Art World

Art Bites: What Happened to Jesus’s Feet in Leonardo’s ‘Last Supper’?

The artist invented a new technique to paint the 1498 commission, but it didn't really work.

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history. These delightful nuggets shed light on the lives of famed artists and decode their practices, while adding new layers of intrigue to celebrated masterpieces.

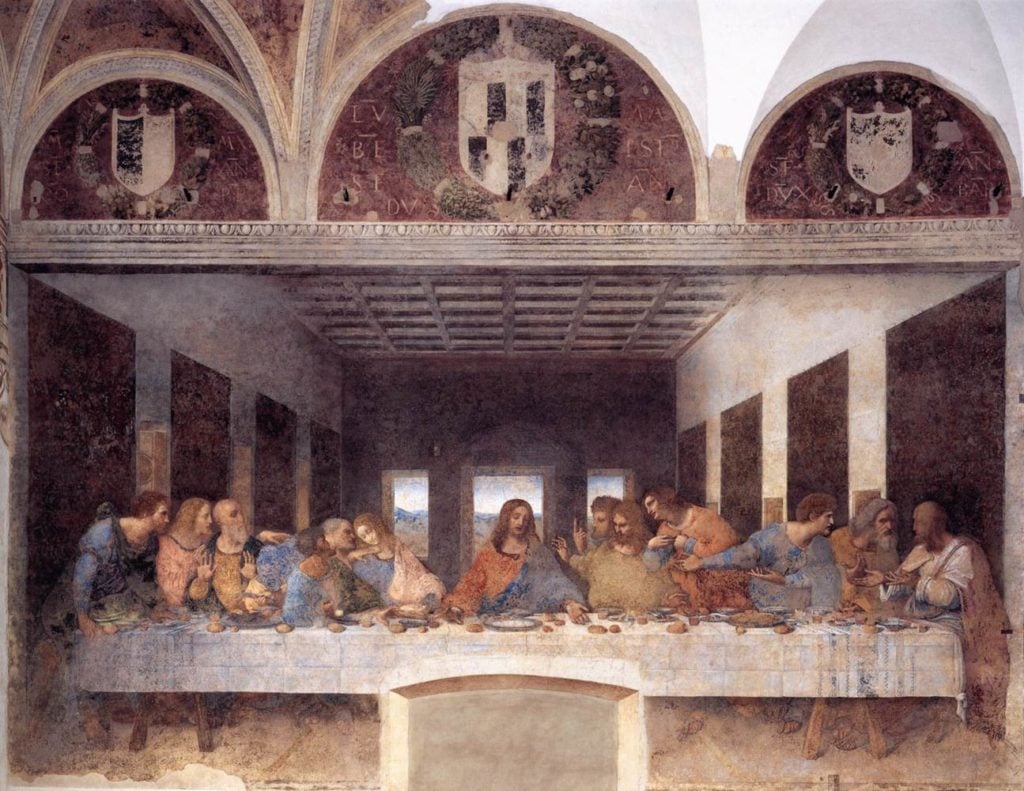

Jesus’s feet are typically depicted one of two ways in Renaissance paintings: nail-punctured and bloody, or in the process of receiving a good scrub. However, in Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper—possibly the most famous Christ painting by the period’s most famous painter—the messiah has no feet at all.

They were chopped off in 1652, along with his legs, to make space for a doorway into the refectory of Milan’s Santa Maria Delle Grazie. Aside from the practical concerns of monks seeking to improve dining room access, the willingness to destroy part of the Last Supper might have had something to do with the work’s condition.

In the painting of the 12 apostles and their fateful soirée, Leonardo demonstrates a mastery of linear perspective, human emotion, and symbolism. Less convincing was his application of a painting technique he invented for the Duke of Milan’s commission. He fixed tempera and oil to the wall, but soon after the work’s completion in 1498, paint began to flake and fall. Steam from the convent’s kitchen and soot from nearby candles hastened the deterioration.

A detail from the copy of Leonardo’s The Last Supper (c. 1515–20) attributed to Giampietrino and Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio. Courtesy of Google Arts and Culture.

“A muddle of blots,” was how Renaissance biographer Giorgio Vasari put it 60 years on. The 29-by-15-foot painting has received numerous muddled restoration efforts over the proceeding centuries, but fortunately Leonardo had capable—if opportunistic—understudies who painted copies of Last Supper on good old-fashioned canvas.

One facsimile comes courtesy of the northern Italian painter Giampietrino, a work held by London’s Royal Academy of Arts. It formed the basis for Google Arts & Culture’s 2020 digital remaster that captured the painting in ultra-high resolution, billion-pixel images.

A detail from the copy of Leonardo’s The Last Supper (c. 1515–20) attributed to Giampietrino and Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio. Courtesy of Google Arts and Culture.

And Jesus’s feet? They are sandaled and positioned in a gesture suggestive of his looming crucifixion. Other details smoothed into the digital copy include the raised finger of doubting Thomas, the salt cellar knocked over by Judas, and the man’s money purse.

Back in Milan, the doorway has been bricked over and visitors now can stand beneath the feet of Jesus and admire a restoration that lasted two decades. Though, like much else surrounding Leonardo’s Last Supper, it’s controversial.