Art World

Catherine Opie on Her Majestic New Portraits, the ‘Alt-Right,’ and the Misogyny of the Art Market

For two new shows in Europe, the Los Angeles photographer merges past aesthetics with present politics.

For two new shows in Europe, the Los Angeles photographer merges past aesthetics with present politics.

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

It’s a rainy and sluggish October morning in central London—on the Sunday eve before the frantic Frieze week—but the Los Angeles-based artist Catherine Opie is buoyantly happy. She’s just landed from Norway, where she’s installing her major survey “Keeping an Eye on the World” at the Henie Onstad Kunstsenter in Høvikodden and now she is (briefly) in London for the opening of her first solo outing at Thomas Dane Gallery.

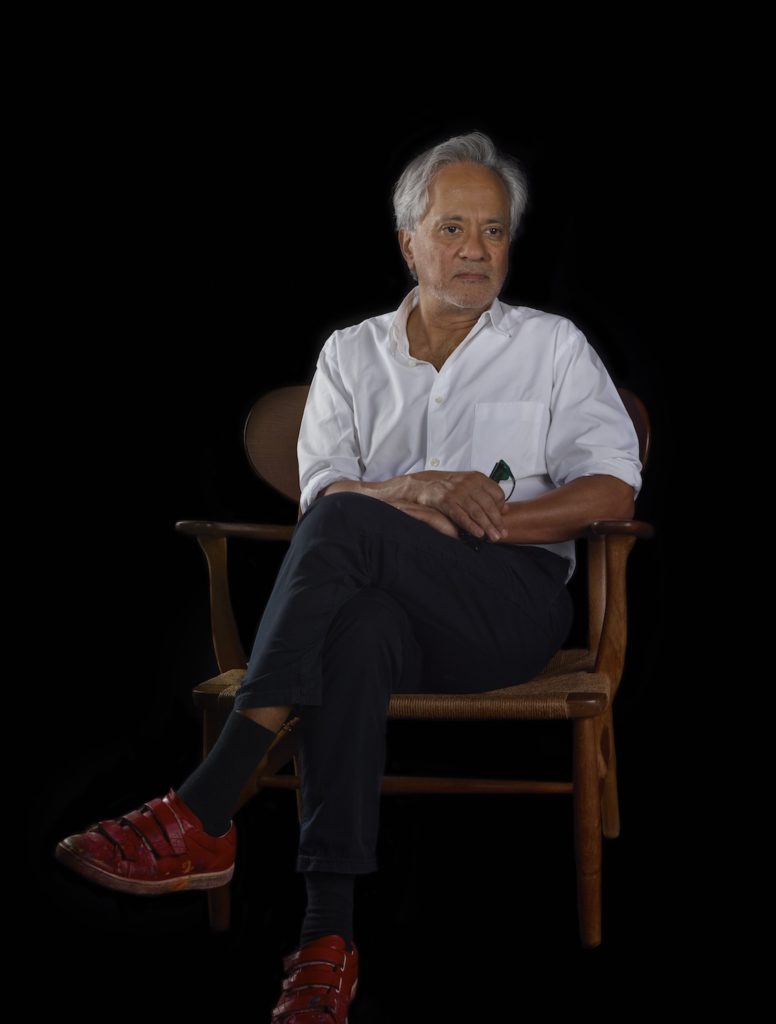

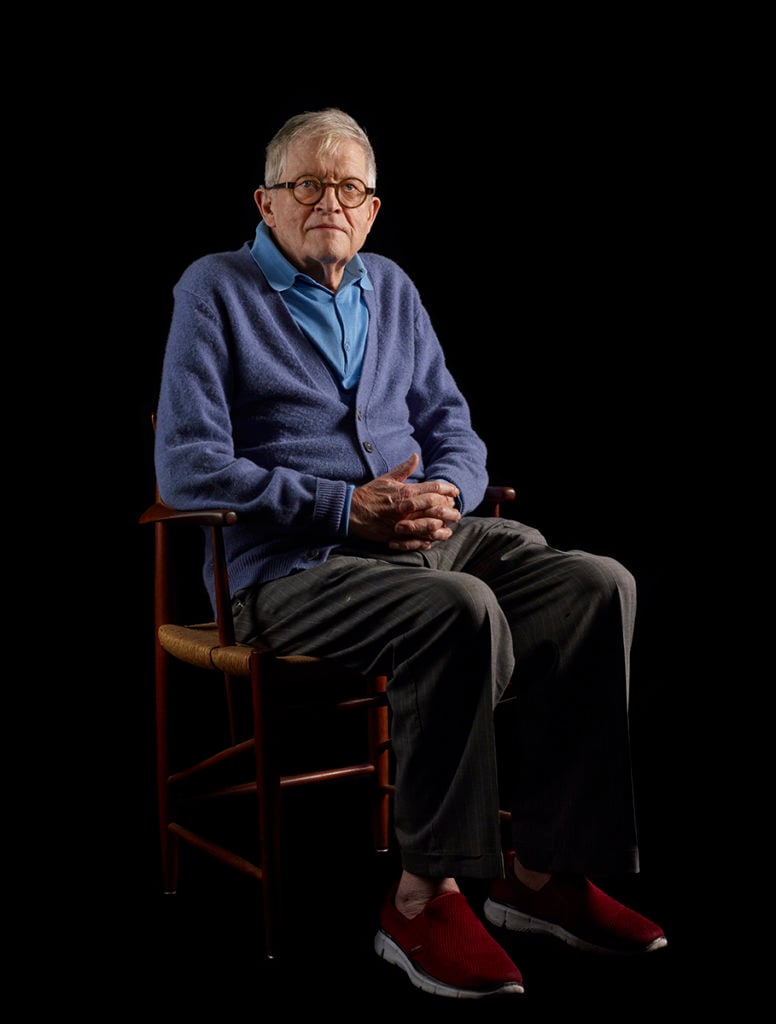

With the no-nonsense title of “Portraits and Landscapes,” the show features one large-scale abstracted portrait of the British coast and 13 Old Master-influenced portraits of renowned contemporary artists and figures, including David Hockney, Anish Kapoor, Duro Olowu and Thelma Golden, Gillian Wearing, Isaac Julien, and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye.

Open, generous with her time, and bursting into laughter on several occasions, Opie is the perfect interviewee. She is fearless on tough subjects like the Trump presidency, the rise of hate crimes in the US, and the rampant misogyny in the art world, which isn’t too surprising considering that Opie established her career with work that documented the queer and leather communities in America.

We spoke at Thomas Dane Gallery as Opie finished installing the show.

How did you choose the sitters for this show at Thomas Dane?

I tend to photograph people that I’ve know for a long time, but this series of portraits that I’ve been working on for the last five years features mostly people working in the creative industries—poets, writers, fashion designers, artists.

Sitters in this specific body of work are mostly artists that I really admire from different generations, which is really important to me. But something interesting about these works is that the majority of the artists also work with portraits themselves, except for Anish Kapoor. But one thing I like about Anish’s portrait is that, as I was photographing him, I was thinking about how David Hockney would paint him, so I did something that I never do in my work, but that David would, which is to cut off the tip of a shoe. In the case of the painter Celia Paul, in her own self-portraits we never see her hair and she folds her hands on her lap, so I tried to reconfigure that and look at her in a new way.

Catherine Opie, Anish (2017). ©Catherine Opie, Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

So they are like meta-portraits, where you riffed on the artists’ practices.

Yeah, a little bit. They are meant to be very formal, to hold somebody. It’s important to me that these portraits go beyond the idea of the snapshot, as if the black backdrop were the subconscious. They are very controlled portraits, highly staged, to the point where I even place their hands where I want them to be, and I tell them where to look, and position their heads and eyes. I don’t play music when I shoot them, so it’s very quiet and very fast. The portraits look like they must take a really long time because they have this quietness to them, but I try to get people out within 30 to 40 minutes.

These photos share a pictorial sensibility with Old Master works. What’s interesting to you about this classical aesthetic?

At first, in the earlier portraits from the 1990s, it was a strategy to kind of reposition the way we think about the portraits of people from the leather and queer communities. So, if we think about Mapplethorpe, for example, he was very formal, but he was utterly erotic within its formality. In my case, I was using fields of color—and I think Holbein was my inspiration on that—getting people from my community to be really noble within it.

In a photographic documentary practice, normally we would see leather folk in their house, with their accoutrements around them. For me, it was a question of creating space in the image so that the body becomes a form of architecture in relation to the structure, while at the same time being about the person in the community.

I like to create a different way of entering a portrait, but I’m not an essentialist. I don’t believe I’m making the ultimate portrait of that person, which describes their personality. A portrait is a shared experience, it’s moment in time, and that’s what photography does. So even though I employ some ideas out of the history of painting, my work has to always remain within the photographic realm.

Catherine Opie, Celia (2017). ©Catherine Opie, Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

What’s the relevance today of the Old Master aesthetic?

Actually, I get really annoyed with artists that copy Old Master paintings verbatim. I don’t think it does anything; no one is wearing lace today. Instead, if you can make a portrait that makes you think about painting but featuring contemporary elements, and that contains the sensibility of the person, then I feel like you are merging those ideas together in a much more interesting way.

But I think one of the reasons we go back to Old Master paintings is not necessarily about wanting to look at Henry VIII, but because they represent a certain history and we have a connection to this shared sense of history. So for me, to create a new history while looking at history is a much broader conversation that deals with ideas of longing and nostalgia. And with my earlier portraits, I’d say that in some ways they were really radical when I made them in the 1990s but now they don’t seem that radical anymore, because things have changed on some many levels. As an artist, I’m interested in having a conversation with the history of representation, exploring what becomes iconic and how to break that.

I don’t think my portraits are really that different from other works coming from the same lexicon of art history, but they give you the people right now, in the moment, and because most of them are also known artists, they explore our relationship with memory, the sublime, longing, and how to create allegory right now, in a moment in history in which everything is photographed all the time—not only from surveillance cameras, but also from people’s phones.

Speaking of phones, portraiture has gained immense currency today—meaning selfies, Instagram, and fictional self-representation à la Cindy Sherman. Is the distinction between high culture and low culture, fine art portraiture and mass portraiture important to you?

I consider myself a formal photographer and I can’t break from that, even if I take a lot of snapshots with my camera phone. But I actually did a class at UCLA to unpack this phenomenon, which I called “Selfie/self-portraiture #whatthefuck.” We explored the appeal of immediate satisfaction.

I think the selfie has its place culturally, but I don’t know if it has its place historically—or artistically, which might sound super snobby, and I’m so not a snob at all, but I really question that, and I make my students question that too.

Catherine Opie, Thelma & Duro (2017). ©Catherine Opie, Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

With what camera did you shoot these large-scale portraits at Thomas Dane?

It’s a Hasselblad 82 with an 80-megapixel back. When I switched to digital it was because it could do the same that that my 8×10 or my 4×5 cameras could do. I need to be able to read every pimple, every scar. Detail is very important to me.

I switched to digital with the series “High School Football” around 2008 because I couldn’t take the 8×10 camera in the football field and get the quality that I wanted. I had won a $50,000 prize and I bought a $50,000 camera. My partner was like, “Are you kidding me?”

Was it difficult to transition from analogue to digital?

I had no problem whatsoever with changing. For me it’s more about the quality of the image, rather than a nostalgic attachment to film and materiality, which I certainly have too. But trying to travel around the world with film post 9/11, trying to develop rolls and have the chemicals be good—I was having a lot of technical problems. And if a single photo costs up to $350 to produce, just from buying, developing, and scanning the film, then it’s better switch to digital—if you can get a good enough camera. I have to say, a lot of artist friends borrow my camera because it’s mostly only commercial photographers who can afford it.

Having said that, I think I’m lucky I learned photography in its analogue period. The work of a lot of younger artists today who work in digital tends to look very much alike. They don’t understand how to push the materiality of the image in relation to film, cause they have no memory of what it is to work in the dark room. I printed every single body of work that I did until Icehouses (2001) by myself in the dark room. Now my assistant does it.

Catherine Opie, David (2017). ©Catherine Opie, Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

You have a vast body of work built on documenting different types of communities and minorities living in America. What do you think about the situation in the US right now with the rise of the alt-right and repressive politics?

Well, I’ve made a new piece in response to it, which will premiere on January 12 at Regen Projects in LA and will then tour to Lehmann Maupin in New York. It’s called The Modernist and it’s a kind of conversation with Chris Marker’s La Jetée, which is one of my absolutely favorite pieces ever. I didn’t know when I started making it that Trump was going to get elected, but then he did and there’s a lot of that in the piece. I was born in 1961 and La Jetée was made in 1962, and the film has everything to do with the fear of WWIII and a nuclear crisis, and yeah, we are on the edge of a nuclear crisis now, but The Modernist mostly deals with the fact the utopic dream is no longer available to us.

So the main character is this artist, who’s played by my good friend Pig Pen, who I’ve photographed for years. The piece is 852 black and white photographs that make up a 21-minute film, featuring this queer, tattooed, trans body. In it, Pig Pen starts burning down the most iconic Modernist houses in Los Angeles, and making this mural in his studio, which is my studio, that I had decked out with Modernist furniture. The piece is a really dystopic tale of destroying what you love so much that you will never be able to obtain it. Modernism was this idea of giving good design to the masses, this middle-class idea, but it turned out to be anything but middle-class. If you want to buy an Eames chair now it’s $5,000, which is not what Charles and Ray Eames had in mind.

So, as the character is making this huge collage on the wall, he starts using the Los Angeles Times articles about the house fires he’s caused—and we did this before fake news was even a thing. But the newspapers in the piece also cover the real news, so there are these little gestures, like Hillary Clinton’s nomination, for example, or a photo of an Eames living room in which a photo of a boy from Aleppo is strapped into the seat has been put in. So The Modernist encompasses everything from the idea of language, the queer body, dystopia, this person’s joy in burning the Modernist houses. It’s a really ambitious piece, which will be screened in a specially designed theater at the gallery.

I thought about it for a number of years and it took two years to complete. It is kind of my way of dealing with what’s happening in my country right now. I’m really happy with it, it’s a really different piece for me to make. As an artist I’m always trying to change my ideas, I don’t have a singular approach to making art. The questions of community, identity, and history are what bind different bodies of work together.

Catherine Opie, Lynette (2017). ©Catherine Opie, Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

So you wanted The Modernist to be political, but not overtly so?

Yes. I teach with Barbara Kruger and I think she’s of our most brilliant artists because sometimes people need to just have words sink into them, and have them sting a little bit. But for myself, I guess I’m trying to complicate language a little bit. Being an out dyke early on and being part of this queer movement was a very delicate dance in relation to how to create visibility within my own community and it required those complicated layers of representation in order to hook the viewer.

How does it feel to be living in America right now?

Oh, it’s horrible. I was really happy to get on the plane and come to Europe. I think there is an anti-Trump feeling here in Europe.

Do you think the queer communities, despite the obvious Trump setback, are more respected and accepted now?

Yeah, they are. I mean, even with things like marriage. Marriage is a hard thing to argue for, right? Who really wants to believe in the institution and ideology of marriage? But it’s equality that’s at stake here. It’s about why, if I were to die, would Julie, my life partner, have to pay all these taxes on all the artwork, while a man and a woman can get married and have all the tax advantages?

So the only reason I was fighting for the institution of marriage was for equality in terms of finances. And I had lots of friends from my generation who were very anti-marriage, thinking it was the wrong cause, but I had to remind them that we all witnessed partners dying of AIDS and not being allowed into emergency rooms, and we saw families come in, who were conservative, and take everything because the other partner didn’t have any rights. So, for me, the question is: if that system exists for heterosexuals, then we have every right to that system as well.

Catherine Opie, Isaac (2017). ©Catherine Opie, Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

Do you think there’s a growing awareness of and respect for gender issues today, particularly as more mainstream figures identify as gender fluid?

Well, yes, but it’s also really bad. The hatred in America right now is bad. A horrible death just happened to a teenager in Missouri. A group of teens killed her, gouged her eyes, and burnt her body. There are so many hate crimes happening in the US now—black people being lynched, transgender people being stabbed. The culture of hate is well and alive in America in the most disgusting way. I would have never imagined that we would be here following an Obama presidency.

You have traveled the whole country to photographing communities as part of your work. Did this spike of hatred and violence surprise you?

No. I have photographed Tea Party rallies, I have mapped out America, and I have mapped out the politics of America, so I know that Conservatism is alive and well. We’ve been fighting the Conservative right for a very long time. Think about Jesse Helms against Mapplethorpe, images being shown on the floor of the Senate. But what’s disappointing is to move so far forward and then move so many steps backwards. It’s not so much about acknowledging that those sentiments are there, but about the fact that when you had such a humanistic, beautiful family representing our country, for it to go to one of the worst people ever—and they are already talking about him being reelected? I just don’t get it. How can that possibly be?

It’s also interesting how many liberals were so anti-Hillary. The misogyny around this was devastating. I talk to men all the time and they are like, “What do you mean misogyny, Cathy? There’s no misogyny.” And I’m like, “Are you kidding me? Look at the art world, tell me there’s no misogyny in the art world!”

Catherine Opie, Gillian (2017). ©Catherine Opie, Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

Where is the misogyny in the art world most visible to you?

I think in the market. Being a professor, I track my students, and I have to say that the majority of my male students seem to do very well after graduating, while for my female students it’s much harder. It’s also visible in the relationship between the quality of the work and money. I’m a very very fortunate artist in that I could make a living out of just being an artist if I chose to, but I also like to teach. I think it’s important to mentor a generation of artists. But I’m one of the very few of my friends that has done this well, and I view my friends as well as my wife as incredible artists that haven’t had the same kind of opportunities I’ve had.

“Catherine Opie: Portraits and Landscapes” is on view at Thomas Dane Gallery, London, from October 3 to November 18. Her survey “Keeping an Eye on the World” is on view at the Henie Onstad Kunstsenter, Høvikodden, from October 6 to January 7.