Artists

9 Powerful Couples Who Moved Beyond the Binary of Artist and Muse

Here are romantic partnerships that have spawned creative collaborations, spanning from the the early 20th century to today's art world.

Historically, many creative couples have been celebrated within the dynamic of artist and muse. The relationship between the two has typically been that of a male artist and a female muse, which has led to an imbalance of attention on the man’s talents, even when his partner is a voracious and skilled art maker. But for many artist couples, the creative aspect of the relationship is on an equal footing, with both inspiring one another and working with a powerful synergy.

Here are some of the romantic partnerships that have set the art world alight, from the start of the 20th century to the present day.

Ugo Rondinone and John Giorno

Ugo Rondinone and John Giorno. Photo by Giasco Bertoli.

While many artistic couples collaborate on common themes, it is rare to find such a personal working relationship as that between Ugo Rondinone and the late poet and activist John Giorno. In 2017, Rondinone staged “I ♥ John Giorno” across thirteen venues in Manhattan, dedicated to his partner in the last years of his life. The exhibition featured painting, film, sound, drawing, archival presentations, and a video environment, created by Giorno and artists inspired by him. The show was an expanded love letter from Rondinone.

“In 1997, Ugo asked me if I’d take part in one of his exhibitions, after having been to one of my performances,” Giorno previously said of their initial meeting. “The idea behind his installation was pretty amazing: speakers arranged in trees, which emitted not music, but poetry. Ugo wanted it to be my words. So we talked. We drank more than we should have … And then we became lovers. It’s as simple as that. And it’s been thus for the last 18 years…”

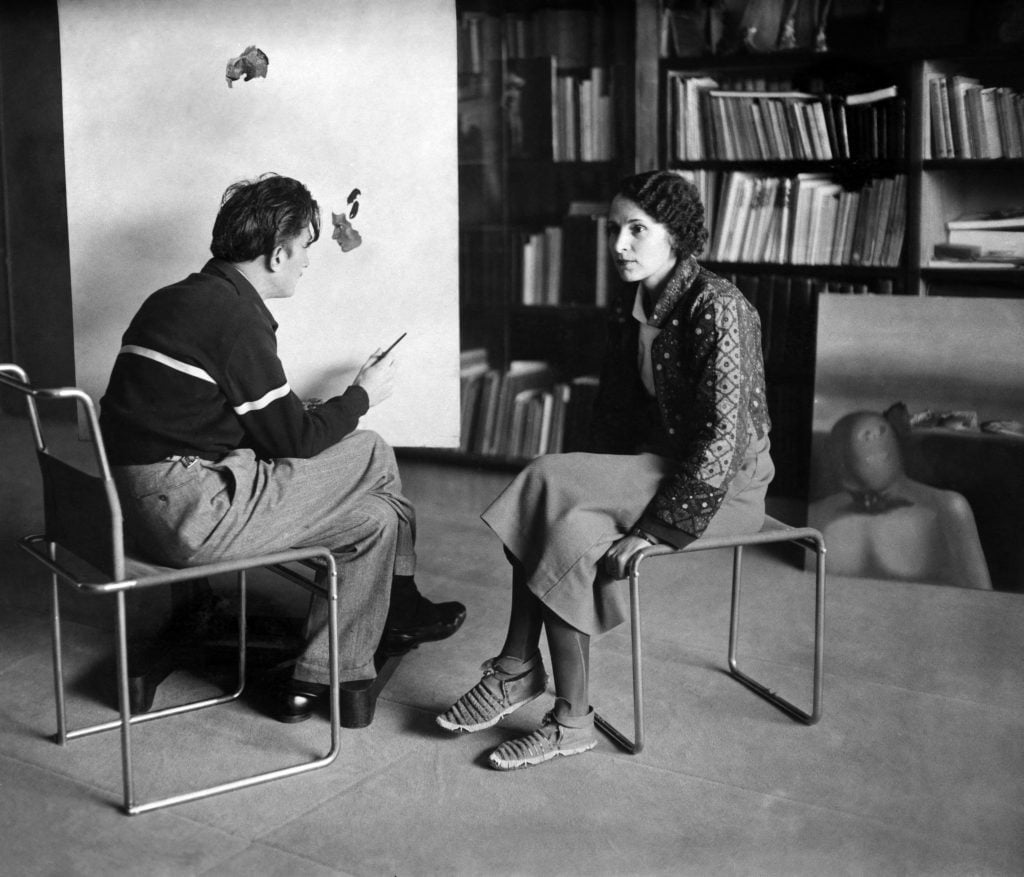

Leonora Carrington and Max Ernst

Leonora Carrington and Max Ernst. Published in Scrap Book by Roland Penrose, 1981, page 123, La Poligrafa, Barcelona.

Leonora Carrington and Max Ernst’s relationship was tumultuous, but their attraction to one another was rooted in their artistic output, with Carrington once saying, “I fell in love with Max’s paintings before I fell in love with Max.”

The two intensely accomplished artists met at a dinner party in 1937, when Carrington was 19 and Ernst was 47. The young painter ran away from home and travelled back to France with Ernst, who then left his second wife. The two painted together in their Parisian home, playing host to fellow surrealists, including Marcel Duchamp, Pablo Picasso, and Joan Miró.

During wartime, Ernst, who had escaped arrest in Europe thanks to Peggy Guggenheim, later married the famous collector. Carrington left Europe and, after spending some time with Guggenheim and Ernst in New York among a wider scene of artists, eventually made her way to Mexico, where she became a national icon.

Holly Herndon and Matt Dryhurst

Matt and Holly by Suzy Poling. Courtesy of the artist

This duo has a truly forward-looking practice, exploring the ethical dilemmas of contemporary technology. They are solo artists who regularly collaborate, with Herndon working primarily with music and Dryhurst in digital media. Together, they advocate for artist’s rights in the age of A.I. learning, tackling urgent contemporary problems through varied art forms.

Each brings a unique approach. For example, Herndon’s musical experiments have included training an A.I. “digital twin” to mimic her voice, while Dryhurst has created Saga, a digital platform that decentralizes creative content online.

For Herndon and Dryhurst, cooperation spans far beyond the reaches of their relationship. Their 2019 album “Platform” invited people all over the world to collaborate online. “When we were working on ‘Platform,’ that idea felt incredibly optimistic, especially as opposed to the main discussion at the time, which was mostly around Facebook and other centralized platforms’ control over our relationships,” Dryhurst had said of their collaboration in 2021. They have met yet another crucial issue of the moment with Spawing.ai, which helps artists opt out of A.I. to protect their intellectual and creative property from being used by machines.

Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller

Photo courtesy of the Artist and Luhring Augustine, New York

Married couple Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller began working together on ambitious, immersive installations in 1995. Their works often play with multiple senses, drawing on the viewer’s emotional response to unnerving narratives. For example, a 2007 piece presents an elaborate installation that includes a button-activated dentist chair, inspired by 1914 short story by Franz Kafka that features a similar piece of furniture. They have previously described their pieces as “hybrids between theatre, music, and the visual arts.”

Throughout their projects, the pair share roles, with Miller often taking on the more technical aspects and Cardiff the conceptual, although it is not always so clear cut. “I have a tendency to want to talk about it more, and George wants to build it right away and see how it works,” Cardiff has previously said. “I think we’re a very good combination of different talents that go together, and we generally agree on what we like.”

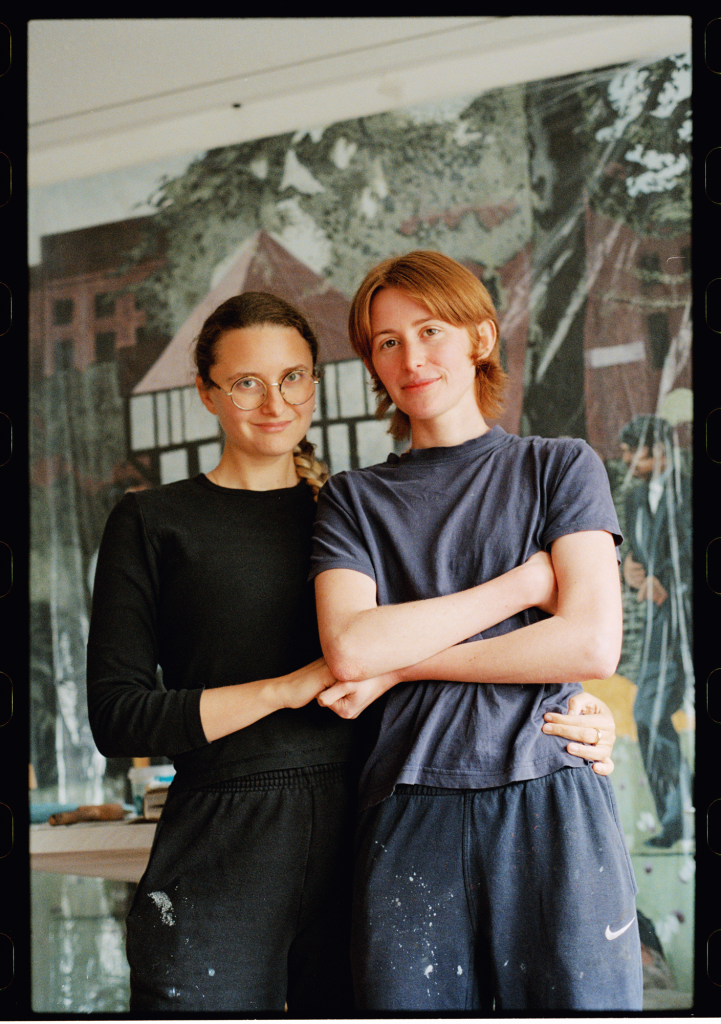

Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings

The artists Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings. Photo: Angel Li.

Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings began collaborating on digital imagery and performance in 2013, after meeting on a New York workshop they had both been awarded while studying at Goldsmiths. Since then, their joint practice has tackled the dominance of gay bars set up for male visitors; the British history of the feminist movement in the political right; and the power dynamics inherent in public space.

Their work is often surprising and diverse in its expression, as they move with ease between pop-up live events, energetic paintings, and detailed etchings. “One of our first rules was to lose your personal ego and sense of ownership over your own creations,” Quinlan has previously said about their collaborative working style. “When we first started our practice together, we were making installations, films, and performance art. Those mediums that are more naturally suited to collaboration and teamwork, such as filmmaking, built up our tolerance and confidence for collaboration.”

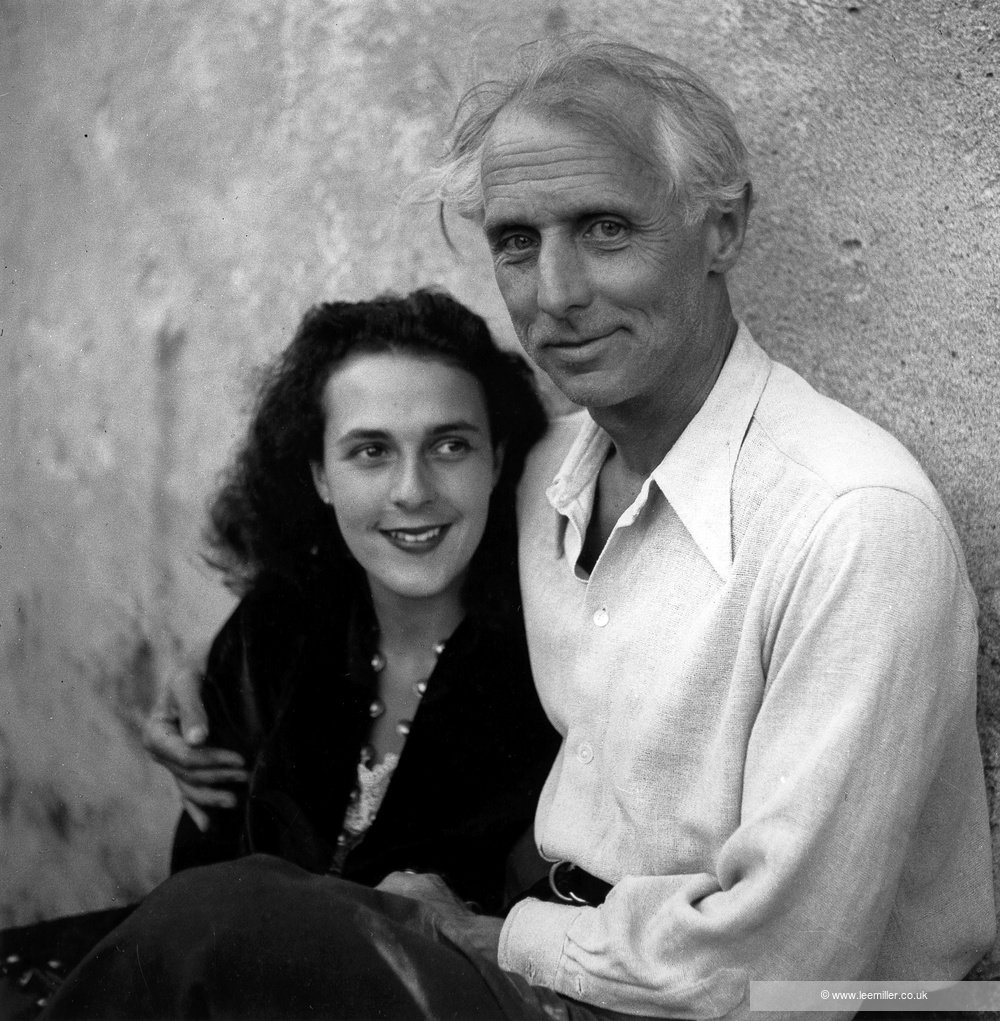

N. E. Thing Co.

Iain, Ingrid, and daughter Erian Baxter. Courtesy of the Artist

N. E. Thing Co. was founded in 1966 by Iain and Ingrid Baxter, acting as an art collective in Vancouver, Canada, until 1978. The pair set up the collective in the format of a commercial enterprise, with numerous departments, a traditional corporate structure, and official titles for the chief officers. In their time running N. E. Thing Co., the then-married couple engaged in a series of unconventional conceptual gestures, such as opening a restaurant, and eating half a meal before freezing it to finish the next year.

After they divorced, the archive fell under the control of Iain Baxter. In a 2014 interview, Ingrid Baxter said one goal of the highly unusual project was to deal with gender bias in the art world. “I would say that was part of our motivation—not mine, not his, but ours. When Iain and I worked together, the ideas happened between our two brains,” she once said. “To Iain’s credit, he made sure that writers and curators understood my contribution, at least back then.”

Petra Cortright and Marc Horowitz

Petra Cortright and Marc Horowitz at home in L.A. Courtesy of Jennelle Fong.

Painters Petra Cortright and Marc Horowitz met in a hot tub at a mutual friend’s house. “I was getting pretty tanked up,” said Horowitz. “Then this girl got in the hot tub and I was just gobsmacked. I was like, ‘Who is this?’”

They now both work in studios connected to their house in Los Angeles, with Horowitz working in a hands-on manner with paint; Cortright creates her paintings primarily through the computer.

While they have separate practices and approaches, there is a sense of cross-pollination between them, with Cortright sometimes photographing the textures of Horowitz’s underpaintings for inspiration and both sharing books back and forth as inspiration. They have also previously collaborated on a Stella McCartney video and a 2018 joint show at BANK Gallery in Shanghai, with 34 works exploring their complimentary but decidedly individual styles.

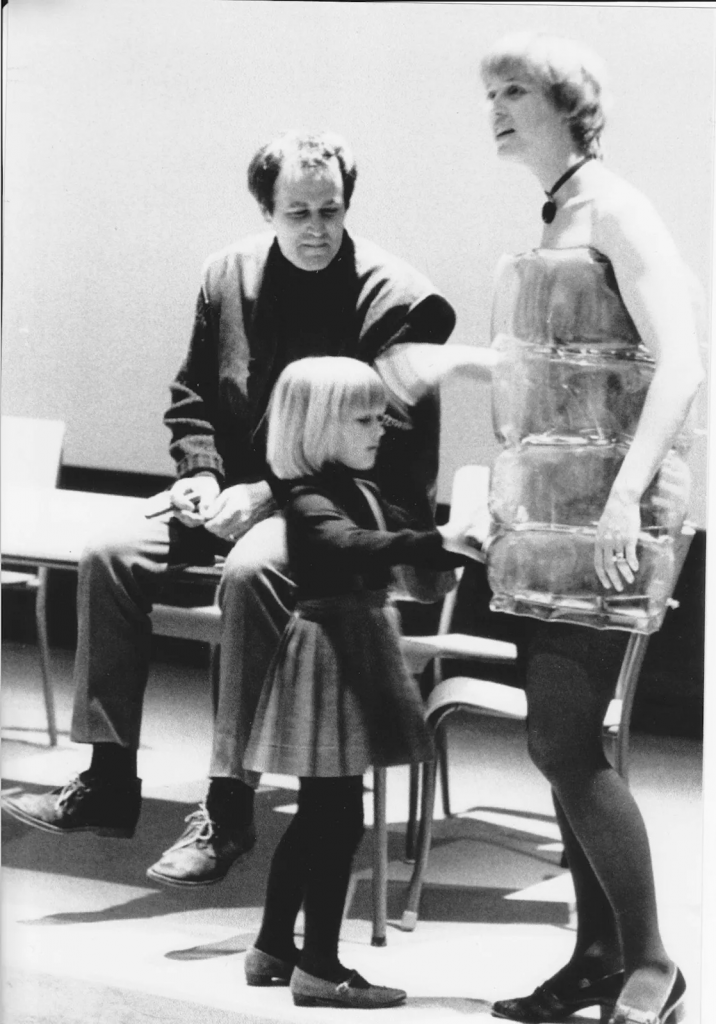

Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely

The Swiss painter Jean Tinguely and Nikki De Saint Phalle. (Photo by Monique JACOT/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Both giants in their field, sculptors Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely were in a romantic and artistic relationship for over three decades. They created major collaborative works such as the Stravinsky Fountain, which is housed beside the Georges Pompidou Center in Paris, as well as “Le Paradis Fantastique,” a joyful collection of works by both artists that now sits outside the Moderna Museet in Stockholm.

Tinguely’s kinetic sculptures were formed from industrial machinery parts, while de Saint Phalle’s explored the female body in celebratory, totemic form. Both were committed to their individual identities as artists, though they often helped each other make work. “Niki’s ego was clearly oversized and so was Jean’s, so they could relate,” said de Saint Phalle’s granddaughter Bloum Cárdenas when the Tinguely Museum staged “Niki and Jean: Art and Love” in 2006. “Niki was beautiful and magnetic and Jean was explosive, a real macho, but there was true communication.”

Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore

Claude Cahun (Lucy Schwob), Marcel Moore (Suzanne Malherbe). Untitled, 1925. Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Lucy Schwob, working in the first half of the 20th century under the pseudonym Claude Cahun, has been widely celebrated for her boundary pushing portraits which challenge gender binaries. It is believed that her partner—Marcel Moore (the pseudonym of Suzanne Malherbe) who is frequently credited as photographer—was an integral part of the playful creative process, with both artists inputting to the expressive compositions and costumes worn by Cahun.

They met in 1909, and both compared the moment of finding each other with lightning striking. Cahun’s father married Moore’s mother ten years later, casting the artists as both step siblings and romantic partners. The two worked together in their apartment in Paris in the 1920s and then fled to Jersey at the outbreak of war. Both were arrested for their two-person campaign that spread disinformation aimed to confuse German communications.