It’s rare for an announcement about traditionally dry museum policy to generate international press attention in outlets as diverse as the Guardian and the Drudge Report. But the Baltimore Museum of Art‘s decision to sell off seven works by white male artists to create a war chest to fund acquisitions of art by women and artists of color drove a traditionally hermetic discussion about museum practices into the mainstream.

Now, the museum’s closely watched decision is beginning to bear fruit. The Baltimore institution is announcing today the first round of acquisitions purchased in full or in part with the more than $7.5 million generated from its sale of works by Andy Warhol, Franz Kline, and other 20th-century masters at Sotheby’s in May.

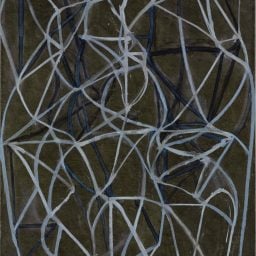

The new additions to the museum’s collection include Jack Whitten’s monumental mosaic 9.11.01 (2006), a response to 9/11 that incorporates ash and molten materials from the site of the tragedy. The Baltimore Museum’s director Christopher Bedford describes the work, which Whitten created over the course of five years after witnessing the attack on the World Trade Center from his studio, as “the most significant acquisition I’ll ever make for a museum.”

Jack Whitten’s 9.11.01 (2006). Courtesy of the Baltimore Museum of Art.

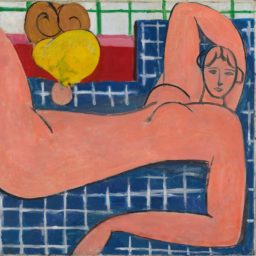

He thinks so much of the work that he predicts that in 100 years, it will regarded as highly as Matisse’s Blue Nude (1907), which is currently considered to be the crown jewel of the BMA’s collection. Bedford says he has been trying to acquire it for more than a decade, but Whitten only agreed to part with it shortly before he died, when the museum was planning a retrospective of his sculpture.

The BMA also bought Amy Sherald’s Planes, rockets, and the spaces in between (2018), the first work she painted after completing her wildly popular official portrait of Michelle Obama, and Isaac Julien’s Baltimore (2003), a three-screen video installation that follows a cyborg-like woman and an older man as they navigate the city’s streets and museums. The edition was sold out, according to Bedford, but Julien agreed to make his artist proof available so that the museum could acquire it.

As part of this round of purchases, the BMA also acquired works by Wangechi Mutu, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, and the duo Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley. (Sixteen additional gifts or purchases not acquired with the auction proceeds include a 2017 mixed media painting by Njideka Akunyili Crosby and a 2018 geometric painting by Odili Donald Odita.)

Bedford says that the museum’s acquisitions committee voted unanimously in favor of every object proposed. “It felt, to me, moving and deeply historic,” he tells artnet News.

All told, the sale of the seven works—five of which were sold at auction last month and two of which are in the process of being sold privately—will generate “substantially north of $10 million,” according to the director.

(If that math seems slightly off, given that the hammer price generated by the works sold at auction was $7.93 million, consider it an object lesson in the art market’s machinations. Bedford will say only that “the publicly reported hammer price does not always reflect the deal that was struck between the consignor and the auction house.” The BMA works did carry a financial guarantee, which makes it possible that the museum negotiated a higher price than the final hammer price in advance of the sale.)

Still from Isaac Julien’s Baltimore (2003). Courtesy of the Baltimore Museum of Art.

The end result is that the BMA has availed itself of a significant sum that will continue to reshape its collection for years to come. Indeed, Bedford says the latest round of acquisitions represents less than 10 percent of its total war chest.

All told, the money—some of which will be put into a dedicated endowment for contemporary art—”more than doubles our capacity to buy art annually and in perpetuity,” he says. A separate chunk of the total, generated from the sale of two works by Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg, will be spent “quite rapidly” over the next one to three years. In other words, visitors will begin to see even more significant changes to the collection soon.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s 8am Cadiz (2017). Courtesy of the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Asked why he thinks the museum’s plans generated such broad interest (and debate), Bedford says the plainspoken way the museum articulated its plans “was sensational enough that it pushed into a mainstream discourse” about representation and who gets to shape history.

“If we had just been selling a Franz Kline painting to buy a better one, that’s not that interesting,” he says. “But if you are selling a Franz Kline painting and the statement is being made that there are gaps in your collection created by conscious and unconscious prejudice, then you cross over into mainstream culture.”

For Bedford, this round of acquisitions is just the beginning. He plans to ask curators in other departments to apply a similar lens to the collections they oversee.

“I believe that our interest in equity, diversity, and research-based justice in collecting and presenting history is something that has to move through all departments at the museum,” he says. The American art division, for example, may deaccession some items in order to fund the acquisition of other work by Native American and African American artists—all with an eye to more faithfully telling “an equitable and true history of art.”

Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley’s Gaudy Night (2017). Courtesy of the Baltimore Museum of Art.

“You can’t stop now,” Bedford says. “You have to acknowledge that you will never, at least in our lifetime, get to true equity within the museum. But I think there is virtue in continuing to push for it relentlessly.”