Art World

From Dirty-Joke Theory to True Crime Classics, Here Are 17 Books That Have Inspired Some of Today’s Leading Artists

From a philosophy of dirty jokes to a true-crime classic, artists share the surprising titles that have influenced them.

From a philosophy of dirty jokes to a true-crime classic, artists share the surprising titles that have influenced them.

Artnet News

It’s officially the dog days of summer, and a perfect time to catch up on our reading lists. To get inspired for the fall, we asked a group of leading international artists about the books, old and new, that have influenced them most. From a book about dirty jokes to artist biographies to true crime—here are 16 books that have made a lasting impression on some of today’s top artists.

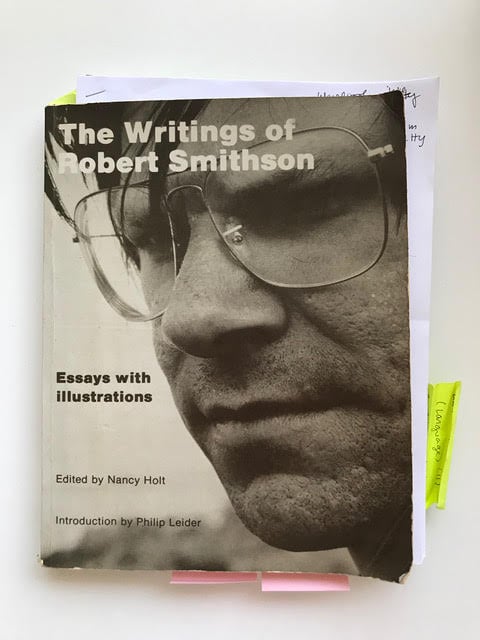

The Writings of Robert Smithson, courtesy of Diana Thater.

“The Writings of Robert Smithson, specifically the edition designed by Sol LeWitt, is a book I discovered in the late 1980s, at about the same time that I first saw Smithson’s film The Spiral Jetty. Smithson’s artworks, his writing, and his films are of a piece. They all belong on the continuum of his distinct artistic practice and together they form a complex but full picture of his work. LeWitt’s design is perfection. It looks and feels like a college science workbook and, sometimes, that’s exactly what it is.”

Gershon Legman’s The Rationale of the Dirty Joke, published by Grove Press in 1968. Photo courtesy of Walter Robinson.

“My book would be Gershon Legman’s The Rationale of the Dirty Joke, published by Grove Press in 1968, as it happens the same year as the vulgar literary bestseller Portnoy’s Complaint. Legman, a self-taught scholar and joke collector who moved from New York to the South of France, where he died at age 91 in 1999, specialized in the Freudian analysis of jokes as sexual folklore. Dirty jokes unveil the joke-tellers own neuroses, compulsions, and guilt, Legman wrote, and constitute a disguised verbal aggression directed at the listener, with the hostility supposedly deflected by laughter. Hostility disguised as wit, that is the secret of jokes. And, perhaps, of the avant-garde.”

Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. ©Penguin Random House.

“Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man continues to inform my work in ways I am not totally conscious of. It reads as if it could have been written yesterday, in a tragic sense. There are so many ways I can try to relate its continued relevance, but for personal reasons I will extract the following two quotes:

‘For, like almost everyone else in our country, I started out with my share of optimism. I believed in hard work and progress and action, but now, after first being ‘for’ society and then ‘against’ it, I assign myself no rank or any limit, and such an attitude is very much against the trend of the times. But my world has become one of infinite possibilities. What a phrase – still it’s a good phrase and a good view of life, and a man shouldn’t accept any other; that much I’ve learned underground. Until some gang succeeds in putting the world in a strait jacket, its definition is possibility.’‘And the mind that has conceived a plan of living must never lose sight of the chaos against which that pattern was conceived. That goes for societies as well as for individuals.’

“The Skin-Ego is a book by French psychoanalyst Didier Anzieu (1923-1999) on the relations between the skin and the formation of the ego. For Anzieu, the ego is the projection in the psyche on the surface of the body. The Skin-Ego is at once a sac containing the pieces of the self, an excitation screen, a surface in which signs are inscribed, and a guardian of the intensity of instincts. Anzieu’s Skin-Ego draws parallels between the biological functions of the skin, and the psychological functions of the ego.”

Sinatra’s Frank Sinatra: A Man and His Art (1991).

“I hate celebrity artists, but Frank Sinatra’s paintings are like Sparknotes of Modernism. He made hundreds of cheap interpretations in Palm Springs of Ad Reinhardt, Julian Schnabel, Francisco Clemente, and others. I admire how he literally tried everything: Futurism, Abstract Expressionism, Color Field, Minimalism. They’re earnest and shitty copies at the same time.

The Mike Kelley book is one of the only artist books I actually enjoyed reading cover to cover. There’s a ton of short interviews with a whole range of people, from Richard Prince to John Waters, and some of the interviews are really short and awkward and you can tell it was forced for a magazine or publisher.”

Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions by the English schoolmaster Edwin Abbott, first published in 1884 by Seeley & Co. of London. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Louise Bourgeois, Elisabeth Bronfen, Donald Kuspit (Author), Philip Larratt-Smith (Editor), The Return of the Repressed: Psychoanalytic Writings by Louise Bourgeois.

“This says it all.”

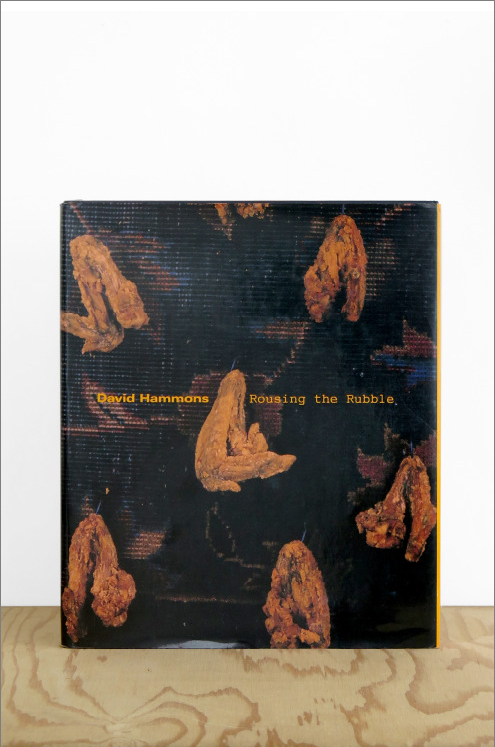

David Hammons’s Rousing the Rubble (1991).

“It was probably 1994 or 1995 and I was a high school student taking Saturday art classes at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. One of the teachers showed me Rousing the Rubble and I remember being made uneasy by the images of Hammons printing with his body. I love Hammons’s work now, but I wasn’t ready for it then, and it always reminds me that time, situation, and context are a part of thinking about an artwork and a practice.”

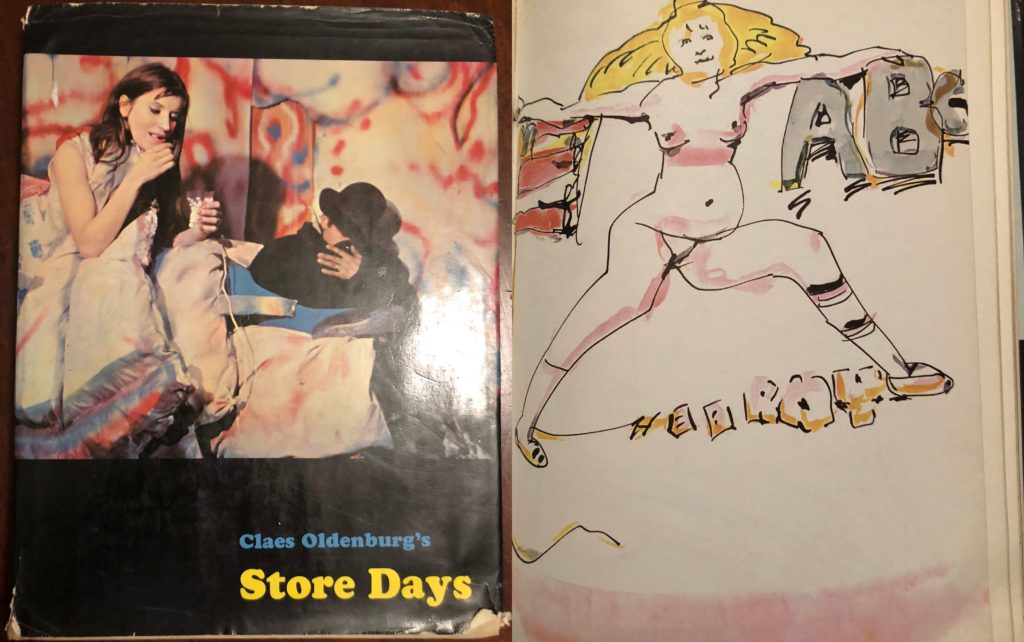

Claes Oldenburg’s Store Days personal copy of Deb Kass.

“I can tell you about my first, and still incredibly influential, art book: Claes Oldenburg’s Store Days. I bought it from the Philadelphia Museum book shop when I was in high school. Oldenburg and this book taught me that ‘great art’ could have a sense of humor.”

Aruna D’Souza’s Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in 3 Acts (2018). Courtesy of Badlands Unlimited.

Jules Romains’s Donogoo-Tonka or the Miracles of Science: A Cinematographic Tale.

“I love this book by the French author and philosopher Jules Romains for many reasons. The title itself is such a perfect hook—it promises the unseen, has a bewildering fantasty/kitsch/utopian feeling about it, and gives just a hint of the form. The form is in fact the reason I mention this not as a literary work, but as an art book. Written in an era when cinema was a fairly new medium, exciting the imagination of avant-garde writers for its revolutionary potential, this book takes the shape of a film script with inter-titles that reference silent film (usually a functional box that would mark changes of time, place, or plot summary).

Romains goes beyond the conventional use, placing the inter-titles in a subversive relation to the script itself, using them to introduce images such as posters, newspaper clippings, and telegrams; thus making a hybrid visual novel, literary work, and (mock) silent film scenario.

The plot involves a suicidal man on a mission to restore credibility to a geographer, whose academic prospects are almost ruined after he spreads the word about a fictional city in South America by making the place real. It has some obvious flaws—most glaringly it lacks criticality on colonial perspectives and racism, particularly striking given that Romains started the Unanimism movement, which emphasized communal spirit.

However, I’m at a point in time where I watch my little daughter explore all sorts of utopian lands, and so I take the story for what it is: a great tale, an amazing example of geography as fictional matter and spatial urban imagination.”

Calvin Tomkins’s Marcel Duchamp: A Biography (1996).

“When I was about 19 I read half of Calvin Tomkins’s Marcel Duchamp: A Biography and it showed me that one can take play seriously and be taken seriously. The part where he retires from art to become a full-time ‘respirator’ stuck with me—that ideas and action are the ultimate work of our lifetime.”

Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (1966).

“As a young boy in the 1970s I first saw Truman Capote on the Dick Cavett Show and was mesmerized. The next day I started to read every book I could find of his. What resonated with me was how he embodied the journalist, novelist, biographer, and autobiographer, blurring the lines between these writing conventions. Informed by Capote I begin each project with intensive research, which results in a cross-wiring of fact and fiction.”

K.D.’s Headless (2015). Courtesy of Triple Canopy.

“I must confess that, for me, it’s been a long process waiting for this book. It all started in 2009, when a former colleague at the library in Bucharest returned with a truly intriguing gift: the first five chapters of Headless, an artist’s novel initiated by artist duo Goldin + Senneby as an investigation of the offshore financial industry.

A year later, the artist Ioana Nemes told me about a puzzling performance the duo had in Kadist via one of their acolytes as part of the writing, making, and performing of the future book. Fast forward to 2013, I decided to include the little five-chapter-booklet in an exhibition I curated at Oberwelt in Stuttgart called ‘œconomy, an already tumultuous landscape where phantasms cross’—paying special attention to the transgressive knowledge of a particular type of ‘ersatz economies’ coming from the art scene.

Two years later, Headless is complete, and doesn’t disappoint. On the contrary, the play with fictionalization, appropriation, the digging for hidden facts about corrupted corporations, turns this mystery novel into something we might never fully decipher—like the economy itself. The polyphony of voices of various contributors from art, economics, literature, and academia, as well as the writing process that includes performances and lectures, manufactured from a distance by Goldin + Senneby, makes it extremely puzzling at times. It is loose in structure, and chaotic, too. Yet it’s precisely this impossibility to entirely incorporate such a complex process that makes Headless such a memorable piece of artistic research, knowledge, and speculation about economy.”

David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest (1996). Courtesy of Little, Brown.

“It’s the easiest question to answer, but breaking down why I like it into a few lines is harder. Wallace deals with entertainment, sadness, and addiction in ways that I didn’t think were possible. The experience of reading it—about 1,100 pages altogether—was a deep dive. Written in the 1990s, the fictional story takes place in a future that looks a lot like our own: the many sub-plots circle around the story of a video that is so entertaining to watch that no one is able to view it and live to tell those who haven’t seen it what is about. They all die of dehydration, because they can’t tear themselves away from the images.”

Olivia Plender’s A Stellar Key to the Summerland (2007). Courtesy of Bookworks.

“My choice is A Stellar Key to the Summerland, a comic book by British artist Oliva Plender, is a savant-peep into the Spiritualist movement (a religious and social reform movement) through gorgous hand drawings, and immersive narrative. Plender is channeling her long-term research into movements organized by groups, in order to empower individuals to bring to surface hidden truths and bits of history.

A Stellar Key to the Summerland is a truly captivating read. It’s quirky and political, light and meaningful, somber and cryptic, loud, and frenetic—sometimes all at once. On top of it all, the most glorious aspect for me was to understand where the urgency lies: her fascination with the past conjures in many unexpected ways a critique of the present and allusions to the future.”