Earlier this month, the Baltimore Museum of Art made headlines when it announced its intention to sell a trio of works worth around $65 million to raise funds for a new equity initiative. Now, a group of 23 museum supporters is calling on the government to investigate and put a stop to the planned deaccessioning.

In a strongly worded six-page letter to Maryland attorney general Brian Frosh and secretary of state John C. Wobensmith, signatories including former BMA board chairwoman Constance R. Caplan allege that the sale agreement with Sotheby’s is plagued with “irregularities and potential conflicts of interest” and should not be allowed to proceed.

Both the Maryland attorney general’s office and the secretary of state’s office declined to comment to Artnet News.

The seeds for the sell-off were planted when the Association of Art Museum Directors, a professional organization for North American museums, relaxed its deaccessioning guidelines in April, allowing institutions hard hit by this year’s extended closures to use the proceeds from art sales, normally restricted to the purchase of more art, for the much more broadly defined purpose of “direct care of the collection.”

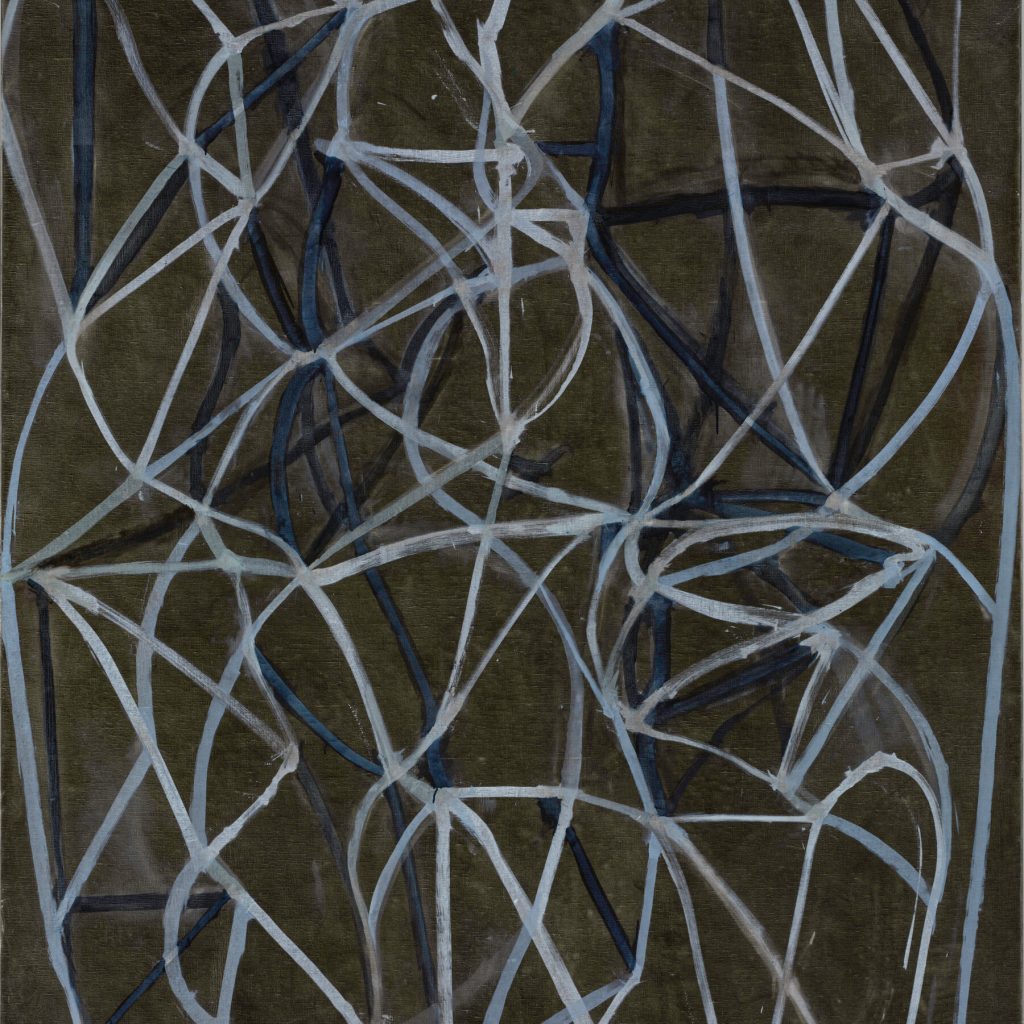

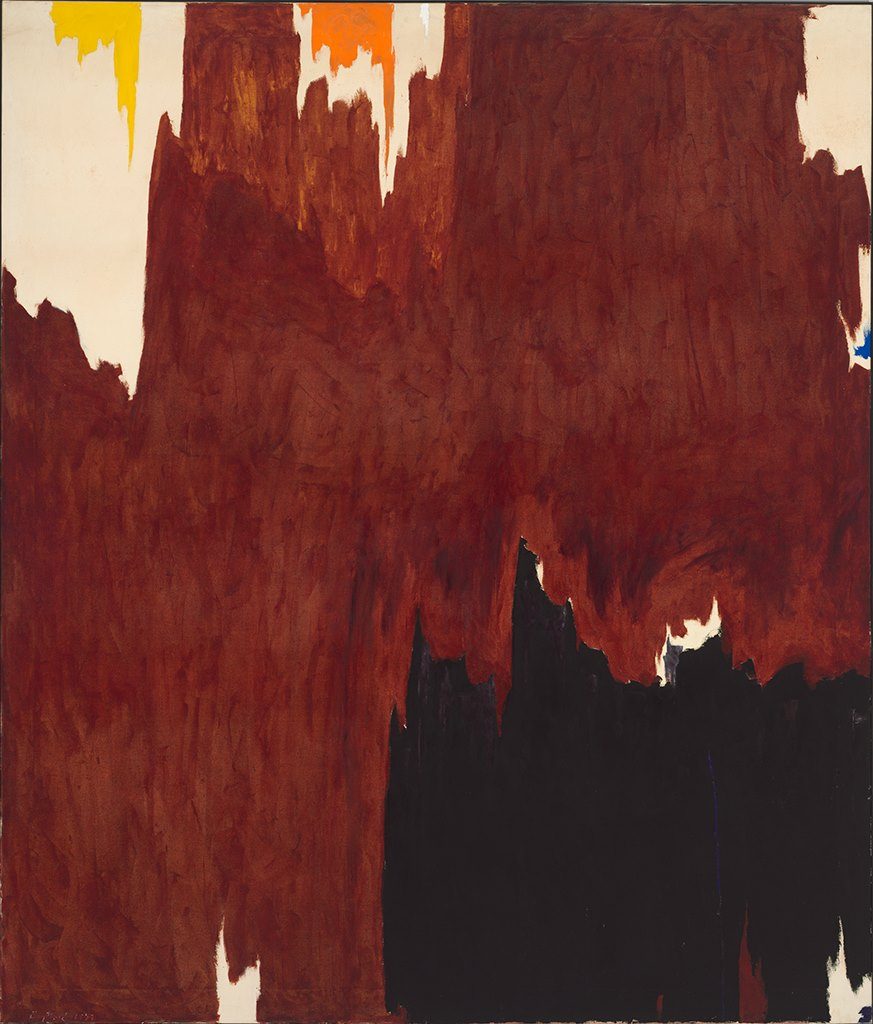

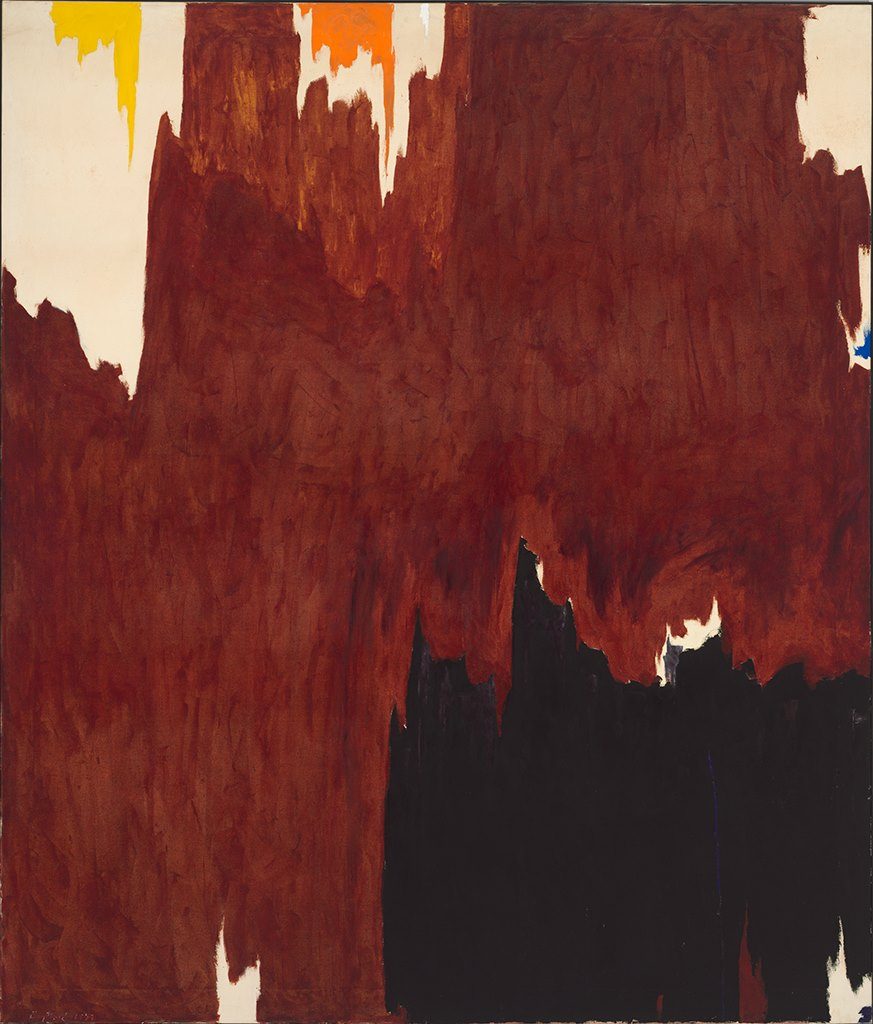

That has opened the floodgates at museums across the nation, with more than $100 million worth of art from institutional collections heading to auction houses this fall. About $65 million of that is expected to come from Baltimore’s sale of 3 (1987–88) by Brice Marden, 1957-G (1957) by Clyfford Still, and The Last Supper (1986) by Andy Warhol.

Andy Warhol, The Last Supper (1986). © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image courtesy the Baltimore Museum of Art.

The letter expresses concern that the Warhol is being sold privately—apparently for $43 million, based on the pre-sale low estimates for the other two works—even though another work from the same series fetched $60.8 million at Christie’s New York in 2017. The letter, drafted by lawyer Laurence J. Eisenstein, claims the piece is being sold at “a bargain-basement price” and that “the BMA did not sufficiently exercise its fiduciary duty in valuation of the work and seeking competition to maximize the sales proceeds.”

In addition to enhancing endowments for acquisitions and collection care, the Baltimore Museum has said that it plans to use the art-sale proceeds to free up funds to maintain and increase salaries for staff throughout the museum; establish dedicated funds for Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, and Inclusion (DEAI) programs; eliminate admission fees for special exhibitions; and begin offering evening hours.

But the donors’ letter argues that the curatorial staff who voted unanimously to approve the sale of the work were incentivized to do so by the fact that they would benefit directly from the plan, which they contend is a violation of AAMD guidelines.

Furthermore, the letter argues, to part ways with “works of such iconic status… without consideration to their status as Maryland cultural assets” because they guarantee a hefty payday is both a breach of public trust and a violation of AAMD rules.

“We are confident that there are no legal issues relating to the BMA’s deaccession of works by Brice Marden, Clyfford Still, and Andy Warhol,” wrote the museum in a statement provided to Artnet News. The BMA maintains that no one who will see a salary increase from the funds raised through the upcoming sales was involved in the decision-making process.

“Andy Warhol’s The Last Supper was itself purchased through funds made possible by the deaccessioning of a painting by the Abstract Expressionist master Mark Rothko,” the museum noted. “Collections management—which includes both accessioning and deaccessioning—is a critical aspect of curatorial practice and is not one that is purely additive.”

The statement also defends the decision to offer the Warhol privately as “the most effective format for the sale.” Sotheby’s did not respond to inquiries from Artnet News.

Clyfford Still, 1957-G (1957). City & County of Denver, Courtesy Clyfford Still Museum/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“Sotheby’s stands in full support of the Baltimore Museum of Art’s thorough deaccession process and their pioneering plans for the future of the institution,” said the auction house in an email to Artnet News. “Sotheby’s sales of works on behalf of the museum will proceed as scheduled.”

The donor letter, meanwhile, also details the importance of all three works—contrasting them with the seven works by white male artists the BMA sold in 2018 to raise money for acquisitions of work by women and artists of color, which were minor examples or duplicative of other pieces in the collection.

The Marden canvas is the only painting by the artist owned by the BMA, and it is highly unusual for institutions to sell the work of living artists.

At the time of its acquisition, the Warhol represented an important diversification of the collection to include a prominent LGBTQ artist, and is the most significant work by the Pop art great at the institution, the letter contends.

The Still painting, a rare gift by the artist in his lifetime, is the only work of his at the museum, or in a public collection in the entire state, even though Still lived in Maryland for nearly 20 years.