Bridgerton, Netflix’s wildly popular new period drama, is a whimsical feast for the eyes replete with easter-egg colored dresses, sumptuous and sprawling estates, and yes, a fair share of art.

(Be warned: spoilers ahead!)

Set in Regency-era England, the steamy series, created by Chris Van Dusen and produced by Shonda Rhimes, follows the travails of two competing families—the old money Bridgertons and the nouveau-riche Featheringtons—as their daughters navigate the 1813 debutante season.

The plot centers on the complex romantic tango between Daphne Bridgerton (Phoebe Dynevor) and perennial bachelor Simon, Duke of Hastings (Regé-Jean Page), who are friends turned accomplices, turned lovers, turned enemies, and back to lovers again. Whew!

A close look reveals the series set is also brimming with both insightful (and sometimes playfully inaccurate) art-historical details. To start, the Bridgerton family’s pale blue decor is supposed to be a reference Wedgwood ceramics. Museums also make major appearances: Bath’s Holburne Museum, the Wilton House Museum near Salisbury, and Greenwich’s Ranger’s House (home to the Wernher Collection) were all filming locations, and some of their art collections make cameos as well.

With a confirmed second season on the way, we’ve rewatched all the episodes and pinpointed some of our favorite art-centric moments in the show.

18th-Century Portraits of Queen Charlotte

& a Reimagined Portrait by Diego Velázquez

Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. Collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Though it may seem strange to start this story with paintings that don’t actually appear in the show, 18th-century portraits of Queen Charlotte are essential to understanding the fantasy-laced premise of the show.

Bridgerton’s Queen Charlotte (Golda Rosheuvel) is based on the real-life German-born Queen of England, Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1744–1818), who is often known as England’s first Black queen.

Screenshot from Bridgerton. Image courtesy of Netflix.

Rumors of Queen Charlotte’s mixed-race heritage date to her lifetime, but have resurfaced over the centuries largely because of portraits of the Queen that, to many eyes, hint at a biracial appearance. The scholar Mario de Valdes y Cocom has famously argued that the Queen’s African heritage can be traced back to Margarita de Castro e Souza, a 15th-century Portuguese noblewoman, herself believed to be descended from a Black branch of the Portuguese royal family (the 11th century’s King Afonso III of Portugal and one of his mistresses, Madragana).

Though Valdes y Cocom’s research has been widely contested (and is itself partially based on outdated theories of physiognomy), the story of Queen Charlotte has endured and even flourished.

In Bridgerton, the fantastical reimagining of Queen Charlotte underpins the show’s depiction of a multi-racial nobility; here, England’s first Black queen has integrated into society fully, and on every social stratum.

Diego Velázquez, Juan de Pareja (1650). Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

All this has art-historical implications. In an incisive blog post about the paintings of Bridgerton by Richard Rand, associate director for collections for the J. Paul Getty Museum, Rand notes that the set includes a reconfigured portrait based on Diego Velázquez’s Portrait of Juan de Pareja.

Pareja was a mixed-race, enslaved assistant in the artist’s studio. In Bridgerton, however, Pareja’s “head and collar have been digitally superimposed on a three-quarter-length figure facing left,” Rand writes. “The resulting composite image transforms an actual portrait of an enslaved artist into an imaginary one of a Black aristocrat, presumably meant to represent one of the Queen’s ancestors.”

These are not the only reimagined portraits in the show. Alongside famous paintings by Anthony Van Dyck, Thomas Gainsborough, and Joseph Wright of Derby, Bridgerton features a pair of portraits of Queen Charlotte and King George made to resemble the actors that play them, Golda Rosheuvel and James Fleet.

The Landscape That Sparks the Love Story

Screen capture from Bridgerton. Image courtesy of Netflix.

The series’ star-crossed lovers, Daphne and Simon, the Duke of Hastings, begin as acquaintances feigning romantic interest for mutual benefit: Daphne will be seen as a sought-after debutante, inspiring more suitors; and Simon, the resolute bachelor, will be momentarily freed from the pressure to wed.

But as their antics develop, so do genuine feelings—and luckily for us, simmering emotions come to a head in (what better place?) a painting gallery.

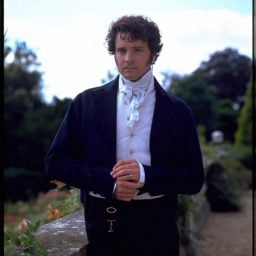

In episode three, the debutantes and suitors have gathered at Somerset House to see the Royal Academy’s summer exhibition. The brooding Duke of Hastings, it turns out, is also a patron of the arts and has donated a trove of family paintings to the exhibition.

In the scene, Daphne and Simon share a moment of intimacy while gazing at a landscape that once belonged to Simon’s late mother. “The other paintings are certainly very grand and impressive, but this one… this one is intimate,” Daphne remarks. Standing side by side, their hands briefly touch—a forbidden caress for those yet to be wed.

Aelbert Cuyp, Landscape with the Flight into Egypt (circa 1650). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

What painting elicited such a scandalizing gesture? To our eyes, it seems to be Aelbert Cuyp’s Landscape with the Flight into Egypt, which belongs to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Sir Henry Granville’s Anachronistic Paintings

Screen capture from Bridgerton. Image courtesy of Netflix.

The Bridgerton siblings all seem to have an artistic flair. Eloise wants to become a writer, Daphne composes music, and Benedict, the ennui-filled second son, dabbles in painting. (In one episode, the angsty brother paints a formal portrait of the newly wedded Duke and Duchess of Hastings set against a curtained backdrop).

Benedict, yearning for a more expressive outlet, befriends Sir Henry Granville, a famous artist in London society. Granville, who is publicly known for his reserved portraits, invites Benedict to a party at his home, where—it turns out—a nocturnal life drawing studio is a den of forbidden pleasures.

Male and female artists and models abound, smoking cigarettes and generally being mischievous, while throughout the home, guests engage in myriad publicly taboo sexual entanglements (Granville is gay, and is closeted only to the larger aristocratic world). Rand describes the scene as “a louche sanctuary liberated from the constraints of aristocratic culture.”

Orazio Gentileschi, Danaë (c. 1623). Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Hanging on his walls are recreations of some very real paintings: Orazio Gentileschi’s Danaë (circa 1623); Hendrick Goltzius’s The Sleeping Danaë Being Prepared to Receive Jupiter (1603); and French Neoclassical artist Jacques-Louis David’s not-quite-contemporaneous Cupid and Psyche (1817), along with his male nude Patroclus (1780).

Though it’s comical to imagine these paintings as the product of a 19th-century English aristocrat’s hand, together, they hint at another phenomenon altogether.

A copy of Jacques Louis David’s Patroclus hangs in the background of Lord Granville’s studio.

Across the centuries, artists have turned to mythological subject matters as a means of skirting contemporaneous taboos, in this case, sexuality. “As characters from classical mythology, Danaë and Psyche were imagined as precious objects of desire, to be hidden away, manipulated, and, in the case of Danaë, violated by the gods. Here, they are painted stand-ins for the trapped young ladies in Regency high society, forced into desperate maneuvers to attract husbands,” Rand notes in this blog post. In Daphne’s case, these mythological stories hint at the deceit and trickery centering around her own sexual naivety.

Eloise’s (Proto) Feminist Art History

Screen capture from Bridgerton. Image courtesy of Netflix.

Eloise Bridgerton, the plucky second daughter, fancies herself a writer and something of a detective (she’s determined to discover just whom the gossip columnist Lady Whistledown really is). What’s more, she bristles against the era’s neatly defined roles for women, and longs for a life and career beyond simple marriage.

The show’s proto-feminist, Eloise imbues contemporary perspectives into the 1800s—and, luckily for us, she has opinions about art as well. While attending the Royal Academy’s summer exhibition, she and her friend Penelope Featherington gaze up at the artist’s Louis-Jean-François Lagrenée’s painting Venus and Her Nymphs. Put off by both the painting and the general spectacle of the debutante season, Eloise concludes, “Like all of these paintings, it was done by a man, who sees women as nothing but decorative objects.”

As for her preferred artistic tastes, one need only look in Eloise’s own bedroom. There hangs a portrait of Mary Wollstonecraft, writer, women’s rights activist, and mother of Mary Shelley.

Of the choice, production designer Will Hughes-Jones told Town & Country: “We felt that Mary Wollstonecraft would have been her hero… [Eloise is] the outspoken detective; she’s well-read; she’s opinionated and feisty.”

A Nod to a Pioneering 17th-Century Woman Artist—and a Snub to Another

Rosalba Carriera, A Young Lady with a Parrot (circa 1730). Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

While Eloise imagines life outside of societal convention, she still exists within the bubble of aristocratic society. The show’s most unconventional female character is arguably Siena Rosso, an opera singer engaged in a clandestine relationship with Anthony Bridgerton. Knowing a scandal will ensue, Anthony, the eldest son, can’t bring himself to make their relationship public.

Screen capture from Bridgerton. Image courtesy of Netflix.

A world-weary Rosso ultimately breaks off the affair, choosing her art and personal freedom over the conventions of aristocratic society. In the final episode of the first season, a well-placed artwork in Sienna’s bedchamber hints at her pioneering role in the story: A Young Lady with a Parrot by Rosalba Carriera.

Marie Guillelmine Benoist, Madame Philippe Panon Desbassayns de Richemont and Her Son, Eugène (1802). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A 17th-century Venetian Rococo painter, Carriera was one of the only—and among the most famous—women artists of the period. And in this fictional setting, she acts as a predecessor to Sienna.

Benedict Bridgerton calls this Marie Guillelmine Benoist painting “too cold.”

But it’s not all good news for women artists in the world of Bridgerton: in an earlier episode, the 19th-century painter Marie Guillelmine Benoist is snubbed when her 1802 portrait Madame Philippe Panon Desbassayns de Richemont is attributed to none other than Sir Henry Granville. What’s more, Benedict Bridgerton dismisses the work, saying “Where’s any sense of the subject’s spirit? And the light. Given the quality, I do wonder why the piece was not skyed with the other daubs.” The injustice!