Art World

What Do Artists Mernet Larsen and Diane Simpson Have In Common? A Fascination With the 45-Degree Angle

Two exhibitions at James Cohan Gallery put the artists in dialogue.

What if we saw the world from a 45-degree angle? This topsy-turvy premise united two shows “Mernet Larsen: Thinking About Cézanne” and “Diane Simpson: 1977–1980” at James Cohan, New York (Simpson’s show is on view through March 23; Larsen’s closed on March 16), wherein sculptures (Simpson’s) and paintings (Larsen’s) playfully vacillate between two and three dimensions.

They make an intriguing dyad. Now in the late years of their career—Larsen is 84, Simpson 89—both artists have made careers as art world nonconformists—each with a unique visual language that ran outside the dominating art world narratives for decades. But even if they didn’t know it, these two artists were mining parallel fascinations. That synchronicity—and where it diverges—offers compelling thoughts on the ways these artists have devoted themselves to challenging the eye.

Diane Simpson, Chaise (1979). Photo: Phoebe d’Heurle. Courtesy of James Cohan Gallery.

“I’m just drawn to the 45-degree angle,” Simpson said in a phone call recently, “Maybe I need to be psychoanalyzed to tell you why, but that bird’s eye view is interesting to me. Mernet and I have that in common.” Simpson’s exhibition, which marks her first with James Cohan (the gallery recently announced her representation), brings together a series of elegant, cardboard sculptures made from 1977 to 1980, the years following her leap from drawing to sculpture. The works consisted of sawed cardboard sheets assembled into sculptures through a puzzle-like interlocking of forms (she uses no adhesives).

In keeping with her practice of the past 40 years, the sculptures reference everyday objects—from furniture to utilitarian architecture. One of the highlights of the show, Chaise, a chaise lounge composed of intersecting cardboard panels, meanders off the wall and into the gallery space, its planes shifting to create an ocular volleying that is common in Simpson’s work. For Simpson, her sculptures are deeply connected to the act of drawing.

Diane Simpson. Courtesy of James Cohan Gallery.

“In the late 1970s, I was making drawings of objects with a perspective that made them very dimensional. One of my professors suggested I build them,” explained Simpson, “I was working from home from my studio at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago, and I passed the Children’s Museum. In the window, there was a little cardboard chair. I thought maybe I could get some of that cardboard and start playing around with it,” she added.

Simpson notes the influences of conceptual German artists Bernd and Hilla Becher on these particular cardboard sculptures, too. Around that time, she had seen an exhibition of their photographs of industrial towers at the Art Institute of Chicago and was awed by the alluring mix of form and function. “I was blown away by the Becher photographs. These photographs that documented European industrial structures like lime kilns and cooling towers were designed by engineers with function in mind…. an unselfconscious approach that resulted in these wonderful shapes and repetitive patterns,” she explained. “The surface details were not arbitrary but were an integral part of the overall form. I feel that this interconnection of detail to the overall form is very important to me as I was making these earliest works. It has continued to be a guide throughout my work.”

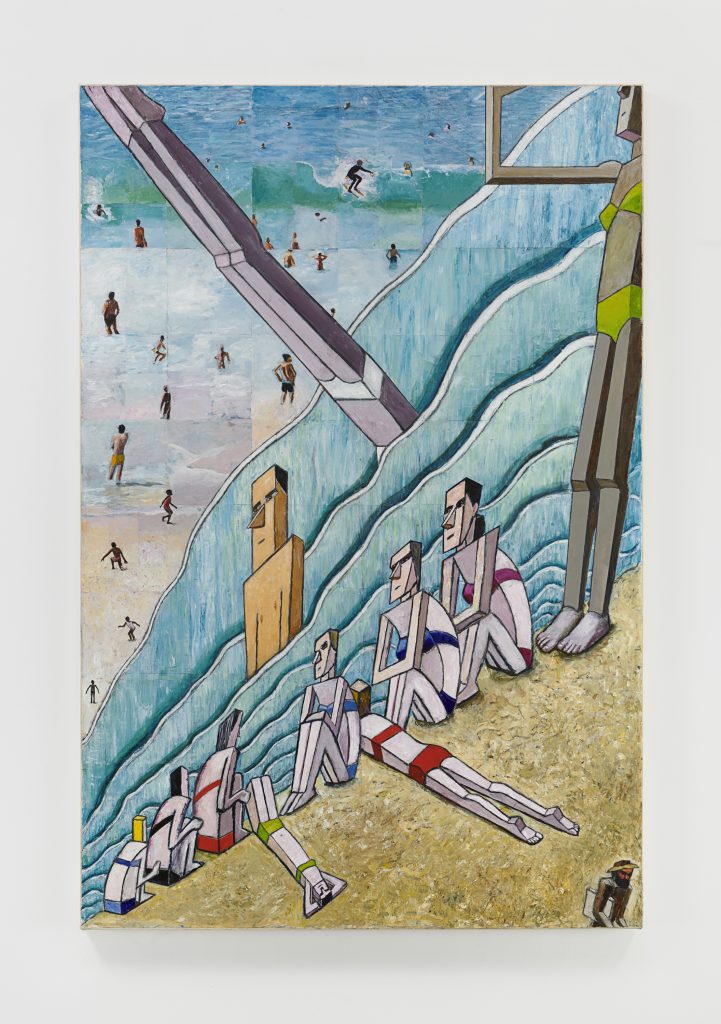

Mernet Larsen, The Bathers (After Cézanne) (2023). Photo: Phoebed’Heurle. Courtesy of James Cohan Gallery.

Larsen’s approach, meanwhile, might be thought of as an inversion of Simpson’s. Within the two-dimensional confines of her paintings, she creates an uncanny dimensionality. Larsen, who has been represented by James Cohan since 2015, is known for her distinctive hard-edged figurative style depicting a vertiginous parallel world, ripe with humor and drama. Her works can be exhilarating in their sense of disorientation.

While Simpson’s works are decades old, Larsen’s works are all new, made in the past few years. These include eight paintings and a series of related studies. As the exhibition title “Thinking About Cézanne” would suggest, in these works, Larsen mines her lifelong fascination with Paul Cézanne and her works take on the French impressionist’s most iconic imagery—his bathers, landscapes, even his famed portrait of Madame Cézanne—and extrapolate alternate possible constructions.

“In my twenties, I became fascinated with what was unique about Cézanne—I felt that he was often misunderstood in relation to Post-Impressionism. His works let your eye rove around and they never let it stand still,” Larsen explained.

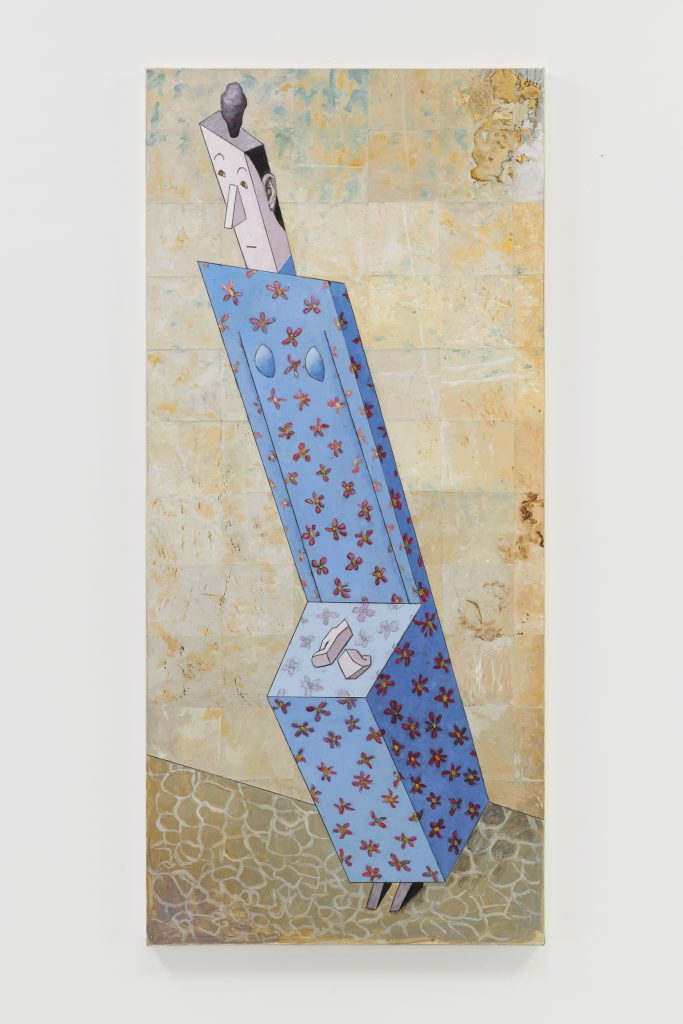

Mernet Larsen, Madame Cézanne (2022). Photo: Phoebe d’Heurle. Courtesy of James Cohan Gallery.

Larsen recalled seeing a portrait of the artist’s wife Madame Cézanne and being particularly grasped, even startled, by this off-kilter perspective of the composition. This would set Larsen into a deep dive of research on his work. Ultimately a bit intimidated by the French artist, she never directly addressed his work in her painting, as she had done with other influences. More recently, however, she looked back on his work and was surprised.

“These paintings had more normal perspective than I’d remembered … it got me thinking about what Cézanne represented. I thought it would be fun—and playful in a way—to look at his work again but now as someone having a conversation with him saying: yes, but what if we did it another way? What if we really titled the perspective.”

Mernet Larsen. Courtesy of James Cohan Gallery.

In one painting, Larsen reimagines Cézanne’s famous Bathers, but in her version the the women wear bathing suits and the waves of the ocean are piled, dizzily high, as though towers of water about to crash down—a reference to Bunraku puppet theatre. “In Bunraku theater, the puppeteers come in, walk between staged waves, ” Larsen noted of her inspiration. Another area of Larsen’s Bathers is collaged exuberantly with photographs of contemporary beaches. In these works, we seem to be hovering above the world almost as though we were standing over a dollhouse.

In another work, Cézanne’s House, the French artist’s home—from his painting House in Aix—hovers in the sky as though projected upward. The view is aerial. Farming fields can be seen in their plotted rectangles in the background. Paratroopers fall through the air surreally. The house meanwhile rest on two triangles balanced on each other. The image is freed from gravity and even the confines of a given time or place.

Installation view of “Diane Larsen: 1977–1980” 2024. Photo: Phoebe d’Heurle. Courtesy of James Cohan Gallery.

Ultimately, Larsen’s and Simpson’s are rooted in axonometric projection—a process in which a drawn shape is rotated axially away from the picture plane such that multiple sides of the object are visible at once (this is the angle, Simpson calls the “bird’s eye view.”) It’s perhaps unsurprising then that the two share a number of inspirations including Chinese and Japanese scroll paintings, Turkish and Indian miniatures, and Russian Suprematist works which incorporate these encompassing perspectives.

“There’ve been times in my life that I’ve thought about taking a turning point working more three-dimensional work, but within the confines of the painting I can return and make changes,” said Larsen of her process. “I admire Diane for the patience and deliberation it takes to make up her mind.”

When asked what she and Larsen had in common, Simpson didn’t hesitate. “We’re both abstracting forms from initially realistic sources and they’re both in a way figurative or organic, but both become in our final forms become very architectural. They have an angled orientation,” she said. “We’re both interested in the architecture of pictorial space.”