, a landscape of vibrant greens and blues that captures his move away from Impressionism in the 1880s, sold for $11.8 million, below its low estimate of $12 million. Pablo Picasso’s Boulevard de Clichy, a dashed street scene painted as 19-year-old during his second stint in Paris, reached $1.7 million, below its low estimate of $1.8 million. Christie’s bought in Paul Gauguin’s Deux vaches au pré.

All the same, it’s a story that has gone down in auction lore.

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history. These delightful nuggets shed light on the lives of famed artists and decode their practices, while adding new layers of intrigue to celebrated masterpieces.