Politics

‘This Painting Could Be the Future’: Artist Jonathan Harris on Why His Viral Image ‘Critical Race Theory’ Struck a Chord Around the Globe

The artist has sold over 1,000 prints of the striking image.

The artist has sold over 1,000 prints of the striking image.

Sarah Cascone

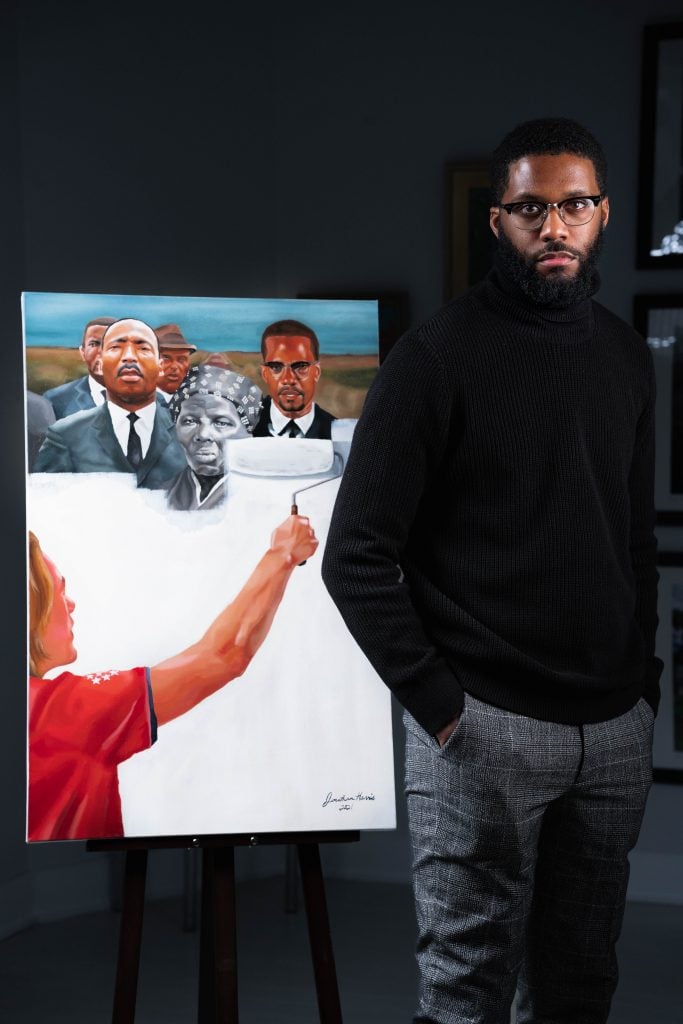

It’s a hauntingly effective image. A blonde figure stands, back to the viewer and paint roller in hand, covering up the images of Martin Luther King Jr., Harriet Tubman, and Malcolm X with strokes of white paint. Widely shared on social media, Critical Race Theory (2021) has been embraced as a powerful reminder of the importance of teaching and preserving Black history.

The canvas is the work of Detroit artist Jonathan Harris, who, since taking up painting full time nearly two years ago, has dedicated himself to making work expressing his lived experience as a Black man in the U.S. Critical race theory, which examines the ways in which racism is embedded in our nation’s legal systems and policies, has been circulating in academic circles since the 1970s. But it began making headlines, especially in conservative media, last year as some local lawmakers sought to proactively ban its teaching.

“I was hearing Black people questioning if our history was going to be in jeopardy,” Harris told Artnet News. “We only know what we are taught. My mind went to, ‘how far can this actually go?’”

That’s when the idea came to him. Three of the most famous advocates for Black American rights, their contributions to the nation’s history literally wiped out—whitewashed along with the inherent ugliness of our history of slavery, oppression, and structural racism.

Jonathan Harris, Critical Race Theory (2021). Photo courtesy of Jonathan Harris.

The vision might seem extreme, but since January 2021, 35 states have proposed measures that would limit or prohibit the teaching critical race theory, on the grounds that it is a “divisive topic,” according to Education Week. A parents’ group in Tennessee even protested that their children were reading an autobiography of Ruby Bridges, one of the first Black students to integrate an elementary school, because it documented the negative response of the white community to desegregation.

“If we don’t push back as these bills are getting passed, this painting could be the future,” Harris said.

The artist texted himself the idea for the piece in the spring, and started painting it over the summer, working on it for several months. But he never expected Critical Race Theory to strike such a chord with viewers.

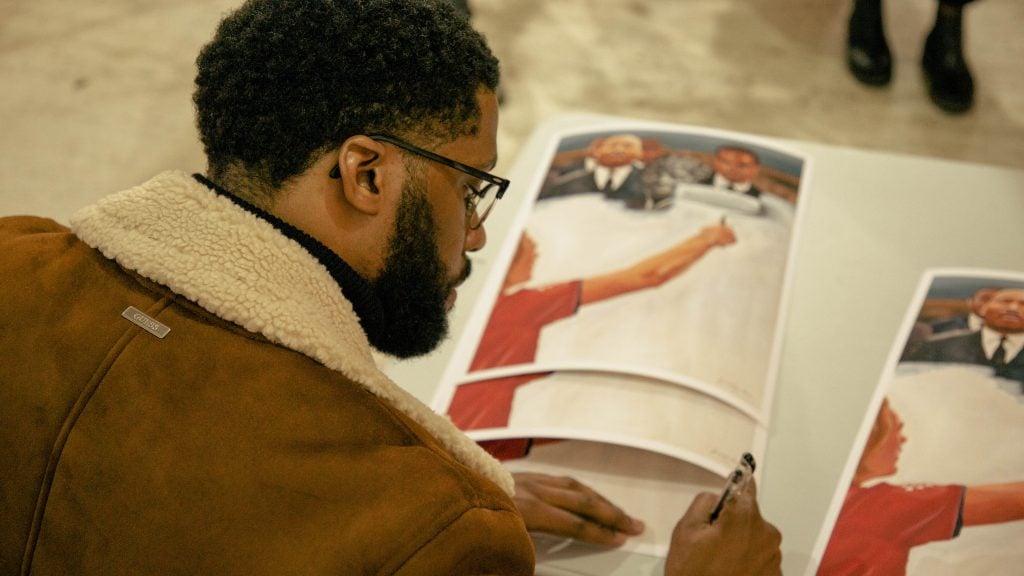

The canvas debuted in November in a three-artist show at Detroit’s Irwin House Gallery, where it sold to a private collector on opening day for an undisclosed price. The show closed November 20, but the painting’s journey was just beginning. Two days later, the political activist group “The Other 98%” shared the image on its Facebook page, which boasts 6.5 million followers. Harris quickly became inundated with messages and comments from around the world.

“It’s just really unbelievable to see that piece touched so many people,” he said. “I’ve sold over 1,000 prints all over the world, to countries I’ve never heard of.”

We spoke to Harris about his artistic background, what inspires his work, and why Critical Race Theory is such an important piece.

Jonathan Harris signing copies of his painting Critical Race Theory (2021). Photo courtesy of Jonathan Harris.

When did you start making art?

I have been drawing my entire life. As I child I was in a gifted and talented group that met after school to draw. In college, I studied graphic design and studio art. But I had never painted anything. I was just drawing and doing graphic work.

One day in 2019, I saw my cousin painting some paint-by-numbers thing, and I wanted to try it. I started to paint celebrities and stuff I had seen on Instagram that I thought people would like, just to sell it or get attention.

Then one of my friends told me I should come to the Detroit Fine Arts Breakfast Club, where collectors from the state of Michigan meet every Monday. The guy who runs it, Henry Harper, took me under his wing. He saw something in me that I probably didn’t see in myself at the time—my skills were pretty amateur then.

Henry explained to me about different types of art, and how people want to buy art that tells the stories of life. That opened up something in me, to look at life as a muse. I started to paint things that were more sincere, more honest about how I felt and life in America as a Black man.

How did you transition to making art full time?

I was working at Coca Cola in the marketing department and painting after work and on the weekends. My job gave me two weeks off at the beginning of the pandemic so they could figure out how people were going to work from home. I saw how much work I was able to produce just during those two weeks. And I was concerned about being out in the world. So I said to myself, “I can try this.”

I had a little bit saved up—not a lot, but I knew that if I dedicated as much time and energy to my art as I did to this business that wasn’t mine, I believed that it would work.

That whole summer I was just painting, selling a few works here or there to keep the lights on and put some money in my pocket.

My first show was a three-person show at Irwin House Gallery in September 2020. That got a lot of attention. The works were all acrylic and charcoal drawings. But one of my friends, Joshua Rainer, a fabulous artist, said, “If you can do this with acrylic, man, there’s no telling what you could do with oil.” So I got some oil paints and just did it every day.

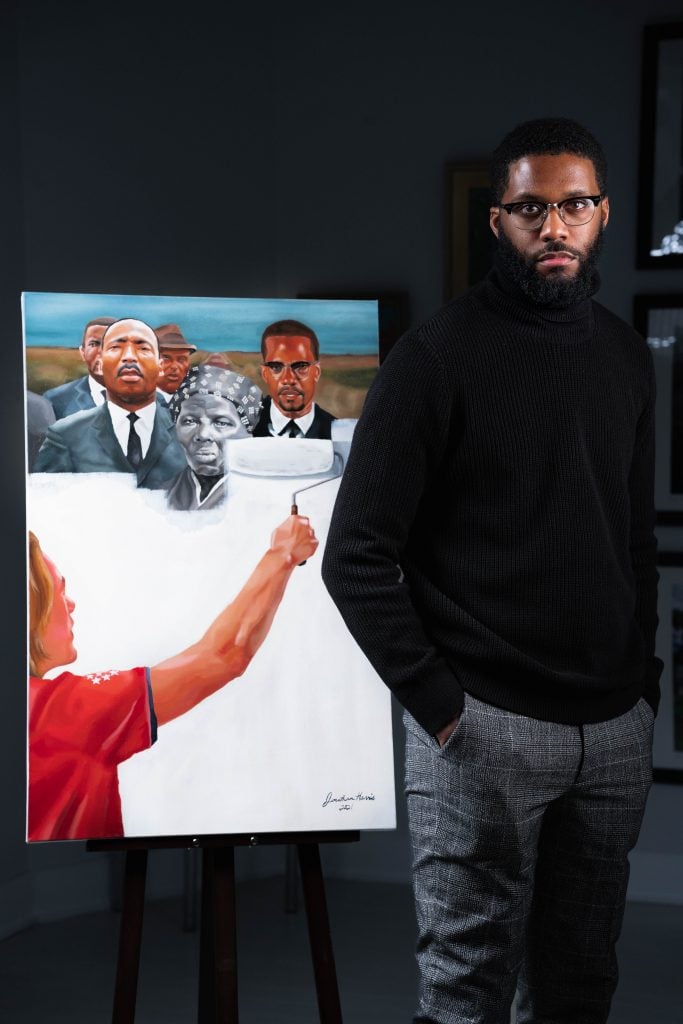

Jonathan Harris with his painting Critical Race Theory (2021). Photo courtesy of Jonathan Harris.

Why do you think critical race theory has become such a flashpoint for conservative media and lawmakers?

We live in a sensitive time. People think, “If I feel like something makes me uncomfortable, I’m going to speak about it and make it be known.” I think conservatives are trying to switch it, like, “Even though our forefathers or great-grandfathers caused this, it’s not us now. And we feel uncomfortable with you bringing this back up.”

It’s not fair, because unless you’re doing some work to make us feel comfortable, nobody’s going to feel comfortable. It’s just going to be a constant tug of war.

How did you chose the three figures that appear in the work?

The images of Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and Harriet Tubman are undeniably known across all races—or so I thought. I thought everyone would recognize them. An older white lady I know, who is part of the art group, came to the show. When she looked at the piece, she said, “This piece is so powerful. I see Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, but why did you paint Aunt Jemima on there?”

It wasn’t a joke—it was an honest question. It was just really shocking. If you don’t know who Harriet Tubman is, do you know the stories of slavery and the stories of oppression?

Jonathan Harris. Photo courtesy of Jonathan Harris.

If critical race theory is about acknowledgment and understanding of the way that systematic racism is structurally integral to our nation’s history, the risk is that to ignore racism’s existence is to perpetuate it.

Correct. It’s so deep. If you think Black people who are in the quote-unquote hood chose that, or did something to deserve it, that’s not true. In some places, Black people were not able to buy property. If you think about when segregation ended, it’s not that long ago. My parents knew that if they were going down South, there are certain areas that you can’t be in after dark, or you can’t stop at certain places to get gas. My dad saw that in his lifetime, and that’s scary. That’s just one generation away. And then think about two generations before that, what did his grandparents see? It’s not that far out.

And what if it does get to that point, 200 years from now, of, “Oh, we don’t need to teach the kids about Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, or Harriet Tubman”? What if that really is the plan? That’s why I created the piece.

If we don’t push back as these bills are getting passed, this painting could be the future.

I’ve been to therapy, and the first thing you do is talk about the past. I don’t think a therapist would say, “don’t talk about what makes you uncomfortable,” or “let’s not talk about the past, let’s just move on.” That’s not the way to heal. That’s going to make it worse.

Why is it important to you to address these issues in your work?

It’s extremely important. I’m passionate about Black people and telling our story in a way that can be understood by people who don’t look like me, so that people who do look like me are given the opportunity to shine and be ourselves, and also be in positions of power.

I tell people all the time, if I had the opportunity to just paint pots and pans and beautiful landscapes, I would do it. But I have a responsibility as a Black person in America who is conscious and paying attention to things to do more than that. So that’s what I’m going to do.