Art World

Two Baltimore Museum Trustees Resign and Donors Rescind $50 Million in Gifts as the Institution Prepares to Sell Off Blue-Chip Art

Artists Amy Sherald and Adam Pendleton have stepped down from the board amid the controversy.

Artists Amy Sherald and Adam Pendleton have stepped down from the board amid the controversy.

Sarah Cascone

The controversy over planned sales of a trio of paintings by Brice Marden, Clyfford Still, and Andy Warhol is escalating at the Baltimore Museum of Art, where two former board chairmen say the deaccessioning and recent leadership direction have prompted them to rescind $50 million in pledged donations.

Director Christopher Bedford plans to fund diversity initiatives at the museum using an expected $65 million from the sale of the blue-chip artworks.

Meanwhile, two artist trustees, Amy Sherald and Adam Pendleton, have also resigned, though they did not specifically weigh in on the deaccessioning controversy in their letters.

Charles Newhall III resigned as an honorary board trustee on Friday, announcing that he and Stiles Colwill no longer planned to follow through on gifts of $30 million and $20 million, respectively. Colwill also resigned as honorary trustee at the beginning of the board’s October 1 meeting, during which the upcoming sale was approved. Of the 37 voting members, two opposed deaccessioning the Still and Warhol, and one the Marden. (As honorary trustees, Colwill and Newhall did not hold voting power.)

“I do not agree with Chris Bedford’s vision of rewriting the canon of art history by rectifying the wrongs of the past. I certainly do not believe that one sells masterpieces to fund diversity,” wrote Newhall.

The Baltimore Museum of Art. Photo by ERIC BARADAT/AFP via Getty Images.

Bedford and Clair Zamoiski Segal, the museum’s board chair, say that they were never counting on the donations, and therefore the deaccessioning push has not cost them any funding.

“The $50 million number circulating is a reference to assertions that Charles Newhall verbally pledged $30 million and Stiles Colwill verbally pledged $20 million to the museum. These intended pledges have not been recorded with the museum as gifts and are not part of the museum’s current budgeting,” they said in a joint statement.

Newhall claims his gift was part of the museum’s 2014 100th anniversary fundraising campaign, “In a New Light.”

“We never put anything in writing, but I ran that campaign for five years. I’m sure it’s in the minutes of the various board meetings,” Newhall told Washington Post. “That’s what they are doing about everything. They are denying everything. They lie.”

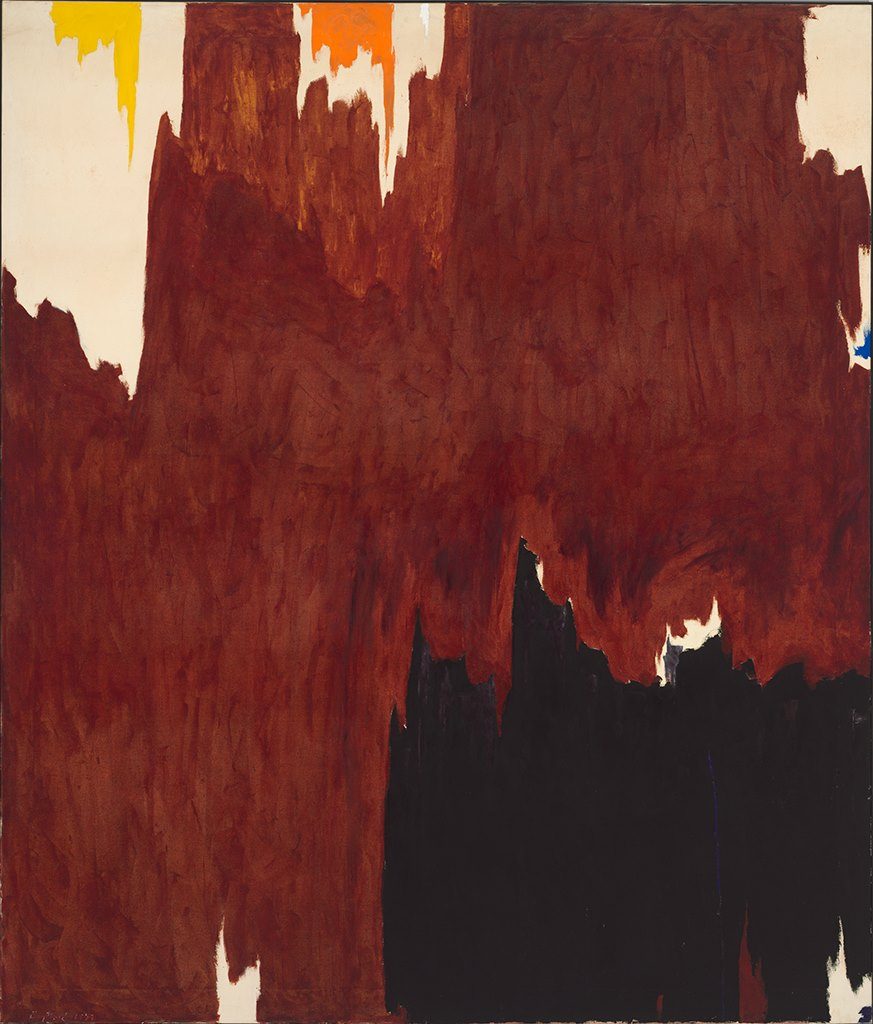

Clyfford Still, 1957-G (1957). City and county of Denver, courtesy Clyfford Still Museum/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Bedford, who in 2018 sold seven works in the museum’s collection by white male artists to raise funds to purchase work by women and artists of color, has been an outspoken proponent of diversification.

“Everyone is entitled to their opinion, of course, but to me, any opposition to that effort—which is so many decades overdue—is itself an investment in a system of operating institutions that is very deeply centered in white power and white privilege,” he told the Baltimore Sun. “I have absolutely no doubt that institutions like ours will be on the right side of history when history is written.”

Newhall also complained in his letter that Bedford had been “stacking the board with artists that he promotes, and the BMA has bought paintings from. This appears to be a serious conflict of interest.”

The comment seems to refer to artist Amy Sherald, whose work joined the collection thanks to the proceeds of the 2018 deaccessioning. Sherald took issue with Newhall’s comments and responded: “This is a high mark of audacity to assume that I was nominated only to be used as a pawn for Christopher Bedford’s gain.”

Amy Sherald’s Planes, rockets, and the spaces in between (2018). Courtesy of the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Meanwhile, Adam Pendleton noted that he felt “blindsided by recent controversies,” and added “I have my opinions about the recent and ongoing proceedings but do not feel as though I am in a position to weigh in.”

“Adam Pendleton and Amy Sherald determined that they could not fully participate in board activities due to other commitments and have resigned,” a board spokesperson told ARTnews. “We are grateful for the time they invested and for the perspectives and ideas that they brought to the BMA.”

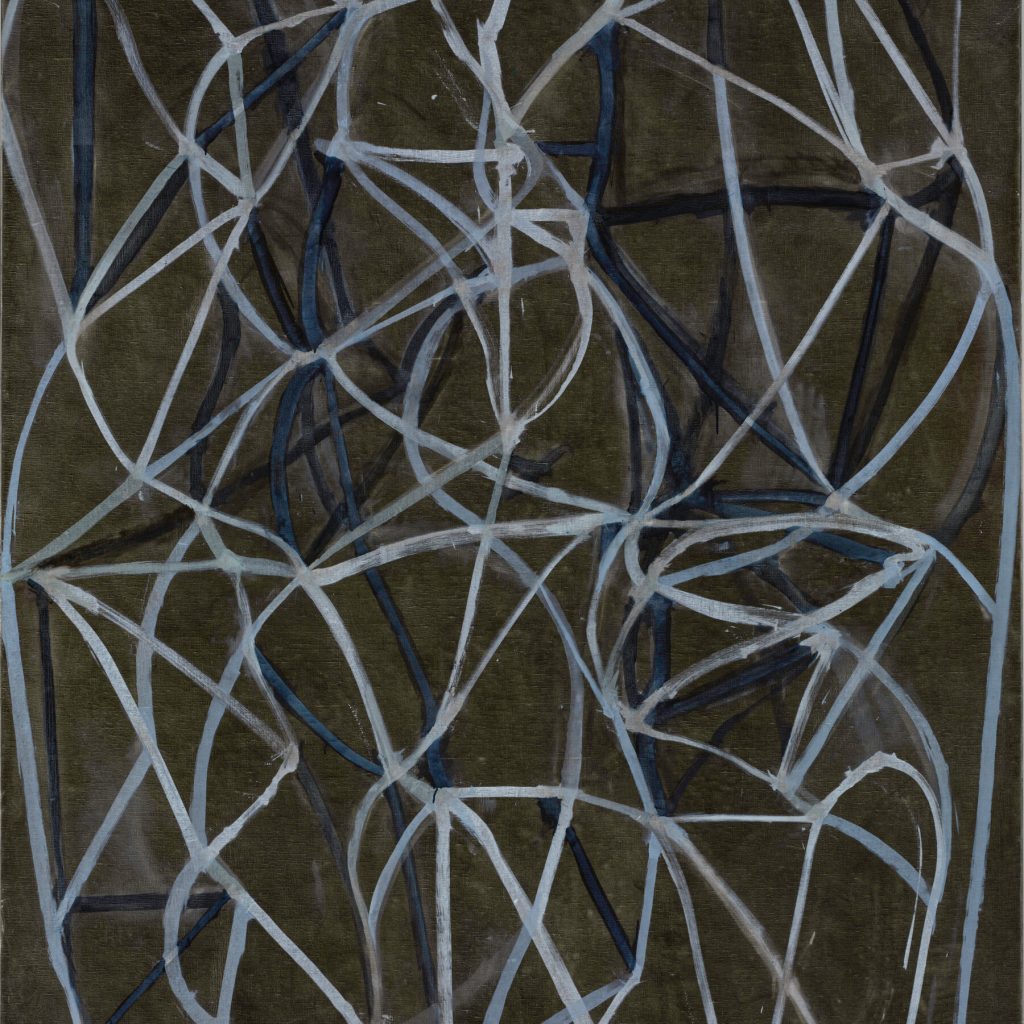

The museum plans to sell Marden’s 3 (1987–88) and Still’s 1957-G (1957) at Sotheby’s on Wednesday, for an estimated $10 million to $15 million and $12 million to $18 million, respectively. Warhol’s The Last Supper (1986) is being sold privately by the auction house, presumably for about $40 million.

Brice Marden, 3 (1987–88). Courtesy of Brice Marden/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The museum plans to use $10 million of the proceeds for acquisitions, plus $1 million to fund diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion programs. The other $54 million will be used to create an endowment that will provide $2 million to $2.5 million for those efforts each year. The museum also plans to increase staff salaries in a push for pay equity, offer free admission to special exhibits, and expand its evening hours.

A number of prominent museum supporters, including former board chairwoman Constance R. Caplan have moved to block the sale. A letter to Maryland attorney general Brian Frosh and secretary of state John C. Wobensmith called on authorities to investigate, alleging that the deaccessioning represents a breach of the public trust and a violation of Association of Art Museum Directors guidelines.

Bedford characterized the letter as a “petition signed exclusively—almost exclusively—by a very privileged elite.” (So far, 137 people have signed the letter posted to Change.org.)

The AAMD relaxed its deaccessioning guidelines in April to help institutions weather the financial hardships caused by this year’s closures. The Baltimore Museum, which is secure financially, is taking advantage of the rare opportunity to use deaccessioning funds, normally restricted to acquisitions, for operations costs.

The Still painting is one of only four gifts to museums that the artist ever made, and the only painting by the artist, who lived in Maryland for close to two decades, in the Baltimore Museum’s collection. The Warhol Last Supper is the most significant work by the Pop artist owned by the museum, and it does not own any other works by Marden.

Andy Warhol, The Last Supper (1986). © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image courtesy the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Arnold Lehman, who was director of the Baltimore Museum when the Warhol work was purchased, still considers it an important acquisition. “We got a lot of heat for buying the picture. Very few people were collecting the later work,” he told TAN. But Warhol dealer Leo Castelli “stopped me on the street and said, ‘Arnold, you just bought a masterpiece.’”

Segal, the museum’s board chair, has spoken out in defense the planned sale. “There is nothing short-sighted nor nefarious about deaccessioning,” she wrote in an open letter to the press. “It is a regular practice, undertaken by every art museum in the United States. Assertions otherwise are simply a means of inflaming controversy and serve only to maintain the status quo of museums as repositories of riches serving the elite alone.”

The Baltimore Museum of Art. Photo Mitro Hood.

“We’re actually being told by the ruling class that what we’re doing is not acceptable when what we are trying to do is advance a new and more just future for the museum,” Bedford told the Art Newspaper,

This is “extraordinarily divisive and destructive rhetoric,” countered former museum trustee Laurence Eisenstein in a letter to the board written this weekend and shared by art critic Tyler Green on Twitter. “Those of us opposed to the current deaccessions celebrate these goals of diversity, equity, and inclusion. But we believe that we can achieve these goals more fully by working together than by selling important and irreplaceable assets in the BMA’s collection.”

Eisenstein is hopeful the sale can still be stopped. “We’re still pressing the board that they should reconsider their decision,” he told the Post. “We’re continuing to press and present evidence to the attorney general’s office in the hope that they will intervene.”