People

‘The Track Record Is Disastrous’: Musician Nick Cave on His Cautious Return to Art

The lead singer of the Bad Seeds reflects on art, music, and morals in the wake of unveiling his first solo exhibition.

The lead singer of the Bad Seeds reflects on art, music, and morals in the wake of unveiling his first solo exhibition.

Kate Brown

“I don’t know anything about the art world, other than that I was at an opening last night,” Nick Cave tells me from a private office at Xavier Hufkens in Brussels, the morning after his show opened. “It is interesting and quite weird that I am even here,” he adds, his Australian accent softened from years of living and moving around the globe but ever-present in the inflected vowels.

I might agree. The bustling gallery, a strikingly modern building of incongruently stacked floors that sprouts from the side of an 19th century house on rue St-Georges, is the site of the famed musician’s first solo exhibition. As the lead singer of the Australian post-punk band the Bad Seeds since the early 1980s, known for his cavernous vocals and uniquely charged and ambivalent lyrics, he is an icon.

With that legacy in mind, it is indeed curious to see Cave pop up in the so-termed art world—but only a bit curious. One can tell from viewing his work that Cave is serious about making art. In “The Devil — A Life,” a honed and aesthetic sensibility is apparent in well-executed ceramics, which cleverly reference Victorian porcelain but which feature Lucifer as the main subject. The works relay a tempestuous tale that oscillates between good and evil and stirs corners of empathy in a strange sort of way, a way we might have felt before from his music. Cave loads in a lot of symbolism and draws on topics around death and violence, but also love and religion. Darkness is always paired with light.

Nick Cave in the studio. Photo: Liv and Dom. Courtesy: Nick Cave and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels

Much earlier in Australia during a rebellious youth, Cave went to art school, though he ended up leaving it behind in pursuit of music. “The band just kind of took off but my art career didn’t because I was preoccupied,” he recalls. It was in those years, though, that he learned to glaze and fire ceramics, even if it was not a skill he would tap into until more than four decades later. “What I had always wanted to do was be a painter. I loved painting and I learned about it, but my art school experience wasn’t particularly fruitful, shall we say? The band just ate up everything.”

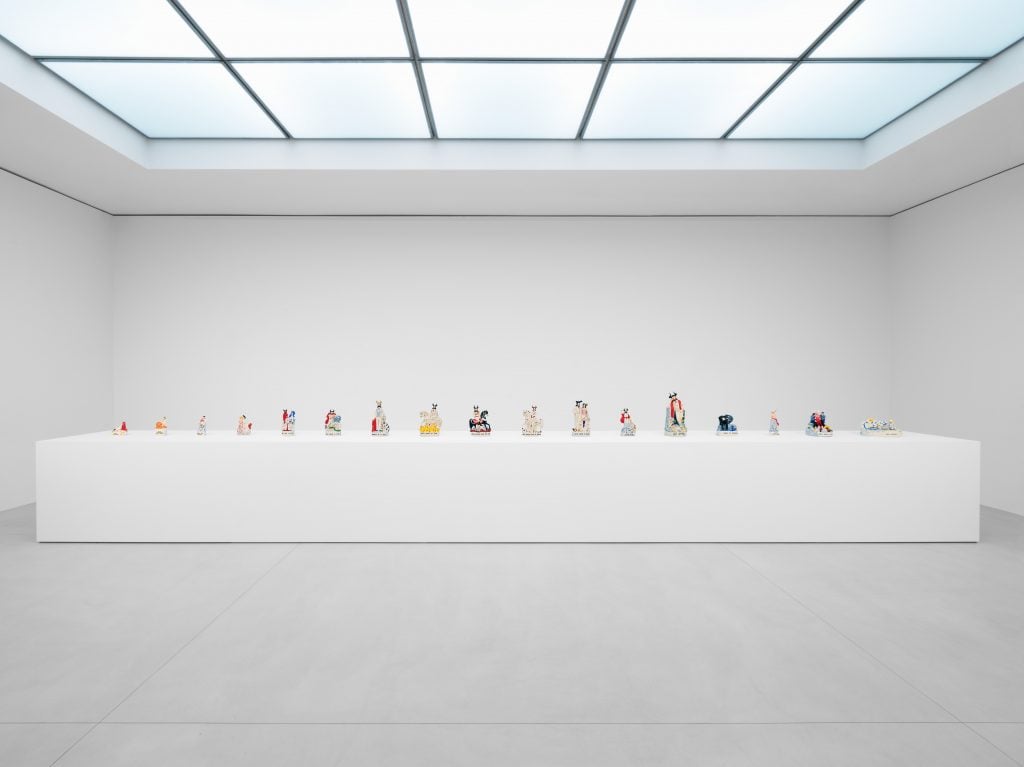

It still takes up the bulk of his time. Concurrently to the preparation of this show, Cave dropped a new single with the Bad Seeds, which will feature on their 18th album that comes out this year. Wild God is the name of the new track and I can almost see it as a sibling to these ceramics; lined up in the gallery on a large plinth, they seem to wink to the Stations of the Cross—but it is the life phases of the devil in focus.

The works are made in the style of Staffordshire ceramics with flat backs, popular decor items that were often hung in the homes of the English middle class, but Cave’s are much more vivid in color, though that particular lustre is the same. In the The Devil Awakens, the devil (easily identifiable by his devil horns) is in clothes reminiscent of angel Gabriel, with a gold trim, resting on the back of a bright red steed. A few scenes on, an older Devil is bleeding out, held by two gentlemen as he cranes his neck in pain while two lambs (in christian iconography, there is usually only one, and so this doppelganger effect further weirds the scene) into the distance. In yet another, the devil kills his firstborn and in another he marries a wife. If these play at being morality tales, the moral is unclear, our protagonist problematic.

Installation view of “The Devil – A Life.” Courtesy: Nick Cave and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels

Cave doesn’t take responsibility for the story depicted per se. The artworks “seem to know a lot more about what’s going on than the artists themselves,” Cave tells me. “I was lured quite unwittingly along a narrative path that started to ask massive questions of me. What started off as pure whimsy ended up speaking to me about things that my songs haven’t been able to.”

These larger standalone pieces evolved out of so-called spill vases that he had initially started out making—Cave’s interpretations of Victorian vases that would hold a roll of paper or a twig, used to transfer a flame from one place to another in the house. “I wanted to make these because I wanted my work to be well and truly craft, so that it would not put me into the art world,” Cave says. “On some level, it is the last place I wanted to end up as a musician—the track record is disastrous. I went to art school [and so] I had a lot of artist friends and making art was a serious thing; they put their lives into this. This idea that you can knock out some paintings between tours felt like a kind of a vanity. That’s why I wanted to make craft things.”

Installation view of “The Devil – A Life.” Courtesy: Nick Cave and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels

Their folkloric style and craftiness, however, is exactly what makes them appealing. In an art world where so much work is just about a clever elevator pitch, the works Cave has made are sincere, clearly the result of an inner world percolating outwards, and products of an interest in process and curiosity. Maybe that is the irony—Cave’s attempts to avoid being read as an artist as such landed him in an art gallery. And that in-between state of Staffordshire ceramics (which he actually collects himself) as neither high or low art is what makes them so interesting to the art world, but also to Cave. “They are a bridge between craft and art, essentially made to bring a little joy into people’s lives,” he says. “There is a naive innocence about them—no pretension.”

Singer Nick Cave performing in 2022. Photo: Pablo Gallardo/Redferns

Everything changed for everyone in 2020 Artists’ abilities to connect with their publics were drastically cut off and it changed the focus of Cave’s creativity too. “Suddenly, I couldn’t tour. I had a year off. And that was just the most extraordinary time.” First he wrote a book. Then he started to work in the studio on ceramics. “It had been 45 years since I had made something with my hands rather than with music or words. It was a beautiful feeling.”

“Weirdly, my mother died the day I started making these,” he said of this new trajectory of work. “I almost canceled, but my wife Susie said ‘go to the studio, do your work.’ Back in art art school, he’d made a few figurines, which adorned his mother’s house until she died.

Persevering with creative work no matter what tragedies life throws at you is something Cave writes about in The Red Hand Files, an approachable blog where he responds to fans’ inquiries, often lending his thoughts and advice—he calls it an exercise in empathy. He plows through mail and selectively responds, publishing the questions and the answers. It is disarmingly intimate. Because Cave has lost two of his sons (his 15 year old Arthur died 2015, and in 2022, he lost his 31-year-old son Jethro), often those who write him are grieving and trying to cope with similar losses. “There is this great river of suffering that runs through [The Red Hand Files],” Cave says.

Nick Cave Devil Bleeds to Death (2024). Courtesy: Nick Cave and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels

But people bring forward all kinds of issues, some related to art. In February, for example, a person named Dan had written Cave asking help with continuing to make art in a world marked by “war and cruelty,” while a person named Tam wondered how to make art without a muse. Reading his answers, you can get some insight into how Cave has managed to continue to work faced with his own personal devastations: “We are artists and we labour in the service of others,” he wrote back. “It is not something we do only if and when we feel motivated. We are duty-bound to do our job, like everyone else, because the space we occupy depends upon our participation and breaks down if we don’t.”

To Dan, he added that “yes, the world is sick, and yes it can be cruel, but it would be a whole lot sicker and a whole lot crueler… if it were not the beauty-makers wading through the blood and muck of things, whilst reaching skyward to draw down the very heavens themselves.”

To Tam, he noted: “muses are for losers!”

Nick Cave in the studio. Photo: Liv and Dom. Courtesy: Nick Cave and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels

Cave doesn’t give advice only to strangers—one of his close friends is the artist Thomas Houseago, who Cave tells me he visited from time to time at his large Los Angeles studio; Houseago, “for some bizarre reason,” respected Cave’s thoughts on his art. And then, mid-2020, Houseago had a nervous breakdown. In an interview I did with the painter and sculptor after he had recovered from a very traumatic near-death experience, Houseago had told me that Cave had been one of the people to help pull him out of the darkness, and get him back to his art-making. Cave says they helped each other.

“He could not paint, he could not do anything. I was having my problems, trying to get a record together and, as usual, in the early stages, nothing was really coming,” he recalls. “I said to Thomas, ‘Look, why don’t you paint me a picture? And I will write you a song.’ Suddenly, that became quite easy for both of us to do, because we were no longer personally responsible for our actions.”

Houseago made Cave a painting of a wild-looking purple flower, which Cave says seems to have been “rising out of the ashes.” Of Cave’s song, Houseago told me he read it as a prescient piece of music that foretold the January 6 riots.

Throughout their exchange, Houseage also encouraged Cave to carry on with his ceramics. “I sent him a photograph of the first one, the devil and the sailor. His roaring enthusiasm pushed the whole project along,” Cave remarks. Houseago also helped him see the works as a “legitimate artistic pursuit,” introduced Cave to Xavier Hufkens, “and here we are.” Together with another friend, actor Brad Pitt, Cave’s ceramics went on view at the Sara Hilden Art Museum in Finland. According to reports, the museum was supposed to only exhibit Houseago, but changed course after he persuaded the museum to add Pitt and Cave to the bill.

Visitors look at work by musician Nick Cave, in a show with Thomas Houseago and actor Brad Pitt at the Sara Hilde Art Museum in Tampere, Finland. Photo: Alessandro Rampazzo/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

My guess is that Cave would likely not agree with Houseago’s read on the song he wrote him, but he would not disagree either. He speaks fondly about the ability to have flexibility in music, about how “nothing is fixed,” and how “things can mean a different thing depending on how you sing it.”

The devil in his ceramic depictions, out of keeping with black-and-white portrays of good and evil, seems to represent a liminal space of reflection within the intensifying polemics and fraught climate of today’s world. Cave and I speak about the mood of moral outrage that seems to characterize the moment. “It is a huge societal problem, especially for young people,” he says of the online sphere in particular. “The centrist position, which I controversially hold—the capacity to hold two opposing ideas in my hand at the same time—is anathema. But we need to be able to do that.”

In one of the new figurines, Devil in Remorse, a horned devil sits hunched over, face in his palms. Here, the figure is depicted with a black tailored suit, with long legs and black hair combed back, in a style and dress not dissimilar to Cave himself. For an artist who has bared his soul in his music, these works are even more forthright. “Songs for me, essentially, always have been a way of speaking truth through a veil where you never have to be explicit. The more abstract and the more impressionistic you are with songwriting, the more interesting the songs actually are,” he says. “Now, you don’t get that with these figurines. They are what they are and I found that really exciting. There was no hiding.”