Art World

What Does the Remarkable Shortlist for the 2017 Sobey Art Awards Say About the Changing Canadian Art Scene?

More diverse than ever, the year's shortlist for Canada’s most prestigious art award is dominated by women. But is it enough?

More diverse than ever, the year's shortlist for Canada’s most prestigious art award is dominated by women. But is it enough?

Sara Brown

The Sobey Art Award is one of the most coveted prizes in Canada, comparable in status and sum to UK’s Turner Prize. Over the years, the distinguished art prize has included now-household names among its finalists, such as performance artist Terence Koh in 2008, and multimedia artist Jon Rafman in 2015. Last year, Jeremy Shaw—a 2017 Venice Biennale artist—nabbed the prize.

“It has become a platform to evaluate the scene, to honor the artists, look for quality, and stimulate the careers of artists,” Adam Budak, chief curator of collections and exhibitions at the National Gallery in Prague, who is the international juror this year, told artnet News. “It has become something of a prestige and it mobilizes artists.”

His statement is by no means an exaggeration. For instance, the late Canadian Inuk artist Annie Pootoogook was invited to be a part of documenta 12 in 2007, on the heels of her winning the Sobey Award the previous year.

In addition to providing an immense boost to an artist’s career, this year’s Sobey Award offers a larger sum of money than ever before: the prize money has been increased to $110,000, with $50,000 going to the winner and $10,000 to each shortlisted artist. And that shortlist for the award’s 2017 edition claims to “highlight diversity”—but what does that really mean?

Divya Mehra, Without You I’m Nothing (Eating the Other), (2015). Collection of the Royal Bank of Canada, Photo: Karen Asher. Courtesy Sobey Art Award

Two Indigenous artists have been shortlisted, and four out of the five spots showcasing one artist from each region of the country are held by women. “The country is so diverse, language-wise and geographically,” says Budak, “This complexity makes the whole situation very exciting.”

According to the award’s press material, the list focuses on artists who question and challenge preconceived ideas around diversity, identity, and performance. These include Ursula Johnson, whose work reflects her Mi’kmaw First Nation heritage and interrogates outdated ethnographic and anthropological approaches to understanding Indigenous cultural practices. Raymond Boisjoly is an Indigenous artist of Haida descent; working to delimit the work produced by Indigenous artists, Boisjoly’s practice concerns “the deployment of images, objects and materials in, and as, Indigenous art.” Divya Mehra, who works between New York, Winnipeg, and Delhi, examines constructs of “diversity” and the effects of colonization and racism.

Bridget Moser, Freak on a Leash, (2016). Production still from performance at Western Front. Photo: Ben Wilson

Performance artist Bridget Moser works with awkwardness and humor in her practice, with spoken monologues that draw from prop comedy, experimental theater, absurd literature, and intuitive dance. And lastly, Jacynthe Carrier explores the performative body in relation to its environment in videos and photographs that reimagine spaces her subjects inhabit.

“When I was making the long list, I decidedly chose to put forward only women artists,” says jurist Jenifer Papararo, executive director of Plug In ICA, who presided over Canada’s Prairies and Northern Territories regions. “My knowledge wasn’t broad enough to truly represent such a vast region, so I set terms for myself which were gendered, and beyond that I was interested in selecting artists who were engaging with making systemic changes in knowledge systems from identity politics to economics.”

The jury’s tone falls in step with the climate surrounding issues of identity politics and post-colonialism at a time branded by heightened political strife for women and minorities. This year also marks Canada’s 150th birthday, where large and contentious celebrations have been met with heated opposition from Indigenous communities and others, many rallying under the movement “Resistance 150.” Overall, it is a significant time in which institutions and government are working to reconcile deep gaps that continue to exist in Canada’s contemporary art scene and beyond.

Ursula Johnson, Hot Looking, (2014). Photo: Michael Wasnidge. Courtesy Sobey Art Award

Farther afield, indigenous perspectives gained visibility at large international exhibitions this year. At the Venice Biennale, Australian artist Tracey Moffatt was the first solo Indigenous artist to represent the country in its pavilion, and Canadian artist Kananginak Pootoogook was included in the Arsenale’s “Viva Arte Viva” exhibition. At documenta 14, Canada’s Beau Dick’s colorful masks were an unmissable highlight.

In her reflection on the shortlist, Erin Silver, a Canadian historian of queer and feminist art and assistant professor at the University of British Columbia, told artnet news, “I hope that this recognition also reflects a broader, concrete commitment to structural change in our institutions and policies, in board and jury compositions; and in enduring and genuine support and opportunities for Indigenous artists, artists of color, diasporic artists, artists with disabilities, women artists, and queer and trans artists working in this country.”

But despite its slant towards female representation this year, the award still has a long way to go: Since its inception in 2002, only three women have won (perhaps this year the scales will tip a bit further towards a balanced representation?). And what about age? This past March, the Turner Prize made the major decision to consider artists of all ages, and indeed two of its finalists are over 50, something the Sobey Art Award has yet to do (its age limit is currently 40). It’s perhaps also time to ask whether the award should take note from its Commonwealth neighbor and follow suit.

“I think this very brave and courageous decision of those who are behind the Turner Prize inspired organizers of all other prizes,” says Budak. “The organizers of the Sobey Art Award are discussing over and over whether the age limit should function over the other criteria.”

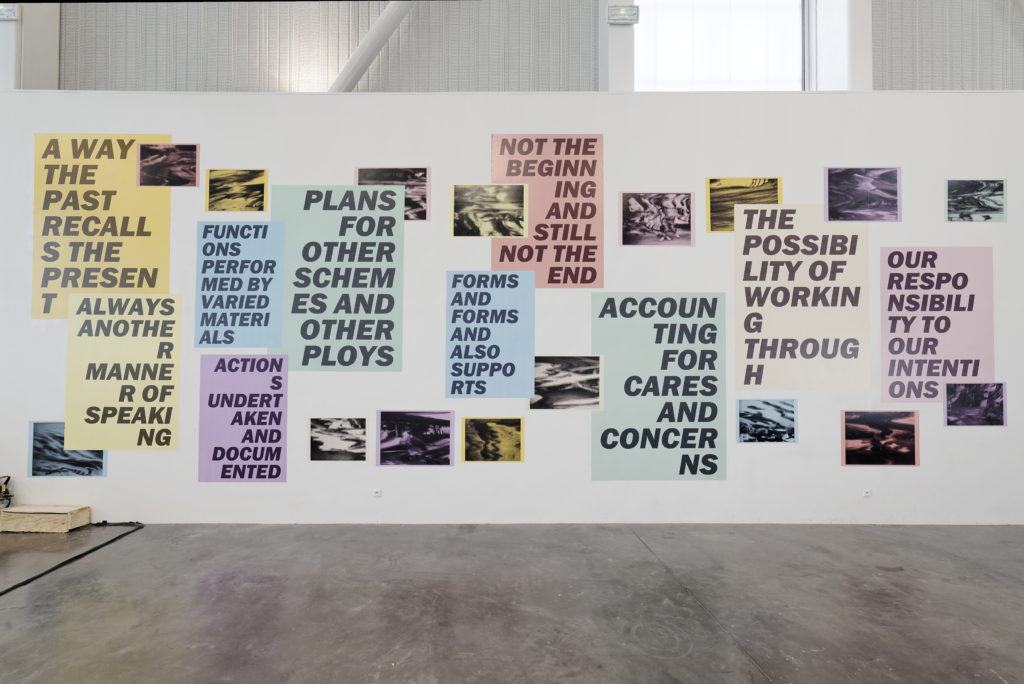

Raymond Boisjoly, Author’s Preface (2015). Installation view at Triangle France, Marseilles. Courtesy of Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver Photo: Aurélien Mole.

Encapsulating the award’s efforts towards inclusiveness in the context of a young country that is still establishing its position within the international art scene, Budak adds “I think the prize is developing itself and reflects on itself from one year to another; it searches constantly for its own identity.”

The work of the five shortlisted artists will be exhibited at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto from October 24 to December 9, 2017. The winner of the 2017 Sobey Art Award will be announced on October 25.