Art History

Is Seurat’s ‘La Grande Jatte’ the Most Misunderstood Painting of the Modern Era? Here Are 3 Facts That Cast a New Light on This Sunny Idyll

Look closer and darker themes emerge.

Look closer and darker themes emerge.

Katie White

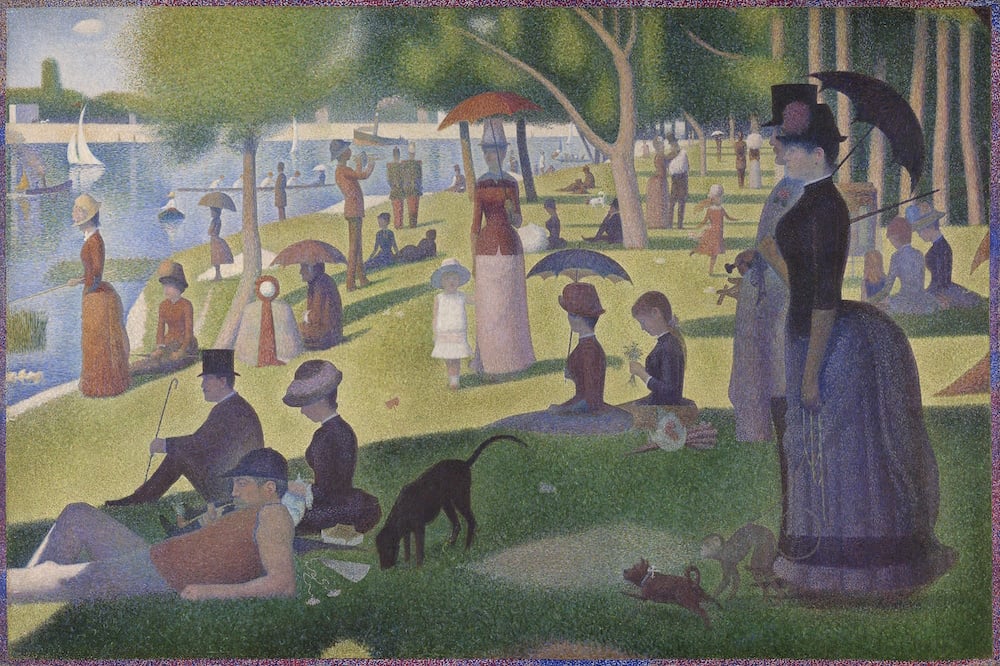

Georges Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte is a painting defined by its ambiguities. The monumental canvas, measuring some 7 by 10 feet, shows upper- and middle-class Parisians partaking in a day of leisure on La Grande Jatte, a slender portion of an island in the Seine River, located just beyond Paris. While ostensibly a scene celebrating life’s idyllic pleasures, with families reclining by the water on a warm spring day, the painting counterintuitively exudes a profound sense of desolation. The figures appear frozen in time, isolated from one another, their distinguishing facial features obscured—mere mannequins of life.

Georges Seurat, Study for “A Sunday on La Grande Jatte” (1884). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

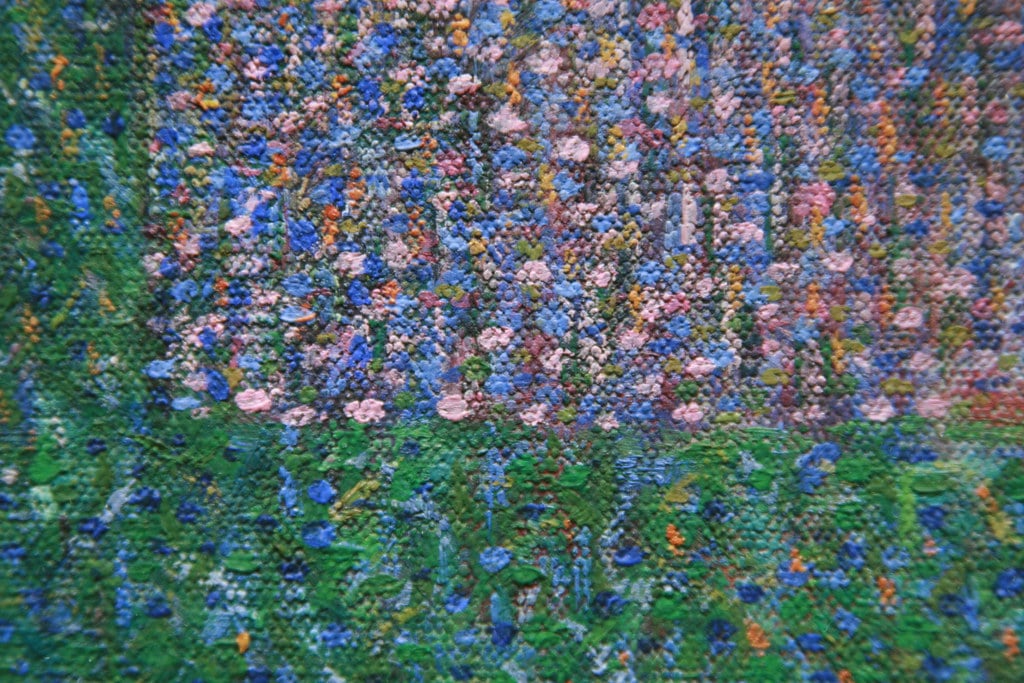

Beginning in 1884, Seurat labored over the painting exhaustively, making dozens of sketches and oil studies en plein air, then continuing work on the canvas for many months back in his studio. La Grande Jatte made its public debut in 1886 at the 8th annual (and final) Impressionist exhibition in Paris, two years after Seurat had started it—and he would continue to rework it for years that followed (more on that below). From the start, its reception was divided: some hailed it as painting’s next step forward, while others were put off by the lack of emotion or narrative. Viewers mainly puzzled over Seurat’s unusual and innovative technique employing small dots of color applied side by the side—which, while distinct when viewed up close, visually coalesced into a vibrant and cohesive image when viewed from a distance. While this style is today known as Pointillism (a term critics of the time actually coined as one of derision), Seurat referred to his own approach as Divisionism.

A quiet, intelligent, and scientific mind, Seurat had developed his technique in keeping with his studies of the latest optical and color theories—particularly those of chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul and physicist Ogden Rood—who had hypothesized that two chromatically pure pigments placed side by side would maintain a greater visual intensity than when blended together. While these theories would later be largely disproved, Seurat’s masterpiece does visually boggle, engaging the eye in a vacillation between the painting’s perceived depth and its highly worked surface.

Detail of a butterfly in Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884).

The painting has been interpreted as revealing the essence of modern existence and its double-edged sword of social spectacle and isolation. A butterfly hovering in the middle left of the painting reinforces this reading. A symbol of fragility, during the Industrial Revolution the butterfly was used in art as motif for the environmental and social consequences of progress. Indeed, this scene of bourgeoise leisure had only recently been enabled by the factory life existing just beyond the painting’s frame. The painting, which has been in the Art Institute of Chicago since the 1920s, continues to fascinate modern audiences, making pop-culture cameos in The Simpsons and a famously pivotal scene in the classic enjoy-your-life film Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.

Despite its ubiquity, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte still maintains an air of impenetrable mystery. With summer just around the bend, we decided to take a closer look at Seurat’s most famous work and pinpointed three facts that might help you to see it in a new way.

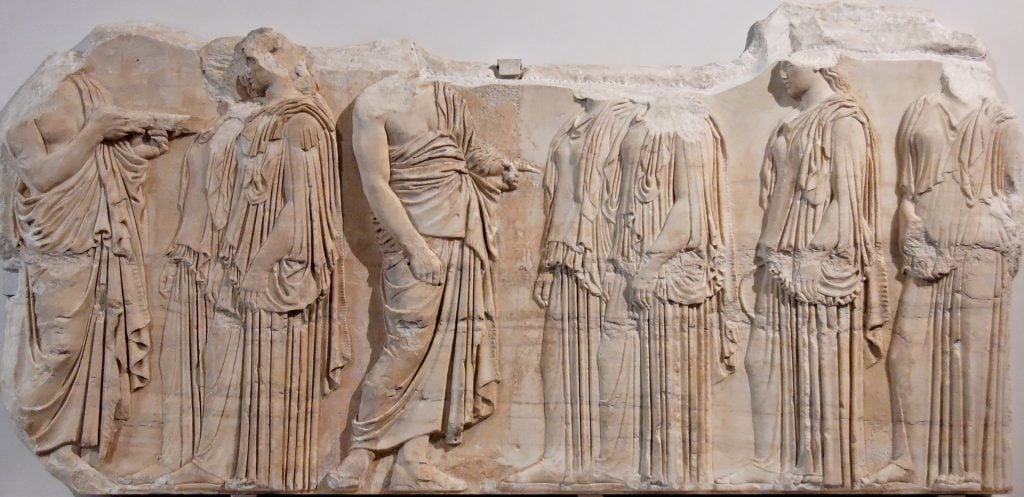

Ergastinai (“weavers”) block, from the east frieze of the Parthenon in Athens. (ca. 445–435 B.C.E.

Georges Seurat was only 27 years old when he unveiled La Grande Jatte at the 8th annual Impressionist exhibition, and the painting articulated his stance as a Neo-Impressionist—that is, he shared the Impressionists’ interest in scenes from daily contemporary life, but diverged in other aspects. Rather than striving to capture the sense of spontaneity and immediacy prized by many Impressionists, Seurat imbued his works with a monumentality and solemnity inspired by classical sculpture—values rooted in Seurat’s traditional education.

He had studied at Paris’s École Municipale de Sculpture et Dessin, followed by the École des Beaux-Arts, where he followed a conventional academic training, often copying Old Masters and drawing casts from classical sculptures. Though Seurat dropped out of Beaux-Arts after a little more than a year, he carried forward an interest in antiquity, remarking that he wanted the figures in La Grande Jatte to appear as the modern equivalent to figures on the Parthenon friezes. “The Panathenaeans of Phidias formed a procession. I want to make modern people, in their essential traits, move about as they do on those friezes, and place them on canvases organized by harmonies of color,” he explained to the French poet Gustave Kahn.

Georges Seurat, Bathers at Asnières (1884). Collection of the National Gallery, London.

In 1884, the year Seurat began studies for La Grande Jatte, he completed another monumental and pivotal work in his oeuvre, Bathers at Asnières (1884). This is a painting with which La Grand Jatte shares both insightful similarities and some very pointed differences.

For context, Sundays were a day of rest in 19th-century French society, when people across classes would escape the hustle and bustle of city life by whatever means they could. Geographically, Asnières lies on the left bank of the Seine, directly across from the island of the Grande Jatte.

In Bathers at Asnières, Seurat depicts slightly larger-than-life working-class figures in repose along the riverbank. Their dress hints at their social standing—bowler hats and straw hats were often worn by laborers—as does the industrial landscape visible in the background, which lets us know we are near a contemporary city, not some edenic milieu. And, lastly, it is the relaxed, naturalistic poses of the figures that tells us they are working class.

In La Grande Jatte, Seurat’s figures appear stiff and almost robotic, whereas here the less-clothed bodies are fully at ease in the environment—swimming, even. And whereas the men, women, and children of La Grande Jatte are shrouded almost uniformly in shadow, here, light bathes the subjects’ faces. In many ways, Bathers at Asnières is more idyllic, in keeping with the mythical bathing scenes emphasizing pleasure, than its counterpart from just two years later.

Just as fashions offer clues into Bathers at Asnières we see them playing an equally important, though distinct, role in La Grande Jatte. In the wake of the Industrial Revolution’s textile boom came the rise of ready-to-wear clothing. Just as the Asnières bathers’ garb identifies their social standing, so too do new fashions sported by the subjects of La Grande Jatte. While obviously at a more well-to-do locale, the figures at La Grande Jatte are more diverse in their socio-economic statures than a quick glance might suggest. For example, in the left foreground, the reclining man in a cap and sleeveless vest is likely a laborer, given his informal dress. The scene of ostensible leisure also becomes, with a more nuanced gaze, a place of commerce and exchange. The island itself was well known to be frequented by prostitutes, and the two women shown fishing at the riverside are likely of a lower class—identifiable by the activity itself; they are likely trying to “catch” a man. Many have argued that the woman shown walking with a monkey on a leash is likely a prostitute out with a wealthy married man, the monkey being a longstanding symbol of lust. What Bathers at Asnières portrays frankly in terms of class, La Grande Jatte purposefully muddles. In the most direct gesture, Seurat has cut off from view the very same industrial scene visible in Bathers, which would have been seen from La Grande Jatte as well.

Detail of the painted border Seurat added to the composition.

In 1889, a few years after completing La Grande Jatte, Seurat re-stretched the canvas and made an addition: a border of Pointillist dots surrounding the whole of the composition. Around this, he secured a pure white wooden frame, similar to the one the painting is now displayed in at the Art Institute of Chicago. The artist’s decision to frame the work with dots of color is, in a sense, a lens through which we are meant to view the work itself. In her seminal essay “Seurat’s La Grande Jatte: An Anti-Utopian Allegory,” the art historian Linda Nochlin argues that Seurat was the first Post-Impressionist artist to communicate the experience of modern existence through the creative process itself. She writes: “In these machine-turned profiles defined by regularized dots we may discover coded references to modern signs, to modern industry with its mass production, to the department store with its cheap and multiple copies, to the press with its endless pictorial reproductions. In short, there is a critical sense of modernity embodied in sardonic decorative invention and in the emphatic, even over-emphatic, contemporaneity of costumes and accouterments.”

Seurat, in Nochlin’s view, had landed on a technique inherently tied to the modern experience—one that abandoned the gesturalism of craft and instead allied itself with science and to industry. In this way, Seurat presaged the elimination of the artist’s hand seen decades later in the work of Andy Warhol and many others. The “notorious dotted brushstroke” that distinguished Seurat’s painting from its Impressionist peers, Nochlin concludes, “constitutes the irreducible atomic particle of the new vision.”