Analysis

7 Unbelievable and Contentious Takeaways From a New Documentary About ‘Salvator Mundi,’ the $450 Million ‘Lost Leonardo’

Questions continue to swirl about the world's most expensive painting.

Questions continue to swirl about the world's most expensive painting.

Sarah Cascone &

Eileen Kinsella

On March 5, 2014—less than a week after its founding—Artnet News published a short item based on a New York Times article about the sale of a recently discovered Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi, for a reported $75 million. Little did we know, in a few short years, the painting would become the world’s most expensive work of art, selling for a record $450 million at Christie’s New York in November 2017.

In the years since that initial piece, we’ve followed the story closely: from the legal dispute surrounding Salvator Mundi’s sale to Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev by Swiss dealer and Geneva freeport owner Yves Bouvier to the controversy surrounding the auction and the painting’s subsequent disappearance. The dollar value placed on the work, the issue of its authenticity, and questions surrounding its whereabouts have dominated art world headlines, captivating readers around the world.

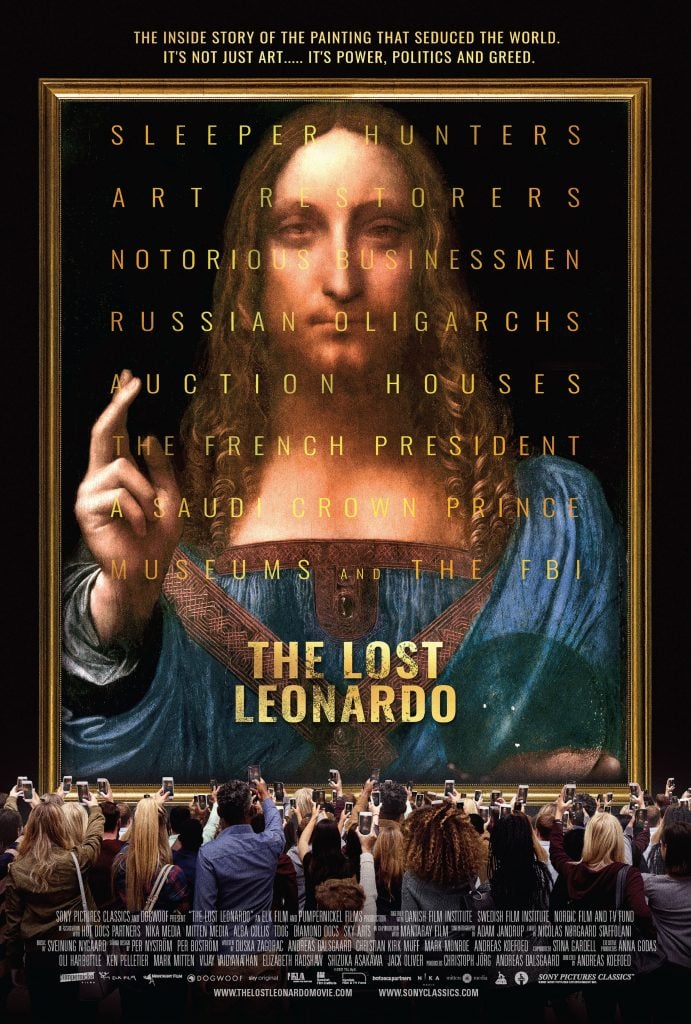

Now, the painting is the subject of The Lost Leonardo, a compelling new documentary directed by Andreas Koefoed and distributed by Sony Pictures.

The film does a superb job of weaving together the saga from the start, when the painting was discovered in 2005 at a small New Orleans auction house. The earliest comprehensive account of the painting’s journey was detailed by art historian and critic Ben Lewis in his 2019 book: The Last Leonardo: The Secret Lives of the World’s Most Expensive Painting (Ballantine).

“This is the most improbable story that has, I think, ever happened in the art market,” said Evan Beard, head of art services at Bank of America and one of the film’s talking heads.

An ingenious opening credit sequence tracks the painting as it circles the globe, its value skyrocketing from $1,500 to $450 million in just 12 years.

The painting goes on view in London, changes hands in Switzerland (via a sale brokered in Paris), and comes to auction in New York, where it was purchased at Christie’s by Saudi Arabian crown prince Mohammed bin Salman. That’s when a new wrinkle in the story develops, as Salvator Mundi drops out of sight, whisked away at the peak of its fame and notoriety.

Poster for The Lost Leonardo, directed by Andreas Koefoed. Photo courtesy of Sony Pictures.

“The mystery is sort of solved, but not really,” says an unseen news reporter as the film fades out over a sweeping view of the New York City skyline. The scene concludes an exhaustive series of dozens of interviews—in New York, London, Paris, cities in Italy, and Berlin—with the people who came in contact with Salvator Mundi over the past 15 years, or were privy to its history and the debates that raged around it.

The film raises compelling questions about restoration, expertise (and the associated responsibilities), authenticity, and the madness and opacity of the international market. Yet another film about the painting, titled The Saviour for Sale and directed by Antoine Viktine, premiered on French television in April and is slated to open in the U.S. on September 17.

Here are seven choice quotes from The Lost Leonardo that caught our attention and reflect the thorny issues at hand.

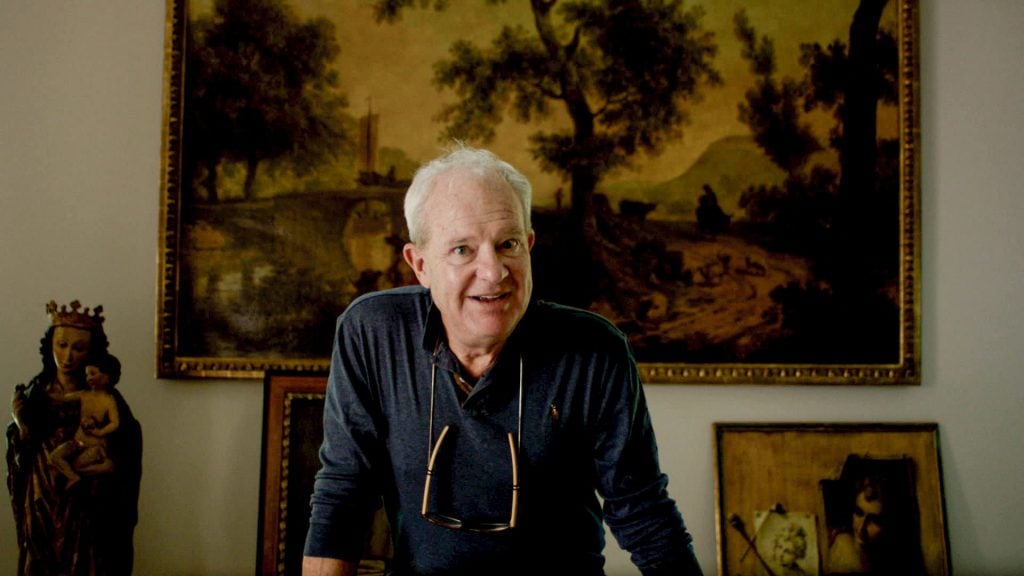

Dealer Alexander Parrish spotted the Salvator Mundi at a New Orleans auction. Film still from The Lost Leonardo. Photo courtesy of Sony Pictures.

The picture came in a cardboard box, which is kind of what you would expect for the sort of money we spent.

—Alexander Parrish, art dealer

Art dealer Alexander Parrish spotted the painting for sale in 2005, at a New Orleans auction house that identified it only “after Leonardo.” He acted on a hunch, acquiring it with Old Master dealer and expert Robert Simon for just $1,500.

Both men thought Salvator Mundi was a “sleeper”: a painting that “is clearly by a much better artist than the auction house has recognized,” Parrish said. “A sleeper hunter is someone who looks for these mistakes.”

Simon and Parrish couldn’t have known it at the time, but the purchase marked the beginning of the painting’s unlikely ascent into the stratosphere.

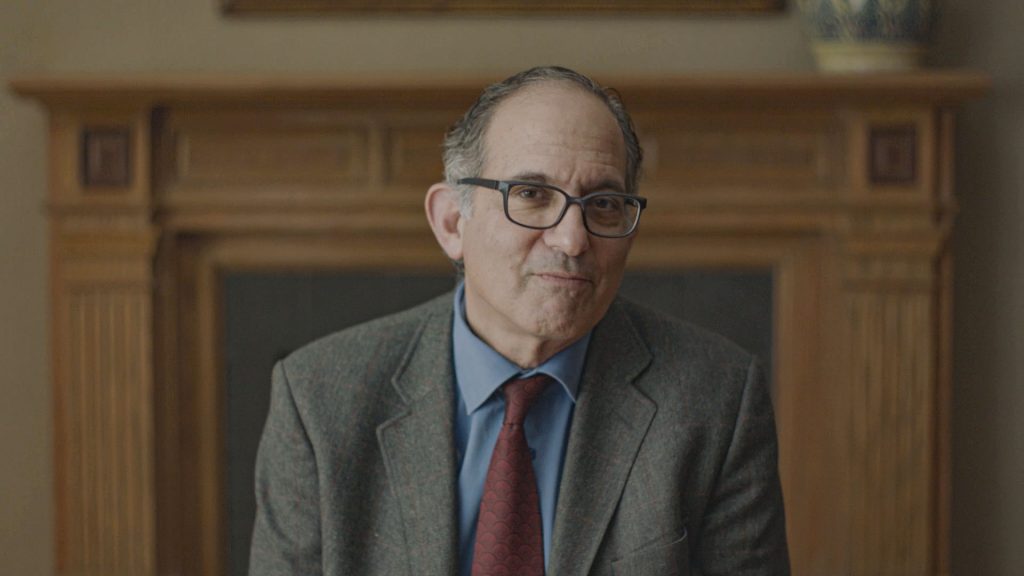

Dealer Robert Simon purchased the Salvator Mundi with Alexander Parrish from a New Orleans auction. Film still from The Last Leonardo. Photo courtesy of Sony Pictures.

My hands are shaking. No one except Leonardo could have painted this picture.

—Dianne Modestini, conservator

Realizing that the roughly 500-year-old painting had sustained damage and heavy-handed restoration work over the years, Parrish and Simon hired expert Dianne Modestini to examine and restore the painting. (Absurdly, given its future price tag, they brought it to her in a black plastic garbage bag.)

Her initial impression was that “there are very lovely passages, and other passages are very damaged, overpainted.” The first hint that the painting is not a mere copy is a pentimento showing that the thumb was originally positioned differently.

Then, after months of work, a subtle detail convinces Modestini that this is something even rarer: “There is a transition in this area from the lip to the upper lip that is imperceptible. There is no line there for the edge of the lip—it’s exactly what is present in the same area in the Mona Lisa.”

But with just 15 known Leonardo paintings in the world, such an attribution was an extraordinarily bold claim.

“To say I have found a [Leonardo] picture is akin to saying you know, ‘I had a spaceship on my lawn and I saw some unicorns,’” Parrish admitted. “It’s just so far-fetched, don’t even try to convince yourself it’s right, because you’re just going to look like a fool.”

Maria Teresa Fiorio, a Leonardo expert from Milan, was invited to view the painting Salvator Mundi at the National Gallery in London. She denies having authenticated the work, later shown there as an autograph Leonardo. Film still from The Lost Leonardo. Photo courtesy of Sony Pictures.

Nobody asked me a formal opinion about this painting.

—Maria Teresa Fiorio, Leonardo expert from Milan

After Modestini finished her restoration, Simon reached out to Luke Syson, then a curator at the National Gallery in London, about the potential Leonardo discovery. Syson asked to see it in person, and arranged to have five experts on the artist come for a viewing at the museum in 2008.

In 2011, the work went on view at the museum with a wall label identifying it as a rediscovered Leonardo—a move that remains controversial a decade later. But did the art historians and scholars at the National Gallery really authenticate it?

That’s the million-dollar—or hundred-million-dollar—question at the heart of the film.

“I didn’t really get an answer. I didn’t get a direct answer. I also knew not to insist,” Simon, who was there, admitted. But about a week later, he claims he got a call from the museum saying that “basically everyone had agreed that the painting was indeed by Leonardo.”

But Maria Teresa Fiorio, one of the experts on hand, claims she never authenticated the work. And even Martin Kemp, who was also part of the viewing and remains one of the painting’s most steadfast defenders, acknowledged that “expectations are dangerous, because you end up by seeing what you want to see.”

“Everybody wanted it to be a Leonardo, so everybody took the most optimistic view of it as they could as a Leonardo,” London-based art reporter Georgina Adam said. “And perhaps it is a Leonardo.”

New York magazine art critic Jerry Saltz—perhaps Salvator Mundi’s biggest detractor—took a more cynical view: “Everybody was complicit in dreaming up this beautiful dream of a lost Leonardo da Vinci.”

When pressed by the filmmakers, Syson insisted he had no regrets about his role in legitimizing the world’s most expensive painting. “You’re not going to get anywhere,” he said.

Dianne Modestini restored the Salvator Mundi and stands by her belief it is an authentic Leonardo. Film still from The Lost Leonardo. Photo courtesy of Sony Pictures.

You have the old parts of the painting which are original—these are by pupils—and the new parts of the painting, which look like Leonardo, but they are by the restorer. In some part, it’s a masterpiece by Dianne Modestini.

—Frank Zöllner, German Leonardo expert and author

Modestini’s careful work repairing and restoring the cracked wooden panel ultimately became a source of controversy.

“The joke circulating around the contemporary art world was that that painting was a contemporary painting because 90 percent of it had been painted in the last 10 years,” dealer and Artnet News contributor Kenny Schachter said.

Frank Zöllner, a Leonardo scholar in Germany, said that he thought that the best-preserved parts of the painting, including the hand and the hair, look like they were painted by a pupil of Leonardo, and that the area that is most skillfully done is “exactly the part that has been restored.” In the effort to return the work to its former glory, he opined, Modestini had “overdone it a bit.”

“I can’t paint like Leonardo,” Modestini countered. “It’s very flattering, but it’s absurd.”

Further complicating matters was Modestini’s financial interest in the painting. She called rumors that she was a part owner “completely untrue,” but acknowledged that her contribution went beyond restoration, helping secure the attribution and serving as a Salvator Mundi spokesperson.

“I said to Robert one day, ‘I’m not sure what to charge you for this, because it’s more than just a restoration.’ He said, ‘When we sell it,’ he said, ‘I’ll give you what, you know, I believe you deserve,’” Modestini said. “He paid me generously.”

Auctioneer Jussi Pylkkänen fields bids for Salvator Mundi during the postwar and contemporary art evening sale at Christie’s on November 15, 2017 in New York City. Photo by Eduardo Munoz Alvarez/Getty Images.

Jesus is not an easy sell.

—Alexander Parrish

So says Parrish at the start of the film upon the painting’s initial discovery. And for a time, he might have been right. He and Simon spent years unsuccessfully trying to sell the painting for $200 million, with institutions in Boston, Houston, and Dallas all ultimately passing.

“It was a very frustrating thing,” their third partner, Warren Adelson, said. “I had the rarest painting in the world by the greatest artist in the world, and I couldn’t sell it.”

But thanks—in no small part—to one of the most hyped-up marketing campaigns ever seen in the auction world, the numbers ultimately proved Parrish wrong.

In an ingenious move by Christie’s, the painting was branded the “male Mona Lisa,” drawing a parallel between Salvator Mundi and Leonardo’s most famous portrait. A slick promotional video didn’t show the painting at all, instead focusing on the enraptured faces of viewers, including actor and art collector Leonardo DiCaprio.

The auction house’s strategy was to “convince the potential buyer that you’re now buying a celebrity that will play into the power and prestige of your acquisition” Beard, of Bank of America, said.

And it worked: “It was the trophy to end all trophies,” journalist Alexandra Bregman said.

The record-breaking sale is all the more remarkable given that Jesus is one of the prophets in Islam, and religious scholars typically forbid that the prophets be depicted in art.

“It’s a sacrilegious painting,” said New York Times reporter David Kirkpatrick, who was the first to reveal Bin Salman as the buyer.

Yves Bouvier flipped Salvator Mundi for an enormous profit. Film still from The Lost Leonardo. Photo courtesy of Sony Pictures.

It’s common sense. You buy low and sell high.

—Yves Bouvier, freeport magnate and art dealer

Before the painting hit the auction block in 2017, Yves Bouvier made an outsize profit on the Salvator Mundi, acquiring it for $83 million from Parrish, Simon, and Adelman in a deal brokered by Sotheby’s. That same day, Bouvier sold it to Rybolovlev for $127.5 million—a $44.5 million markup.

“It’s extraordinary and quite frankly extremely unheard of in the art world” Adam, the London art journalist, said.

The freeport magnate had initially tried to discourage the purchase. “Don’t buy this painting—it will never be a good investment,” Bouvier warned Rybolovlev, noting the pre-restoration condition issues. “It’s like selling a car that has been in an accident.”

But in the end he was happy to conduct the sale, driving up the price by inventing fake negotiations with the sellers in email exchanges revealed in the film. Bouvier falsely told Rybolovlev that the buyer was asking for as much as $150 million.

This was “just a business game,” Bouvier said. “I was nice because he was ready to pay $130 million.”

Nevertheless, Rybolovlev was furious when he found out. In total, the Swiss dealer made $1 billion in profits on a group of 37 artworks he sold the Russian, who claimed to have been defrauded.

Of course, it’s hard to feel too bad for Rybolovlev, considering he ultimately sold Salvator Mundi for $450.3 million, pocketing the $400 million hammer price. So we’re talking about a profit of roughly $273 million here, a fact which the film inexplicably does not note.

Meanwhile, after years of legal battles surrounding the dispute, Bouvier claims to “have lost everything,” but looked remarkably content showing off his out-of-left-field unicycling skills to filmmakers.

The crown prince of Saudi Arabia, Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud, and French president Emmanuel Macron at the Louvre Museum in Paris, France, in 2018. Photo by Bandar Algaloud/Saudi Kingdom Council/Handout/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images.

If the Louvre says it’s an autograph Leonardo, that is a big deal. It’s not just art history, it’s world politics.

—Art Newspaper editor Alison Cole

In 2018, Salvator Mundi almost became the centerpiece of a blockbuster Leonardo exhibition at the Louvre in Paris celebrating the 500-year anniversary of his death. Ahead of the show, Bin Salman visited the museum with none other than French president Emmanuel Macron. The painting is said to have been there too, for a secret technical analysis at the Louvre laboratory.

Ultimately, the picture was not included in the exhibition because the owner “refused to lend it,” the film reveals. The loan fell apart because Bin Salman “wanted it opposite the Mona Lisa as a civilizational masterpiece,” Beard said.

The Louvre came so close to showing the painting that it even produced a book on its technical findings. A few copies got out, showing that the museum ultimately confirmed the work was by Leonardo’s hand—but the Louvre has refused to acknowledge its contents, with a spokesperson telling investigative journalist Antoine Harari, “We didn’t publish such a book. I think you understand it was connected to the loan. The loan didn’t happen.”

Though Bin Salman has never publicly admitted to owning the painting, possessing Salvator Mundi is certainly a form of soft power—and the film questions whether political dealings between France and Saudi Arabia could have influenced the Louvre’s opinion on its authorship.

“It’s difficult to know what to believe when you’ve got a lost painting, a lost book, and no access to the scientific examinations themselves,” Cole said.

The debate around the picture may never be resolved, but the uncertainty almost adds to its allure, especially the longer it stays hidden from public view.

“My greatest regret,” Modestini said, “is that it did not go to a museum. And, of course, everyone’s idea of the picture is now formed by mystery and legend and speculation.”