People

‘Contemporary Art Hates You’: John Waters, the Prince of Puke, on His New Retrospective

The artist discusses the process of putting together his retrospective at the Baltimore Museum.

The artist discusses the process of putting together his retrospective at the Baltimore Museum.

Taylor Dafoe

In 1985, the Baltimore Museum of Art held a retrospective of John Waters’s films. It was an event that, like many things having to do with the artist in the first two decades of his career, came with a side of controversy, as certain citizens objected to the idea that taxpayer money would be put toward such lewd material.

That was a long time ago, though, and people change. (For many, the only relic of that event was one of Waters’s most famous nicknames, the Prince of Puke, which he earned in an admiring op-ed in the Baltimore Sun.)

Now, 33 years later, the Prince has once again teamed up with his hometown museum for a retrospective. But this time, the exhibition, titled “John Waters: Indecent Exposure,” is dedicated to Waters’s visual art, taking stock of more than 160 sculptures, photos, films, and sound works produced over the past 25 years.

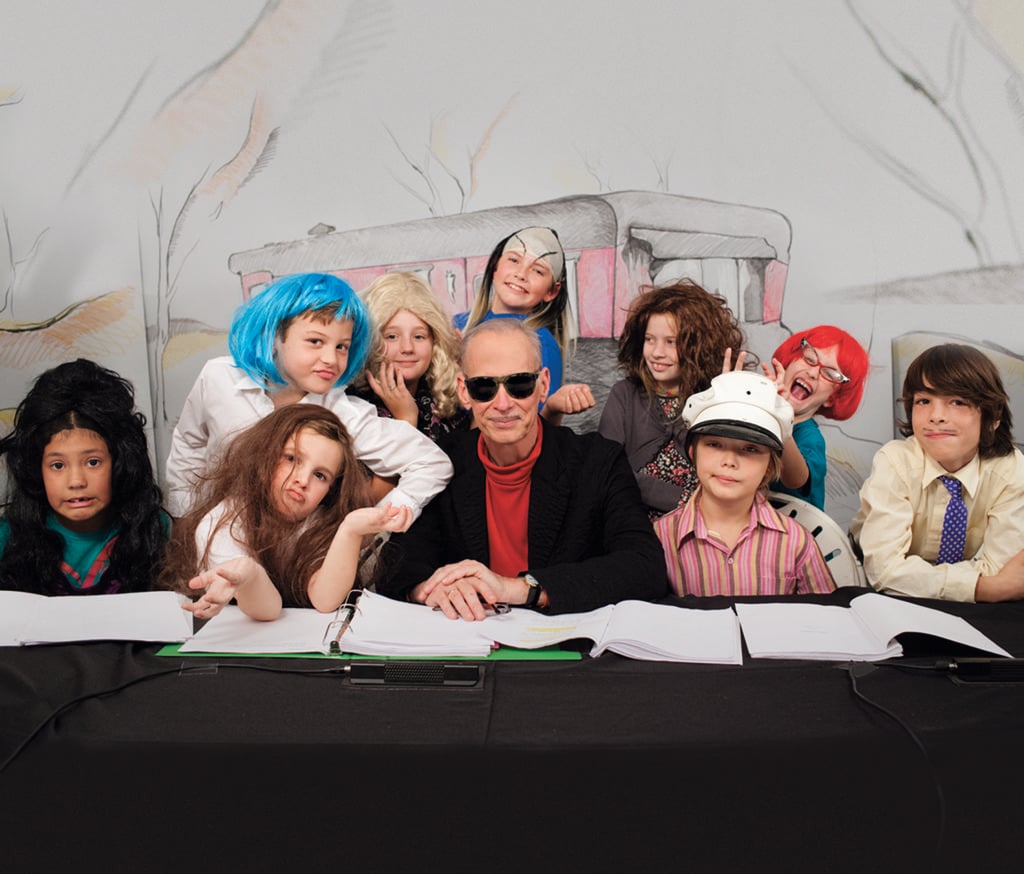

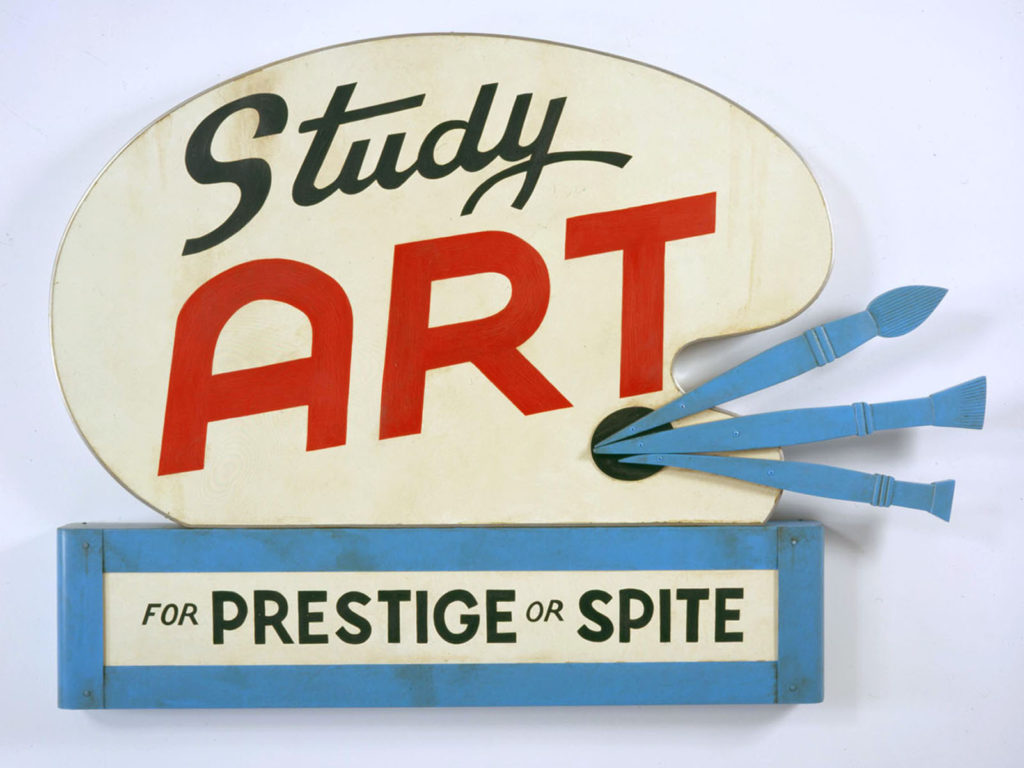

There isn’t any controversy this go around—a sign of shifting mores, perhaps—though the show is, in typical Waters fashion, a weird, witty, and tacky affair. There are classic novels reconceived as pulpy smut (Clitty Clitty Bang Bang), a tabloid boasting sensational stories about 20th-century intellectuals (“Joan Didion Hits 250 Pounds!”), and a reimagining of Waters’s iconic 1972 film Pink Flamingos with child actors (no feces-eating, thankfully). There are fetishistic film stills of old actress’s body parts (a series of shots of “Grace Kelly’s Elbows,” for instance), altered photos imagining the visages of Justin Bieber and Lassie after severe plastic surgery, and plenty of appearances from the artist’s one-time muse, Divine.

At age of 72, Waters says he’s busier than he’s ever been. In addition to the show and its attendant press events and screenings, he’s currently on tour with his annual Christmas show, hitting up 17 cities. He recently finished his newest book, a collection of essays called Mr. Know-It-All: The Tarnished Wisdom of a Filth Elder, which comes out next spring on Macmillan. And he still makes artwork often.

“I think if I slowed down, I’d probably drop dead,” he says.

A few days after the show’s opening, artnet News spoke with Waters over the phone. A message indicating that the call was being recorded played when he picked up the receiver.

“Are you in prison?” he asked with glee, before explaining that a similar message plays whenever an incarcerated friend calls. “Are you writing for the prison paper? Had I known, I would have to geared my answers in another direction…”

The rest of our conversation follows below.

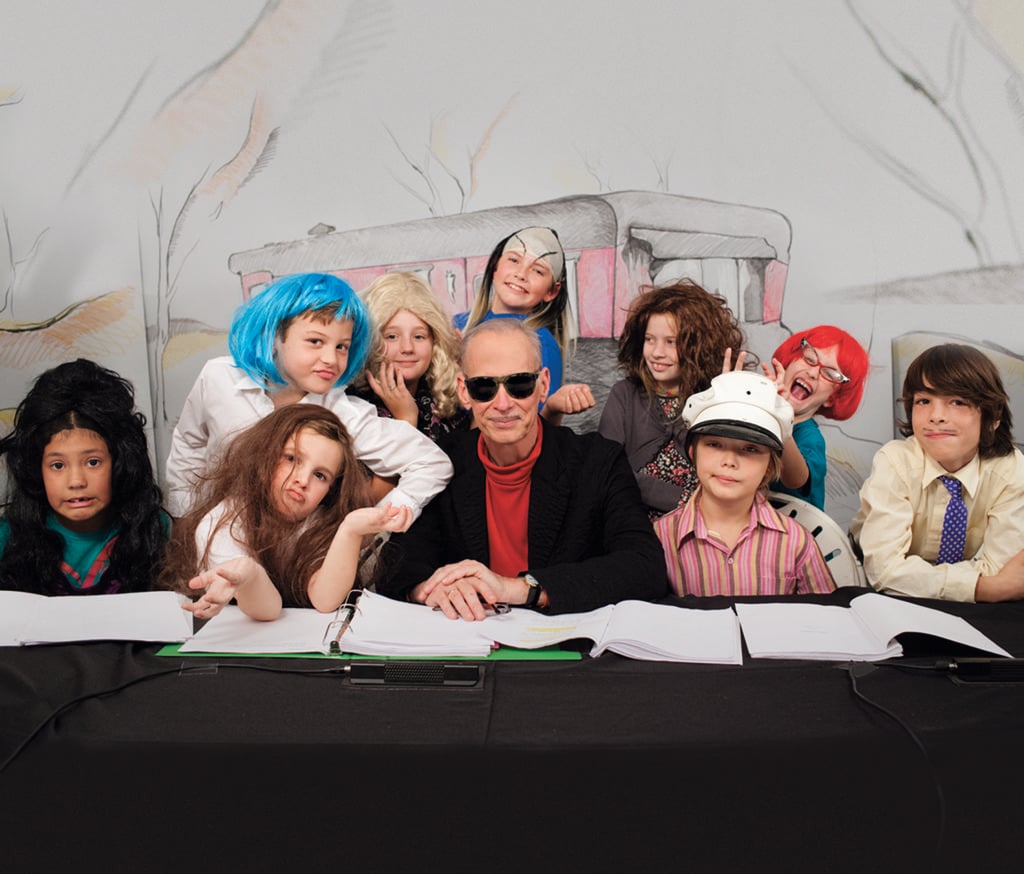

John Waters, Study Art Sign (For Prestige or Spite) (2007). Courtesy Sprüth Magers Gallery. © John Waters.

A retrospective at the biggest art museum in your hometown—did you ever imagine this growing up?

I never thought about having museum retrospectives when I was younger, but I was an ambitious kid. I got Variety. I bought an Andy Warhol print of Jackie Kennedy that was $100 in 1964. It’s still hanging in my living room. So I wasn’t naïve. I wanted New York to come discover my work, they just didn’t.

The last time the museum mounted a retrospective of your work, you got a new nickname: the Prince of Puke. There are a few puke references in the current show as well.

There’s Puke in the Cinema (1998), a collection of different shots of people vomiting in movies. Because all actors feel that, to really show their chops, they have to vomit. In old movies when, say, a woman catches her husband with another girl, she always runs into the bathroom and pukes. I’m name-dropping here, but one time I was at Cannes with Jeanne Moreau, and we watched a movie in which this happened. Jean asked, “Did you ever puke when you were upset? I never puked.” She’s right! When something bad happens, we don’t puke. I don’t, at least. But they always do that in movies. So I was celebrating that oddness.

John Waters, Puke in the Cinema (1998). Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York. © John Waters.

Have you received any backlash from the show up now?

Have I gotten a big pan? No. But there’s so few art critics left in the country now. I’ve built a career on negative reviews. That wouldn’t work now.

The exhibition takes so many jabs at the art world. I wondered if anyone took offense to that.

The pieces that are inside jokes, poking fun at the industry—that’s the work the art world likes the best. The things that they all think, but would never say out loud. Something like, “All photographs fade.” That’s not something that you hang in an art gallery. “See You in Basel, Bitch.” I’m sure a lot of them think that, but I don’t know if they voice it to too many clients.

John Waters, Art Market Research (2006). Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York. © John Waters.

One of my favorite pieces in the show is Art Market Research (2006), a hypothetical look at the feedback artists would be given if there work were subject to marketing tests.

You know, that could happen! I went through lots of marketing tests on my movies—they try to get it so that every audience would like something, which of course is impossible. If they could do that, then every movie would be a giant hit. But don’t be so surprised if one day the art world were to actually embrace this one day.

Do you have any other conjectures as to what the art world will look like in the future?

No. The thing is, all the stuff that people hate about the art world, I love. I embrace all the elitism. I think it’s hilarious. I love impenetrable art writing. I make fun of it, but I make fun of things I love. I don’t hate the art world at all. I find it fascinating. It’s a secret club; you have to learn the rules. But you learn to see in a different way. So it is a magic trick that you learn, and you are better than other people if you can see art.

The other day, I saw the most perfect thing. I was driving downtown in Baltimore, and there was a bus stop with a glass enclosure. In it was a homeless person lying on the bench, and over top of him was the ad for my show with the phrase, “Contemporary art hates you.” And I thought, “Oh, this is so great! Where is my camera?” It was the perfect shot. I thought that was pretty cool of the museum, to use a piece like that for their public ad campaign.

John Waters, Justin’s Had Work (2014). Courtesy of the Artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York. © John Waters.

There’s a long history of taboo and film, a lineage you’re certainly a part of. What do you think would be taboo in the art world today?

Oh, celebrity art—the most-hated thing. The thing that I have to run from. That’s why I use it and make fun of it in a lot of my pieces. I hate it the most too.

It’s certainly a trend right now. Here at artnet, our most popular pieces by far are the ones that involve a celebrity in the title.

The art world is very suspicious of anyone that comes in from a different career. And I get why. But they don’t mind the other way. For a while, all the artists went and made movies. I was one of the only people who went the other direction.

John Waters, (1992). Courtesy Marianne Boesky Gallery. © John Waters.

After establishing yourself as a filmmaker and public personality, did you find it difficult trying to carve out your own artistic identity?

No, because I’ve always celebrated failure. I celebrate the failure of photography, the failure of editing. I’m a failed publicist, with movies—I’d be fired in five minutes if I worked on movies. My movies that were technically the worst were the only ones that worked in the art world. The more Hollywood ones didn’t work at all.

In your mind, what are the big differences between the art world and the film industry?

Well, in the film industry you have to pretend that every single person in the world is going to love it. In the art world, if every single person in the world loved it, it would be the worst possible thing. In the art world, you only have to pretend that the smartest person in the world would like it and everybody else would hate it. I understand both quests.

John Waters. Beverly Hills John (2012). Courtesy Marianne Boesky Gallery. © John Waters.

You’re a collector as well. Do you want to talk a little bit about your collection?

No, because then it always seems like I’m bragging. Divine and I used to look through art catalogues, see the collections of some people and say, “I know where they live. We could steal that.” I always say that to the guards when I have a museum show: “I should warn you, my fans steal.” You should see their faces. They go, “What?!” I guess most artists don’t say that when they meet security teams.

I imagine you inspire a very particular breed of fandom.

Well, I had a friend who used to say that a stolen present is even more loving, because you had to risk going to prison to get it. But I have great fans. They always get my jokes. They always get their hair done before they come see me; their roots are always touched up. They give me great little presents. And now everyone’s cool everywhere. You can go to an obscure little college in the Deep South or Paris, and the audience looks exactly the same.

John Waters, Tragedy (2015). Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York. © John Waters.

You must get a lot of fan art.

I do. I have it all in my studio. A lot of them are really, really fantastic—but some are really bad. Those are the ones that steal my heart.

Many of your early films were considered taboo when they first came out. Do you feel our cultural relationship to those taboos is different now?

Well, I don’t think I’m that different. What I did in the beginning is now just American humor—it’s on television. I think it’s lovely. I didn’t have to change much, but everyone else did. I have nothing to complain about. Not one bad thing has happened to me because of my career. No one ever asks me if I went to school.

John Waters, Dorothy Malone’s Collar (detail) (2017). 1996. Courtesy Marianne Boesky Gallery. © John Waters.

I’ve read that you have a remarkable book collection. Can you tell me about some of your favorite art books?

God, I’d have to look. I have so many art books everywhere. I have one about invisible art. It’s just a guy who threw water on paper until it evaporated—I kind of like that one. I just got volume six of the Warhol catalogue raisonné. I love reading every word. It’s at the foot of my bed.

John Waters, Campaign Button (2004). Courtesy Marianne Boesky Gallery. © John Waters. Photo: Elisabeth Bernstein.

I’ve never met anyone who actually reads them like that.

Oh, it’s like a detective novel. I love to read the provenances, where they went, how they got sold each time, and who owned them. Then there’s the people who put “private collection” because they’re smart enough to know there’s people like me reading them. The other ones are just bragging.

Okay, a stock question: You’ve had this big retrospective now. What’s it like looking back?

It’s good, because you forget about everything. Once the works leave your studio, they either get sold and go to a collector’s home or they’re in storage. So I haven’t seen most of them. I think when the lights go out at night, they talk to each other. They say, “Oh, do you believe we’re in a museum?” I think I hear the blue nudes from the permanent collection scream in the other room: “No, asshole is upstaging me!”

John Waters, Jackie Copies Divine’s Look (2001). Courtesy Marianne Boesky Gallery. © John Waters.

What’s the weirdest question you’ve ever been asked in an interview?

Well, they’re usually not in interviews. They’re usually when I do my spoken-word shows. This girl said recently, “My father said he almost went home with you in a bar one night.” That was a weird one.

One last lofty question for you. Do you ever think about what your legacy will be?

All my stuff is at the Wesleyan [University] film archives. We had to decide how many years it would be after I’m dead until people could look at my personal stuff. They said, “Well, don’t make it too long because sometimes people forget.” People that were really famous when I was growing up in the ’50s and stuff, we don’t know who they are now. When Andy [Warhol] died, he was at the bottom of his career. He was not doing great, and his paintings weren’t successful. So you just don’t know how long the run’s going to be. Look at how people’s reputations change daily these days.

But it doesn’t matter, because you’re dead. The best title ever was that Bergman movie, The Silence. He meant it of the dead, and they sure are silent. How’s that for an ending?

“John Waters: Indecent Exposure” is on view through January 6, 2019 at the Baltimore Museum of Art.