Art World

Diego Rivera’s ‘Flower Day’ Celebrates the Struggle of Post-Revolutionary Mexico—Here Are Three Things You Might Not Know About It

This seemingly quaint image is brimming with political symbolism.

![Diego Rivera Mexico, 1886, Flower Day [detail] (1925). Image by Keith Daly, via Flickr. Diego Rivera Mexico, 1886, Flower Day [detail] (1925). Image by Keith Daly, via Flickr.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2020/08/diego-rivera-flower-day-detail-1024x768.jpg)

This seemingly quaint image is brimming with political symbolism.

![Diego Rivera Mexico, 1886, Flower Day [detail] (1925). Image by Keith Daly, via Flickr. Diego Rivera Mexico, 1886, Flower Day [detail] (1925). Image by Keith Daly, via Flickr.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2020/08/diego-rivera-flower-day-detail-1024x768.jpg)

Katie White

Mexican artist Diego Rivera casts a long shadow on the history of 20th-century art, capturing the energy of post-revolutionary Mexico with a style that improbably fused four influences: Aztec culture, Cubism, Renaissance frescos, and socialist realism.

Among his many stylized pictures of working people, flower vendors are among his most famous subjects. Flower Day (Día de Flores) from 1925 was his first-ever depiction of a theme that reappeared often in his work throughout the 1930s and ‘40s.

At first glance, Flower Day reads as a quaint depiction of Mexican street life: an Indigenous woman with a basket of calla lilies strapped to her back stands at the center of the canvas, eyes downcast; two women kneel before her. Yet this famous image has many interesting layers.

Here are three facts about Diego Rivera’s Flower Day that might change the way see it.

Flower Day holds an important place in Rivera’s rise to international art stardom: it was the first major painting by the artist to enter a public collection in the United States. It was, in effect, his calling card north of the border.

The work was acquired by the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art (the parent institution of LACMA) after winning first prize in the museum’s influential First Pan-American Exhibition of Oil Paintings in 1925. “It turned out to be an important event for the art world of Los Angeles,” remarks the museum, “and also for the museum’s collection.”

Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo with Anson Conger Goodyear, then president of the Museum of Modern Art, upon the artists’ arrival in New York in 1931. Courtesy of Getty Images.

From this launchpad, Rivera attained incredible influence. During a series of trips to the US between 1930 and 1940, he would complete large-scale frescos in Detroit, New York, and San Francisco (SFMOMA is planning a sprawling winter 2021 exhibition devoted to Rivera that will include his famed Pan American Unity mural). He was treated as a celebrity, feted by the powerful, and courted as a spokesperson for radical causes. He was the second-ever artist to have a show at the recently opened Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Some left-wing critics would knock Rivera’s flower vendor paintings as trading in sentimental folkloric stereotypes of Mexico. But, on the strength of his success, he would help inspire a movement towards public art in the Depression-era United States during the New Deal.

There’s a straight line between Flower Day‘s celebration of the labor behind an aesthetic object—flowers—and the new status of art in the United States, where it had previously been considered pretty dandified. Rivera helped give art a new symbolism, both as connected to working people and as a form of dignified work itself, epitomized by his 1931 mural at the San Francisco Art Institute, The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City.

Students gathering below Diego Rivera’s famous mural at the San Francisco Art Institue. Image by Gary Stevens, via Flickr.

During his years traveling and studying in Europe during the Mexican Revolution, Rivera immersed himself in Modern art circles. For a time, he even adopted a Cubist style. But it was the majesty and scope of Renaissance murals seized his imagination, inspiring him as one of the “Tres Grandes” of Mexican Muralism.

A staunch atheist who once called religion “collective neurosis,” Rivera was not interested in the religious content of Renaissance art, but in how it conveyed didactic narratives to the masses. Even in the smaller, traditionally scaled Flower Day, we see Rivera quietly reworking religious tableaux to elevate the everyday person.

Compositionally, Flower Day has similarities to Renaissance altarpieces. Compare it to the central panel of this crucifixion by a Renaissance artist Rivera adored, Paolo Uccello.

Paolo Uccello, The Crucifixion (probably mid-1450s). Image courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The figures flanking the central flower seller in Rivera’s work clearly echo the figures flanking the suffering Christ—which makes you see that the strap at the center of Flower Day clearly mirrors a cross, conveying a message about the nobility of the suffering worker.

Perhaps in the repeating pattern of blossoms around the woman’s head there is even an echo of the repeating gold-haloed heads arrayed around a central figure in an early Renaissance altarpiece like Duccio’s Maestà Altarpiece.

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Maestà Altarpiece (ca. 1308–1311). Collection of Siena Cathedral.

Rivera employed these religious allusions in other depictions of flower sellers. In the equally famous Flower Carrier (1935), a man struggles to get on his feet under the weight of an enormous basket of flowers strapped to his back.

Diego Rivera, The Flower Carrier (1935). Courtesy of SFMOMA.

Compare it to the classic iconography of Christ Carrying the Cross.

Sandro Botticelli, Christ Carrying the Cross (ca. 1490). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Though Flower Day‘s calla lily symbolism has been interpreted as celebrating indigenous labor and customs following the Mexican Revolution, it’s worth noting that the calla lily is not an indigenous Mexican plant—it comes from Southern Africa. Its introduction is a product of colonization.

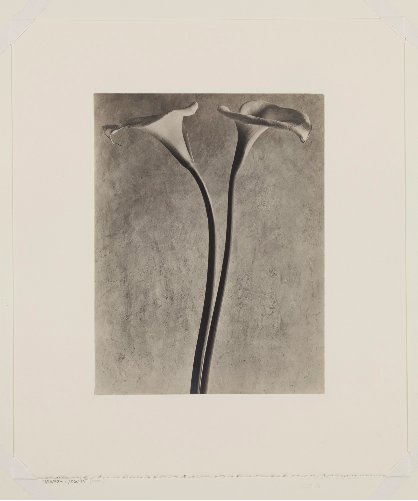

Tina Modotti, Calla Lilies (ca. 1927). Image courtesy Detroit Institute of Arts.

With its elegant petals and prominent stamen, the calla lily became the quintessential Art Deco and modernist flower. “In the early 20th century, the calla lily enjoyed a heightened popularity, particularly in the 1920s and ’30s, as dozens of painters and photographers of varying reputations and approaches to image-making made it the subject of their work,” reports one book on Georgia O’Keeffe (an artist who would later encourage Rivera’s wife, Frida Kahlo).

Innumerable famous images of the flower from the era emerged from the likes of O’Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, Edward Steichen, Imogen Cunningham, and Tina Modotti, almost always focused on its stylish form or its sexual symbolism.

Rivera himself used the flowers that way in 1943’s Portrait of Natasha Zakólkowa Gelman.

Diego Rivera, Portrait of Natasha Zakólkowa Gelman (1943). Image via Wikiart.

As for Rivera’s 1925 flower vendor, you might think of it as not just a commentary on the conditions of the Mexican masses, but as an international dialogue with his Modernist contemporaries, given their use of the theme: what looked like the height of desirability and luxury, it says, was built on the backs of others.