Museums & Institutions

Did Leonardo Paint a Second ‘Salvator Mundi’? An Art Historian Found Evidence Suggesting His Studio Made Two Versions

The clue lies in the drapery of Christ's sleeve.

The clue lies in the drapery of Christ's sleeve.

Sarah Cascone

Did Leonardo da Vinci’s studio paint the Salvator Mundi twice? A new study comparing preparatory drapery drawings by the artist as well as known copies of the now-infamous work—which sold for a record $450 million at auction five years ago—found significant variations in the details, suggesting Leonardo may have created two versions of the composition.

The theory comes from Martin Clayton, the head of prints and drawings for the Royal Collection Trust at Windsor Castle, reports the Art Newspaper. Clayton gave a presentation of his latest studies at “Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi Revisited,” an October conference in Leipzig, Germany.

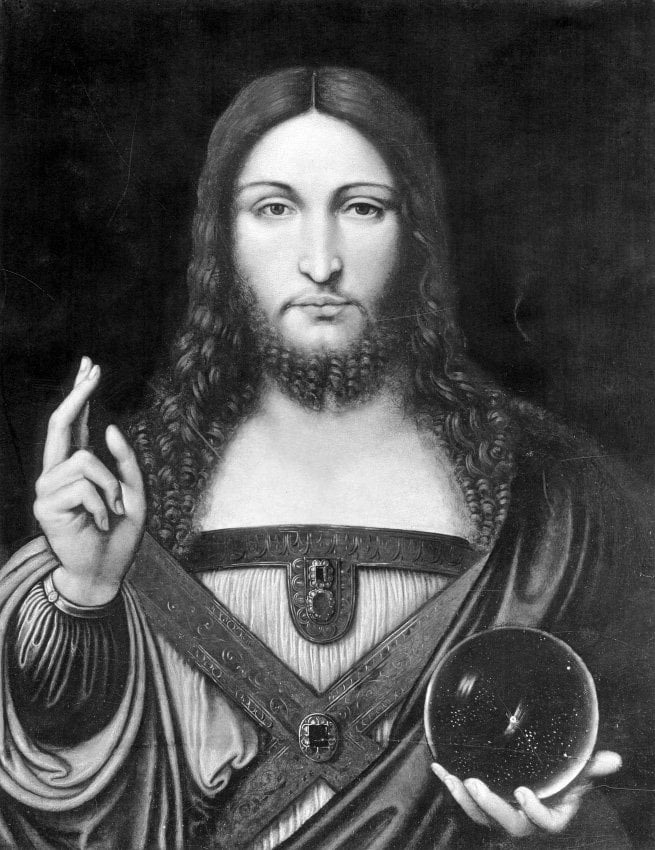

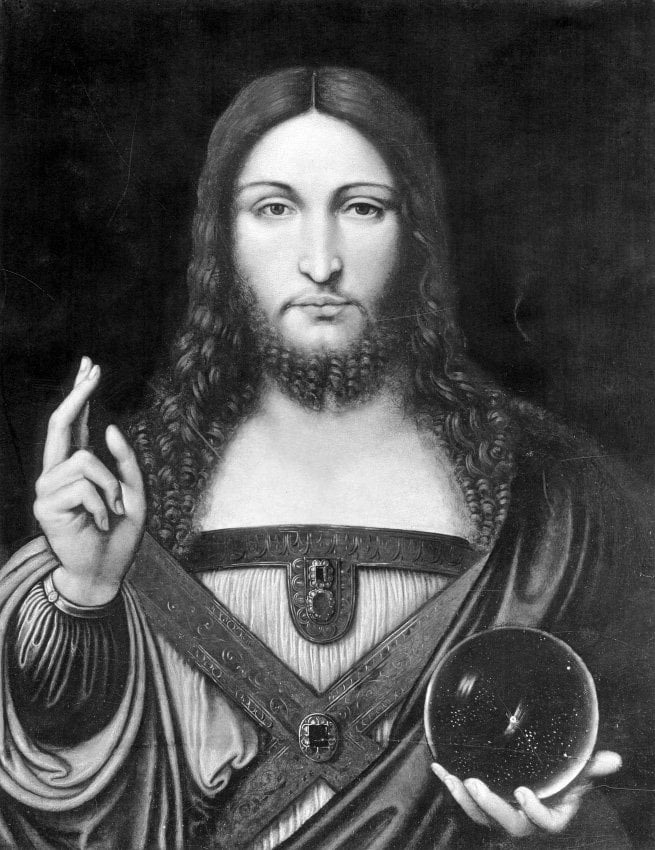

The key detail under review is the intricate drapery in Christ’s sleeve, hanging from his arm raised in blessing. In the famous version now owned by Saudi Arabia, a darker outer robe surrounds the folds of a pale shirt.

That’s also how the sleeve appears in the best-known copy of the work, the Ganay version, so named for Paris’s De Ganay collection, where it previously belonged. Other known copies—by Cesare da Sesto in Warsaw, Giampietrino in Detroit, Girolamo Alibrandi in Naples, and a lost one from Zurich’s Stark Collection—also feature a similar handling of the sleeve.

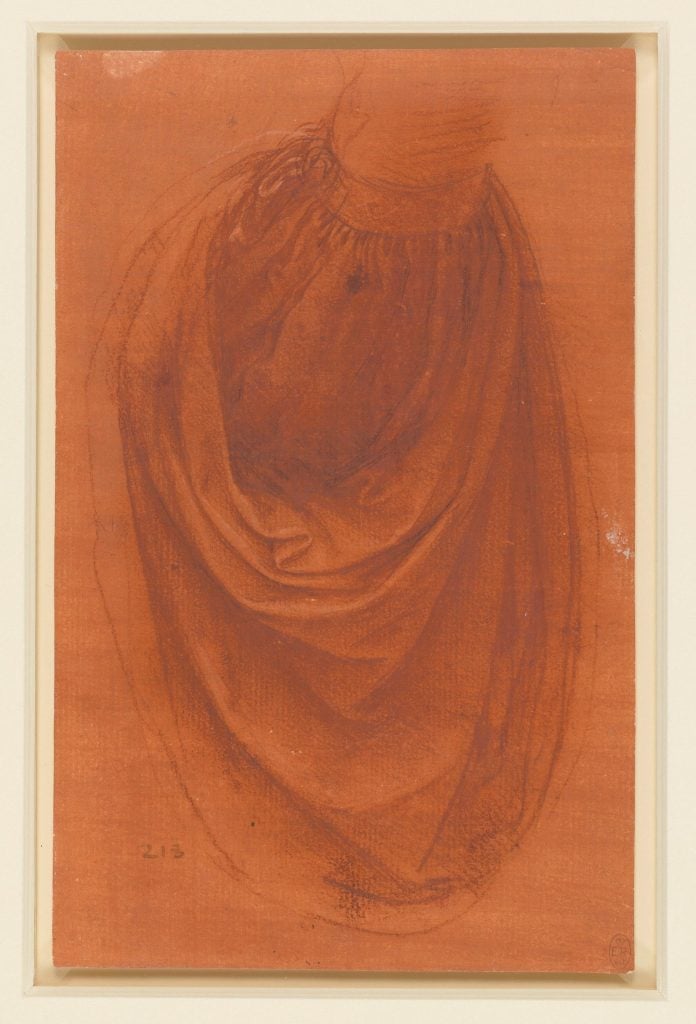

Leonardo da Vinci, The drapery of a chest and sleeve (ca. 1504–08). This is a preparatory drawing for Salvator Mundi. Courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust at Windsor Castle.

But there’s another copy, known as the Worsley or Yarborough Salvator Mundi, after the collections that once owned it. In that painting, which hasn’t been seen since appearing at auction in Rheims, France, in 1962, there is almost a puff sleeve, with a cuff at the wrist.

There are two Leonardo drawings in the Windsor collection believed to relate this area of the painting. Both are part of a group of 500 surviving works on paper that would have served as studio models during the artist’s lifetime, aiding his workshop in carrying out his commissions.

In one of the drawings, the artist includes a detail of an upraised arm, at more of an angle than the finished work, but with the folded fabric draping around the wrist. The other drawing shows the same sleeve with the cuff as the Yarbrough/Worsley Salvator, with its pleats rising vertically up to the wrist.

Leonardo da Vinci, The drapery of a sleeve (ca. 1504–08). This is a preparatory drawing for Salvator Mundi. Courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust at Windsor Castle.

Clayton’s presentation offered the possibility that Leonardo’s studio was working on two versions of the Salvator Mundi at once, varying some of the details between the works.

He also raised questions in connection with the first drawing, which also carefully rendered the fabric on Christ’s chest, including an omega-shaped fold that some art historians believe symbolizes the wounds of the crucifixion.

The omega fold is faithfully replicated in the Ganay and Yarbrough/Worsley Salvators, but difficult to discern in final painting. This suggests that later restorations—which are known to have been extensive, to the point that some experts doubt the attribution to Leonardo—could have obscured the artist’s original work in that area of the painting.

Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi (ca. 1500). Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

Art historians have noted the similarity between the preparatory drawing at Windsor and the Yarbrough/Worsley copy before.

In the 2019 book Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi and the Collecting of Leonardo in the Stuart Courts, authors Margaret Dalivalle, Martin Kemp, and Robert B. Simon dedicated an entire chapter to the drapery drawings, noting that it’s possible that the Yarbrough/Worsley copyist had seen Leonardo’s painting in an unfinished state.

Rather than painting two versions of the Salvator Mundi, the book suggested, the artist could have merely revised the sleeve, changing the folds in the drapery late in the game.