A new Bauhaus Museum in Germany stands on the ideological fault lines of the country’s tumultuous 20th century. One hundred years after Walter Gropius founded the world’s most famous art and design school in Weimar, the city has staked its claim as the birthplace of the influential movement by unveiling the new museum over the weekend. Housed in a custom building, its architecture is a powerful political symbol in its own right.

Both the inaugural displays and the building itself are a testament to the creative foment at the time—and the Nazi regime that quashed it. At a time when the far right is rising in Germany, the institution strikes a resonant tone.

The museum’s inauguration is one of the many events taking place around Germany this year as the country celebrates the Bauhaus centenary. The Bauhaus school’s two other homes, in Dessau and Berlin, are also getting new museums, with Dessau’s due to open in September and Berlin’s in 2020. And although the Dessau period is the most well known, largely because that is when the architectural department was added to the school’s program, the Bauhaus principles, as well as its core aesthetic tenets, were born in Weimar.

The Bauhaus Museum Weimar presents itself with white light bands on the façade on the day of its opening. Photo: Martin Schutt/dpa-Zentralbild/dpa.

It was a surprise when in 2012 the Klassik Stiftung Weimar, the leading regional art foundation, announced that a relatively novice German architect—who had, in fact, not built anything at all at that point—had won the international design competition for the museum. Heike Hanada, who teaches at the Bauhaus University in Weimar, beat out more than 500 international architects to the prestigious €22.6 million ($25 million) commission.

Hanada has created a political statement with her minimalist, cube-shaped museum that seems more relevant as a symbol today than anyone could have imagined when it was chosen seven years ago. It addresses the complicated history of the city, which is more than 170 miles southwest of Berlin and after which Germany’s ill-fated democratic republic of 1918–1933 was named. Hanada told the local newspaper the Thüringer Allgemeine that her main goal was to design a museum building “able to stand up to the Nazi architecture in the neighborhood.”

As well as the birthplace of the Bauhaus, Weimar was also where the Nazis built Buchenwald, one of the largest concentration camps erected on German soil. The camp gates were designed by Franz Ehrlich, a prisoner who was a former Bauhaus student.

Visitors at the newly opened Bauhaus Museum. (Photo by Candy Welz/picture alliance via Getty Images)

Ideological Battleground

The Bauhaus Museum creates a link between architectural remnants of the conflicting ideologies that thrived in Weimar in the 20th century: some progressive, some oppressive.

A staircase leading to the top-floor galleries, for example, frames a view of the memorial site of Buchenwald. On one side of the museum, there is a sprawling public park created in the 1920s, which marked a new, modernist approach to urban life and the need for places of recreation. On the other side, there is the massive Gauforum, a Nazi colossus built to house administrative offices in the 1930s. Both are visible from inside the museum’s main foyer and upper floors. Behind the Nazi-era building, museumgoers can also see a German Democratic Republic-era high-rise.

“It becomes plain here what happens when you heedlessly run after certain ideologies,” Wolfgang Holler, the director of Klassik Stiftung Weimar, told AFP. “These fascinating juxtapositions say so much about how this country sees itself.” And ideological battles, of course, are not just for the history books: Next month, the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) is poised to make strong gains in the State of Thuringia in the upcoming elections for the European Parliament.

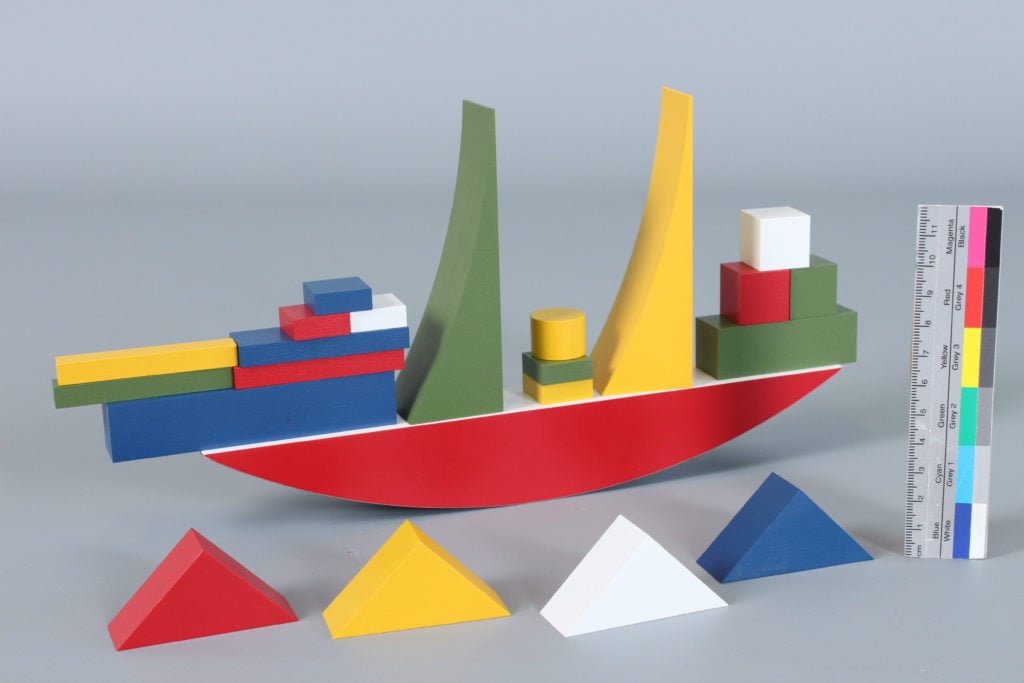

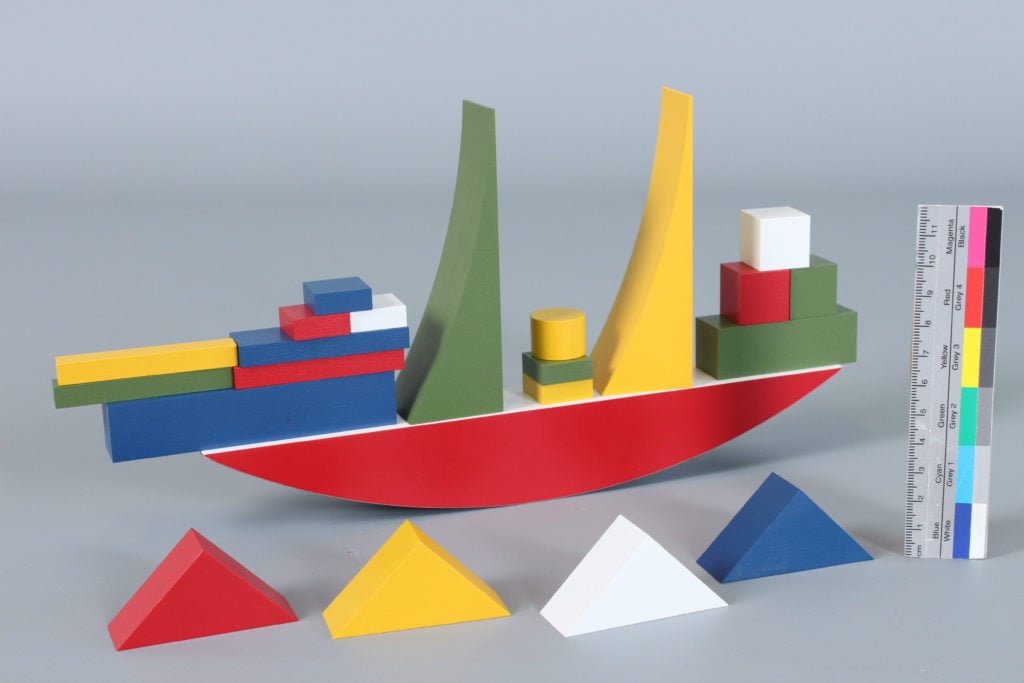

Alma Siedhoff-Buscher, Small Ship-Building Game (1923). Hersteller der Nachbildung/ Designer of the reconstruction: Naef Spiele AG.

One of the highlights of the new museum’s display is a collection of 160 objects made in the original school’s workshops that Gropius donated to the city in 1925, when it relocated to Dessau. The move followed politically motivated cuts to its budget. The collection includes everyday objects rendered in clay, metal, and porcelain as well as woven tapestries. The earliest Bauhaus collection, it was assembled by Gropius himself, who from from the start recognized the need to create an archive for the experiments that took place in the hothouse atmosphere of art and design.

It is ironic, and fortunate, that Weimar’s city fathers did not appreciate the importance of Gropius’s donation at first and let it languish in storage for years. Benign neglect meant that it was not destroyed or dispersed in the Nazi era.

Visitors view furniture in the newly opened Bauhaus Museum. (Photo by Candy Welz/picture alliance via Getty Images)

Before the Bauhaus

Weimar’s nearby Neues Museum also re-opened recently with an exhibition about the advent of Modernism in the city in the first two decades of the 20th century. It focuses on the main figures who ensured that a community of designers and artists could pursue new aesthetic ideas, such as realism, Impressionism, and Art Nouveau in Weimar, away from the capital and the disapproving eyes of the Kaiser. (In fact, the first exhibition of Impressionist art in Germany took place in Weimar.)

This context helps explain why the Bauhaus emerged in Weimar as opposed to Berlin. The exhibition acknowledges the importance of the charismatic Belgian designer Henry van de Velde, who founded the school of applied arts and crafts and the school of arts in Weimar, which Gropius then took over and united to form the Bauhaus.

The kitchen of the Haus am Horn (1923) on display in the new Bauhaus-Museum Weimar. Photo by Sean Gallup/Getty Images.

Tucked away outside the city center, on the edges of a park where Goethe’s garden house forms one of the main tourist attractions, there is an overlooked early Bauhaus gem of a building. Created for the first Bauhaus exhibition in 1923, the Haus am Horn is Weimar’s only example of authentic Bauhaus architecture. Opening to the public in May, its interior is the earliest example of the solutions the school proposed for living in modern times. The original kitchen and some of the functionalist furniture from the building are on display in the new Bauhaus Museum.

There are nods to the way the Bauhaus went on to shape the future as well. A work by the Berlin-based Argentinian artist Tomás Saraceno hangs high above the new museum’s lobby. Saraceno’s site-specific work is formed by interwoven clusters of mirrored spheres linked together and suspended from the walls and ceiling by a net of web-like fibers. It is a visual metaphor for the way Bauhaus’s ideas spread around the world. (Its students came from as far afield as Japan.)

Visitors in the newly opened Bauhaus Museum. (Photo by Candy Welz/picture alliance via Getty Images)

Many of the Bauhaus’s founding members and students fled Germany in the Nazi era⸺Gropius and the school’s third and final director Mies van der Rohe headed to the US, along with Josef and Anni Albers and László Moholy-Nagy, among others. Saraceno’s sculpture also suggests the networks created between communities, ideas, and different artistic disciplines that the Nazis failed to stamp out when they forced the school to close.