Analysis

How Auctions Became the Ultimate Form of Art Market Theater

The auction market has always been theatrical—but now, it’s more stage-managed than ever. Here’s what that means for buyers and sellers.

This article is part of the Artnet Intelligence Report Year Ahead 2024. Through in-depth analysis of last year’s market performance, the new edition paints a data-driven picture of the art world today, from the latest auction results to the artists and artworks leading the conversation.

On the seventh floor of Sotheby’s New York headquarters during a blisteringly cold night January, a glamorous crowd clinked champagne flutes and traded air kisses. They weren’t there for a high-stakes auction. Instead, they had gathered to celebrate a new Broadway musical about the life of the 20th-century artist Tamara de Lempicka. After the performance, actors pretended to be Sotheby’s staffers taking phone bids. Auctions have often been compared to theater for their drama and staging. That night, Broadway found itself inside an auction house, and Sotheby’s became a stage.

It was an apt metaphor for the current state of play in the auction business. Four years after the pandemic transformed insular evening sales into extravaganzas streamed live online, the industry has never been more theatrical. Tens of thousands of viewers tuned in to watch the marquee November sales, conducted by specialists in professional hair and makeup and recorded by roving video cameras worthy of a major broadcasting company.

The cast of the new Broadway musical “Lempicka” attended a launch event at Sotheby’s auction house in January. Courtesy of Kevin Doan.

That’s far from the only element of the production that is carefully stage-managed. “The auction room is more than ever before a public room for private transactions,” said the lawyer Thomas Danziger, who advises clients on high-value art deals. “It’s more like a Broadway performance than a traditional auction.”

A variety of factors, including a softening market and changing legal requirements, have united to make it increasingly difficult to discern what’s going on not only behind the curtain but also in front of it.

Prologue

Auctions’ lack of transparency is the stuff of urban legends and everyday reality. Every decade, it seems, brings a major scandal. In the 1980s, the corporation Cristallina S.A. sued Christie’s for setting the reserve—the secret minimum price sellers will accept—for several Impressionist paintings above their high estimates and then lying in the press when the works failed to sell. In the 1990s, an investigation into collusion between Christie’s and Sotheby’s toppled their chief executives and sent Sotheby’s then-owner, A. Alfred Taubman, to jail.

For decades, New York legislators sought to impose restrictions on auctioneers—specifically, on their use of the phantom bids, known as “chandelier bids,” claiming they could harm consumers. But auction houses persevered. After all, they’d been using the bids since at least the 19th century to build momentum in the room and protect the consignor.

The past decade has been a mixed bag for transparency. Know Your Client standards and anti-money- laundering regulations in the United States, European Union, and United Kingdom mean that sellers can no longer hide behind advisors, trusts, or limited liability companies because auction houses must identify the ultimate owner of an artwork. In 2016, New York City—home of the biggest art market in the world—told companies to disclose fees paid to third-party guarantors when reporting final prices.

Sotheby’s marquee evening sales have become streaming productions worthy of a major broadcasting company. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Two years later, a window into the health of the market closed when Sotheby’s was acquired by telecom magnate Patrick Drahi’s BidFair USA. Since then, the world’s three largest auction houses—Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Phillips—have been privately owned and not required to publicly report extensive financial results on a regular basis.

One of the biggest changes came in 2022, when New York City repealed a number of longstanding regulations on the auction industry, including the 2016 net price disclosure requirement. The changes, which went into effect over the past two years, removed restrictions on “chandelier” bidding past the reserve amount as well as requirements for marking guaranteed lots in the catalogues and setting estimates above the reserve. Auction houses also no longer required a license to operate. The move was framed as a citywide effort to boost small businesses after the pandemic; auction houses have claimed they did not lobby for the changes.

When the New York regulations were repealed, a chorus of voices raised concerns that auctions would become a Wild West. The Big Three houses say that they have, by and large, not changed their behavior. So far, auctioneers “seem to be acting as if guardrails are still in place,” Danziger said. “The big auction houses are steered like ocean liners, not speedboats, so any changes are slow to happen and are incremental in nature.”

The potential impact of these changes, and exactly what they involve, remain murky. But even fine-print adjustments can have profound consequences for the trade, for money made and lost. So we took a closer look at the sleight of hands occurring at different phases of the auction process. Here’s what has happened in the past and what could change in the future.

Act One: The Withdrawals

Onstage: The sell-through rate of a sale appears strong.

Backstage: Works are withdrawn if they look like they won’t sell—even in the middle of the auction.

The image of Sotheby’s global chairman Brooke Lampley delivering a pair of white gloves to an auctioneer at the end of a sale has become increasingly common in recent seasons. In November alone, Lampley awarded this symbol of auction perfection (when every lot finds a buyer) twice. But auction houses have many strategies to create the appearance of success, including withdrawing lots instead of letting them go unsold.

Auction houses are increasing their reliance on withdrawals to boost their sell-through rates (the ratio of sold to unsold works). Sotheby’s in particular has been using this strategy, and its unexpected announcement of withdrawn lots in the middle of a sale has sparked gasps and murmurs. “We realized there wasn’t a big stigma,” one auction house executive said. “If you know 99.9 percent that something isn’t going to sell, why keep it in?”

In May, the house withdrew the cover lot of the Now sale, Yoshitomo Nara’s Haze Days (1998), estimated at $12 million to $18 million, midway through the auction. The work accounted for more than a third of the sale’s original low estimate of $42 million.

Six months later, Sotheby’s withdrew eight lots, jointly estimated at $19.8 million, from its Modern art evening sale. As a result, the house was able to report a solid sell through rate of 94 percent (as opposed to 74 percent if those lots had failed to sell, according to Artnet News calculations). Christie’s said its withdrawal rate has been about 4 percent in the past few seasons, compared with 2 percent in 2018. Sotheby’s said it does not track its withdrawals.

For the players in the deal, there’s almost no downside. Consignors usually pay a fee to pull an item, but they are more likely to be able to resell the work later without the black mark of auction failure. And auction houses can erase the work from internet price databases, the auction house executive noted.

The danger is that this practice can create deceptively bullish auction statistics. The houses “are crafting a narrative that makes the art market look better than it is and their performance better than it is,” said the art advisor Wendy Cromwell.

Brooke Lampley, Sotheby’s global chairman, delivered white gloves to auctioneer Oliver Barker after a successful auction in Las Vegas in 2021. Photo by Denise Truscello/Getty Images for Sotheby’s.

Act Two: The Bidding

Onstage: A work attracts a flurry of bids.

Backstage: There may be less demand than you think.

Auctions are about ritual, gentility, and decorum. Auctioneer Jussi Pylkkänen always wore a purple Savile Row tie while presiding over an evening sale; Christopher Burge would down one shot of Scotch whiskey before taking the stage. Auctioneers have their lines, formally addressing prominent colleagues bidding in the room as “sir” and “madam.” (When a well-known buyer doesn’t have a paddle, the auctioneer will assure them, “Not to worry, we know who you are.”) And the players have their places: the Nahmad family of collector-traders is in the front row; the Acquavella clan is usually up in the skybox.

The repeal of the New York regulations meant that auction houses had more flexibility to stage-manage not only the evening’s script but also the bidding process. Previously, auctioneers were allowed to “chandelier bid” up to the reserve in an effort to stir up energy. You’ve seen it: an auctioneer opens the bidding below the low estimate and proceeds with a concatenation of bids, staring intensely into the distance. Those bids are not real. (Until 2022, the outcome of the Cristallina case in 1980 also assured that the reserve was set at or below the low estimate.) Insiders don’t get confused by it, but it can be misleading to newcomers. “You are replacing straightforward commerce with theater,” Danziger said.

Since New York City did away with restrictions on chandelier bidding in 2022, there’s nothing legally stopping auction houses from getting more creative. Technically, more than one specialist could execute a third-party guarantee, legal experts said. That means that instead of pulling the bids off the chandelier or from phantoms in the back of the room, auction-house employees can playact as a chorus of bidders, even though they are representing only one. The result—a fake bidding war—would make demand look deeper than it is.

Auctioneer Georgina Hilton sold the top lot of Christie’s 21st Century Evening Sale, Cy Twombly’s Untitled (Bacchus 1st Version II) (2004), on November 7, 2023. Christie’s Images Ltd. 2024.

Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips explicitly denied engaging in this practice. But a group of insiders who frequently place bids at auction said that they are proceeding on the assumption that it is happening and are accordingly skeptical of the depth of demand for certain—especially high-priced—works. Another person, who was involved in the consignment of a record-setting painting in November that ended up selling to the guarantor, recalled watching the flurry of bids and wondering to himself, “Are these real?”

Act Three: The Disclosures

Onstage: Financial arrangements are revealed in an orderly, timely manner.

Backstage: It’s a lot more chaotic.

Whether glamorous or modest, auctions typically start with housekeeping rules recited by an auctioneer. Those rules would normally be found in fine print and indicated by mysterious symbols in the back of the catalogues. Under the now-repealed regulations, the announcements were rote, mandated by the authorities, who saw them as key to leveling the playing field for buyers and sellers. If you listened carefully, you’d hear the rules on chandelier bidding, reserves, and, in the past decade, an ever-growing list of last-minute third-party guarantees and withdrawals.

Where once there was consistency in how Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips disclosed key information to market participants, now there’s cacophony. In November, for example, every house sang its own tune.

At Phillips, the auctioneer listed the withdrawals ahead of the sale but not the latest third-party guarantees (those were mentioned just before the lot came up on the block). Meanwhile, Sotheby’s instructed its audience to consult the online auction catalogue for the latest changes, which is not exactly user-friendly for those focused on the proceedings.

Christie’s continued its longtime practice of announcing last-minute third-party guarantees from the rostrum before the evening auctions began. But the house failed to update its online catalogue with 14 such conversions made before its 20th-century and 21st-century evening sales.

Most of those lots sold on a single bid (presumably purchased by the backers) and fell below the low estimate, a sign of little interest and reduced reserve levels by the sellers. Information like this is key to market participants, yet the presence of third-party guarantors would be unknown to anyone checking Christie’s website during the sale or afterward. A spokesperson said the house’s disclosure practices had not changed as a result of the New York reforms. She noted that while salesroom announcements offer the most up-to-date information on third-party guarantees, “it generally has not been our practice to retroactively update our website with these late guarantee adjustments after a sale concludes.”

Act Four: The Final Prices

Onstage: The winning bid is assumed to be the price.

Backstage: Auction houses no longer have to reveal the final price paid for a work of art.

Ever since third-party guarantees began popping up at auction, the art trade has been complaining that such transactions are pure theater—private sales executed in front of a live audience. Third-party guarantors, many argued, had the unfair advantage of knowing the reserve price. Why? Because in these cases, the irrevocable bid effectively becomes the lowest figure at which an artwork can sell, or the reserve. Guarantors also often get a financing fee for offsetting the risk of either the consignor or the auction house, if it provided an in-house guarantee. That fee amounts to a discount—sometimes in the millions of dollars—if the backer ends up buying the work.

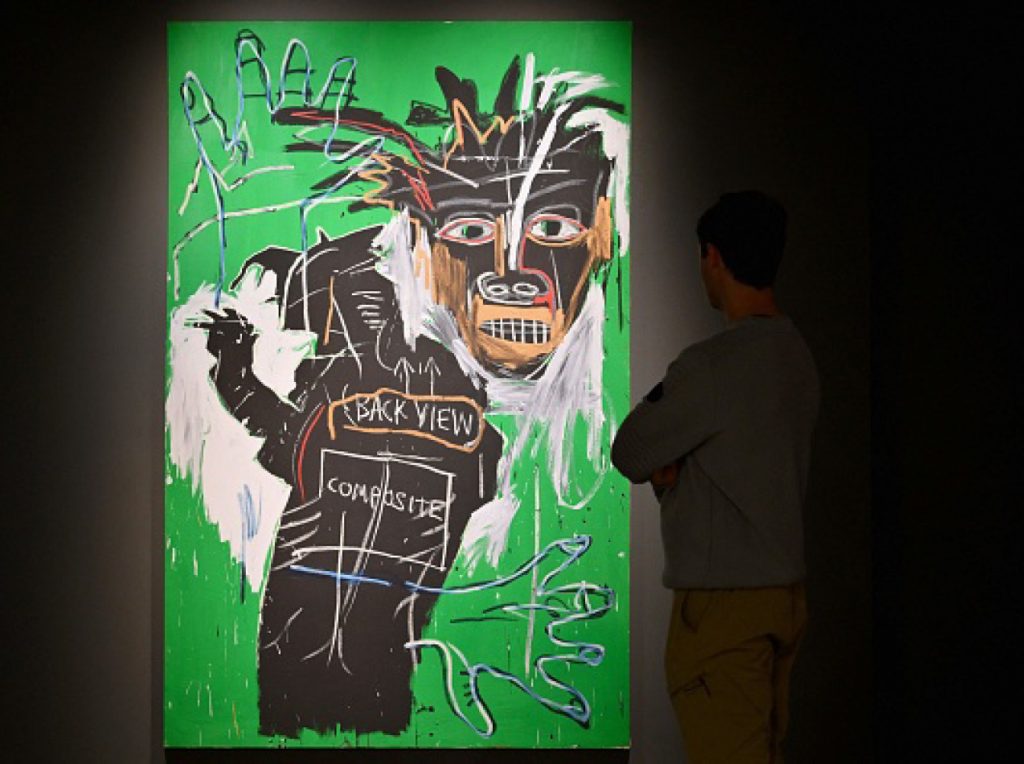

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Self-Portrait as a Heel (Part Two) (1982) sold to its third-party backer at Sotheby’s in November for $42 million. Photo by Angela Weiss/AFP via Getty Image.

In 2016, New York City mandated that auction houses record prices net of fixed fees on guaranteed lots sold to third-party guarantors. The final prices reflected the hammer price plus buyer’s premium minus the financing fee. It was a transparent, if cumbersome, process.

With no legal restrictions on that front anymore, Christie’s and Phillips decided to go back to reporting gross figures—the hammer price plus the buyer’s premium. Sotheby’s, meanwhile, still reports prices net of fees paid to third-party guarantors. This allows us to figure out, for example, that the backer of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s $42 million Self-Portrait as a Heel (Part Two) at Sotheby’s received a $3.1 million fee in November.

While Sotheby’s approach is the most transparent, the divergence among the three biggest houses has the potential to create confusion, yielding different results depending on where you shop. The fees tied to guarantees may also distort the real value of the objects in a market where auction prices serve as vital tools for assessing appraisals for and loans against comparable works, experts noted. In February, Sotheby’s announced plans to overhaul its fee structure, adding to the inconsistency across houses. “You can no longer compare apples to apples by looking at auction results,” Danziger said.

Epilogue

The houses have claimed to be committed to transparency—while doing their best to make the auction process as smooth and seamless as possible to achieve the best results for their clients. “No one is to gain from greater opacity,” said Bonnie Brennan, Christie’s president of Americas. “We all benefit from transparency in our business.”

And yet changes are being made, quietly, in small print—and in real time. Some of the moves, like the new language on reserves, are hard to spot. Others, like Sotheby’s new fee structure, are broadcast with a megaphone.

The stakes are especially high now. Worldwide fine art auction sales dropped by almost 13 percent last year, with the largest contraction at the top end, where complex financing deals often take place. Sales of art worth more than $10 million dropped by almost 40 percent in 2023. This season, many investors are sitting on the sidelines, waiting to see how the contraction plays out. Auction houses can’t afford to let negative optics alienate them further.

New clients, especially Mainland Chinese buyers, millennials, and Gen Zers, are attracted to auctions because of their perceived transparency and fairness, said Michael Plummer, who advises investors. “They also want the comfort that the price they pay is fair market because there was someone bidding against them,” he said. “If we start to undermine this faith in the system, it can go pear-shaped.”

It’s too early to know which new auction strategies and rituals will stick, what new ones are still to emerge, and which will be challenged by buyers and sellers. One thing is clear, however: the show will go on.