Petra Cortright makes pretty paintings—an irreverent undertaking in an art world that is more than ever aligning itself with the issues of the day (to varying degrees of effect). The U.S.-born artist doesn’t concern herself with that trend, just as she doesn’t concern herself with critics who can’t understand how she makes paintings without paint. She has long been interested in the internet, and her paintings warp and distort whatever she lands on there into beautiful, if unfamiliar, imagery.

In the early 2010s, Cortright became known among a cohort of millennial digital post-internet artists for her short statement video works that innovated and confounded the notion of selfies and other forms of self-presentation online. And her work continues to find relevance today: Just last year, in a flurry of pandemic buying, MoMA in New York acquired Cortright’s prescient early work VVEBCAM (2007), which features the artist staring vacantly at the screen as little JPEGs flicker across. This year, she will head to Saudi Arabia to take part in collector Pierre Sigg’s newly established artist residency.

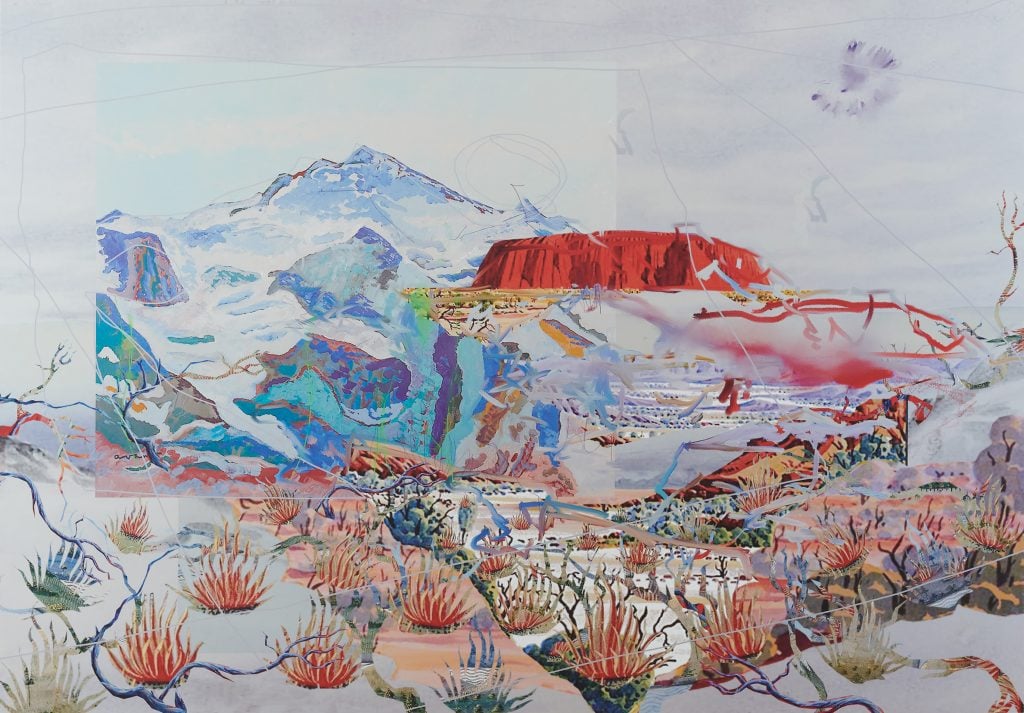

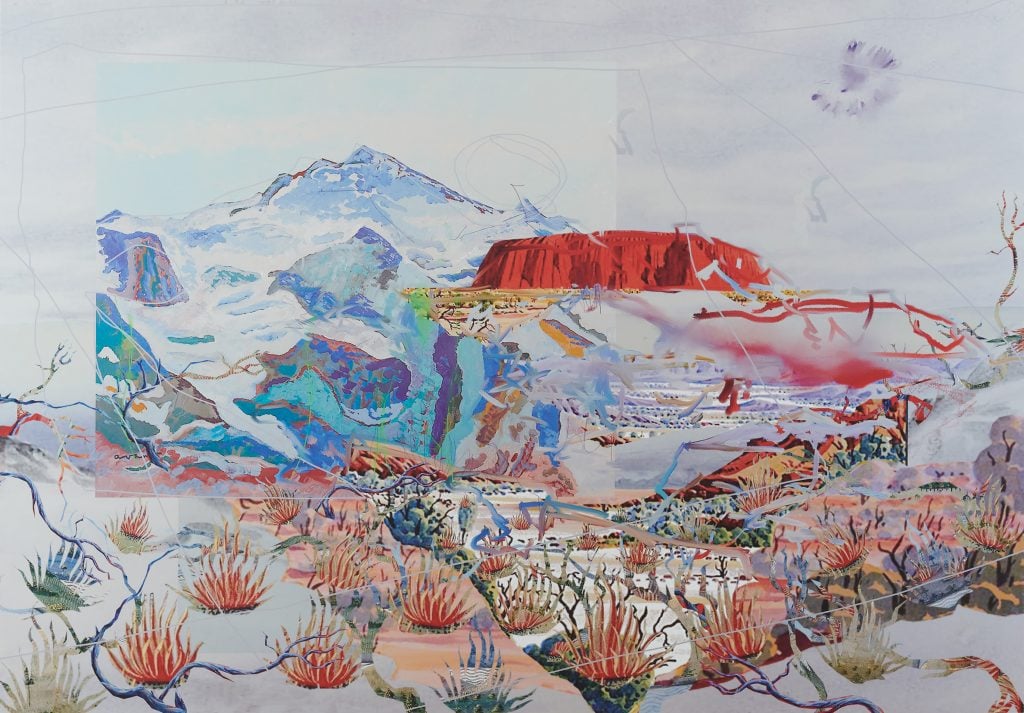

In painting, her visual language is not low-res portraiture, but rather vibrant and detailed landscapes on cold aluminum that seem to radiate light, which she makes by overlaying and distorting pictures she finds on the Internet.

Artnet News spoke with the artist about how she adapts to a changing Internet, growing into a new stage of her life and career, and why she likes to leave politics outside the studio door.

Installation view of Petra Cortright’s show “Baleaf Gys Akademiks Maamgic Brokig” on view until February 5, 2022, at Société, Berlin. Courtesy Société, Berlin.

Can you tell me a bit about your show on view in Berlin right now at Société?

The file is built in Photoshop—a whole series or a whole show comes from one file. The source images are from the internet or from my cell phone and the images are broken apart or broken down. Colors from the pixels can be extracted for paint strokes. The brush strokes are made from Wacom tablet, so it is by my hand. You can make the brushes from scratch, so what that means is that you can save a certain set of parameters and you can control the number of bristles in the brush, the angle, and the percentage of water in the brush. All these things we’re talking about is about controlling pixels, but it is hyper-realistic to painting. I have like a collection of over a decade of saved brush packs that I’ve collected for years now.

Each element of the painting is completely editable and malleable, so every little piece that you see can be changed. Many files are saved, many versions are saved, and then I save as I go. I’ll go back later and select the ones that are my favorites and those are sent to the printer to be produced into a physical work. The mood of the file dictates the substrate a little bit. Certain files will read better on aluminum or certain ones will read better on linen. The number of that just depends on how big the gallery is.

When you see your work as images online, it could appear as if it’s painted on paper or canvas. I wonder, do you feel like your work ever is misread?

Yeah, it’s something that I’ve been explaining for a long time and I think I’ll have to keep explaining it for a very long time. The issue is that I’m a painter, but I don’t use paint, so it confuses people. I’m not trying to confuse people but it does. How do you make a painting without paint? What makes a painting a painting? I always wanted to be a painter and I think I have a painter’s brain but I don’t have the patience for the process or the materials. Plus, I never had the money to invest into that process, either. There is somewhat of a barrier of entry into that, and I have always just felt so clever and powerful when I use a computer. I can work quickly and I can make so many files—I think that’s a holy grail situation for an artist, when you are able to produce quickly every idea that you want to make, with no holds barred. Just the freedom in that is something that I really value, so I don’t even know how I would not work digitally. When I choose to produce a physical piece, that’s when money gets involved. It’s quite expensive to make nice physical things.

Petra Cortright 1983 oldsmobile cutlass supreme_688(I) Hunter/Killer animorphs Nickelodeon (2021). On view until February 5, 2022 at Société. Courtesy Société, Berlin.

What sets you apart from a lot of artists, in my opinion, is your disinterest in trying to be on the right side of issues. You always tried to not bring ethics into your work and keep art separate. How have you been thinking about this lately?

The art world almost has a gun to people’s heads in the current climate, telling them to make work that is political, social, or about someone’s identity. Art is so much bigger than that. I’ve always separated art from the art world and from the art market. It’s something that’s really important for me to be able to do because art would otherwise be ruined for me. Art in a very pure, abstract form is worth fighting for. The art world is a social construct: At its best, it can be a supportive community of people and, at its worst, it has almost nothing to do with art and it’s just a social thing. The art market is a financial construct that’s barely real and completely laughable because it’s just so dark. I couldn’t sleep at the end of the day if I felt hypocritical about my work or if I was trying to say that the work was doing something or helping people in a way that it just wasn’t.

It’s very simple for me: Art in general is very meaningful to me and I feel like I am a defender of beauty and simplicity. In that sense, I have no problem letting go of the work, selling it, or having it be in the art world, because that meaning is already there for me, and it’s already very separate. Making a living of art is a huge surprise and privilege. I failed at almost everything else I’ve tried to do in my life, so I feel very lucky. But trying to mix that in with ethical questions gets very complicated very quickly. I have no problem selling work or making a living off of it, because I want to have a stable and good life, and I’m not going to apologize for that or say that I don’t want that. Because I definitely do.

It sounds like you have your own ethics around being honest about why you are making art and what it means to you, but it just does not align with the dominant discourse.

Art can help things in a very abstract way, but if you really wanted to help people, you could become a social worker. There are other jobs that you could do that would make 1,000 times more of an impact. My intention has always been to make work for myself. I seem to be non-functional in other endeavors that I’ve attempted in life. If there is a byproduct of other people enjoying the work and they want to buy it, then everyone wins.

Petra Cortright’s vvebkam (2007) “Body Snatchers (The Church)” at the Church of San Giuseppe, Polignano a Mare (April 12 – June 20, 2021).

The works on view at Société seem to draw on the colors of the forest fires. You are based in California. Is climate change something you were thinking about actively while making the works? How has life been during these past couple years with these annual disasters?

I don’t think any of the work I make is overtly a statement, but I think there are subtle things that leak, which happens when you are producing abstract visuals. The anxiety of living in the Western U.S. is ever-present. There’s anxiety about fires and lack of water. Fires affect the light here and the air quality and there are certain times when it’s impossible not to think about it. It definitely bleeds in, especially if I’m painting landscapes. I am also working with source images from the American West. I’m really interested in that aesthetic right now for many reasons. I am interested in the Wild West and the idea of America, freedom, and what that means and how that has changed so much in the last couple years. The show at Société was also loosely heaven and hell inspired, which also goes along with the idea of America and all the polarizing aspects of life here.

Right. It feels like you’re surrounded on all sides: physically, mentally, virtually.

Yeah, but it’s fine. My quality of life is quite good. There are these constructs in people’s minds now. You can be as miserable as you want to be for many reasons, whether it’s politics or environmental issues, but at the end of the day, it can be somewhat a choice whether to be miserable.

How has a transforming internet changed the way you work?

I definitely use more of my own photos now in my paintings because it became harder to find interesting source material that wasn’t affected by algorithms, which make things boring. They’re just trying to push products for sale. I use Bing image search, which will bring up Blogspot images so you can sometimes get more interesting results. The way that I engage with the internet is very different now than it was like 15 years ago for many reasons. There are reasons that are out of my control, and then also I am a different person than I was 15 years ago, too.

Pink_Para_1stchoice Time’s square Electronic Billboards, New York, 2019.

Do you feel more attached to a certain era of the Internet?

I’m mostly interested in what I can make today. I’ve never really been the type of artist that thinks a lot about the future. I do get nostalgic for the past, but I actively try to work against that because it’s not productive. We can’t go back to the internet that was, and it creates so much suffering to live outside of reality like that. I try to avoid that level of suffering in my life. I’ve just made peace with the fact that the only thing that I can make is what I can make today. Naturally, my interests will keep changing and evolving, and I feel like the future will sort itself out without me thinking about it or worrying about it today.

A big topic in art presently is NFTs.

I’ve made a lot of them simply because the work that I’m already making slots into it so effortlessly, even the file sizes. The videos that I’ve always made have been quite a low file size. I try to be brave and keep engaging. I don’t like thinking about what is the right thing to do. As much as possible, I try to experiment and engage, which I think is more productive and interesting at the end of the day.

On your website, requests for purchases are directed to your studio email. Most artists at your career stage refer a prospective buyer to their primary gallery. What is your relationship to your galleries?

I probably work a little differently than most people—there is central control with my studio. I work with an art dealer in L.A., the infamous Stefan Simchowitz. I have good relationships with all the galleries. The studio filters requests and it just gets divvied up somewhat geographically. If the request is coming in from Europe, it makes sense for a European gallery to handle it. I just try to do things logically and simply. I make a lot more work than I can show or that can be in the market at any given point in time. There’s not really like a supply issue when it comes to working with many galleries.

3_beutyfol girls xerox desert rose at Doota Plaza, Seoul (2018) by Petra Cortright (2018). Courtesy of Artist and Sketchedspace

What are the benefits of having several galleries, plus one art dealer, at this point in your career?

All my galleries are mid-career galleries. None of them are blue-chip, and that is fine. That seems like a whole new set of politics and social aspects. I don’t know how interested I am in that. I’m just very happy with how things are now. Everything is very functional, and it’s nice to work with people that I really like. I just like to work with people that I also enjoy having dinner with. It’s a nicer way to operate.

You are a mother now. How do you navigate motherhood as an artist, given your disinterest in identity tags?

I’m very protective of my kid. There are people who know that I have a kid, but he’s not really on social media or anything like that. I have very strong feelings about children and social media. I want to give him the gift of privacy as much as I can. Every once in a blue moon, I’ll do a close friends post—but I try to keep him protected as much as I can from the evil art world.

I don’t really trust other people’s perceptions of my life. That someone would think that it’s like a weakness, which it is not. This probably also deals with the way that I use the Internet now. Fifteen years ago, I shared a lot of personal information online. Now, I really don’t share that many personal details about my life.

CLINTON+CIGAR CODES OF X-MEN VS. STREET FIGHTER_Commodore 1541 (2021). Courtesy Société, Berlin.

Have you cleaned up your old stuff on the internet at all?

I don’t delete anything from the internet. I’ve actually made a point of it. It was something that I decided to do a long time ago: if you’re going to put this out there and if you’re going to engage with the world in this way then you should live with the consequences of that. There is information from half my life decaying and rotting around online. If people knew where to go looking for it they could uncover some cringe-y embarrassing things. My Live Journal is up. But there’s so much information that it is just kind of lost.

How has becoming a mother changed your work flow as an artist?

I have a son. It definitely changed things. I don’t get to work in an unlimited way like I used to. I have to wait sometimes if I have an idea, and then it takes a little bit longer to find the time to get it done. It’s also an energy thing, like just being more tired. I used to work in really long 10- or 12-hour sessions on the computer. I cannot do that anymore. I had to learn how to find a way to get something done by chipping away at something for like 45 minutes and taking a break and coming back to it. It is probably good for me. I’ve always had this fear, like with any big life change that I’ll never be able to make work again, or I’ll never be able to make work how I did, and then that’s never the case. Because I have all my files, I have proof of what I’ve done before and can compare it with what I’m doing now. It’s even more complex than before, in my opinion. So, it’s a good thing.