People

See the Strange, Haunting Final Paintings of 11 Famous Artists, From Michelangelo to Toulouse-Lautrec

A new book by Bernard Chambaz explores the meaning behind an artist's last work.

A new book by Bernard Chambaz explores the meaning behind an artist's last work.

Eileen Kinsella &

Caroline Goldstein

What can we learn about an artist from his or her final work of art? French historian and poet Bernard Chambaz thoughtfully mines this rich subject in a new book, The Last Painting, a deep dive into art history and a meditation on life and death. He highlights the lives of artists stretching back hundreds of years, ranging from Old Masters to Impressionists, all the way through the recent past, with examples by contemporary artists such as Cy Twombly and Zao Wou-ki.

As Chambaz notes: “There are no rules, and there is certainly no justice. Death can come at any time, regardless of age or how healthy you are. Some painters died in their thirties, others well into their eighties; some as the result of an accident, such as Signorelli falling from his scaffolding, others for reasons foreseen, such as Cézanne, racked by diabetes.”

Most of the book’s 100 entries are limited to a single page, yet each is packed with thought-provoking and often touching details about the lives and practices of some of our most revered artists. Here are some of the works highlighted in Chambaz’s book.

The last fresco ever executed by Michelangelo (1475–1564) was the result of a commission by Pope Paul III, who asked the master to paint the Pauline chapel in the Vatican. This work (along with a second painting, The Conversion of Saul) was widely viewed as disappointing by audiences at the time. Afterwards, Michelangelo, at the age of 75, grumbled to Giorgio Vasari, the author of The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, that painting—and fresco painting in particular—is “not an art for an old man.”

Chambaz writes that the dominant feeling in this final painting by Spanish master Diego Velázquez (1599–1660) is one of “somnolence.” The paint had barely dried on this picture when Velázquez was appointed by the Spanish King to organize a journey to the Pyrenees. But soon after, weakened by the trip, he began feeling ill and died shortly after his return to Madrid.

Johannes Vermeer, A Young Lady Seated at a Virginal (around 1670).

“Vermeer can still amaze us with this young woman’s face, which fills us with both melancholy and music, this suspended moment, the bow within arm’s reach,” Chambaz writes. Around the same time this painting was made, Vermeer (1632–1675) was at financial ruin, and a sense of decline sent the artist into “a fatal frenzy.” When he died, he left behind 11 children, having already buried three. “Then,” Chambaz writes, “for two centuries, he is universally forgotten.”

Theodore Gericault, The Left Hand (1824).

Jean-Louis André Théodore Géricault (1791–1824) had a “morbid habit” of buying amputated limbs from the morgue, Chambaz writes. He would keep the limbs at his house for weeks while he painted these anatomical fragments. “At the very end,” Chambaz says, “he waves goodbye to the world with this hand.” Géricault died eight hours after this work was done, at six in the morning on January 26, 1824, aged 32.

“Life hasn’t been too kind to him: at the age of seventeen, he lost his mother, two sisters, and brother, drowned in freezing water,” Chambaz writes of Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840), whose last sepia depicts an owl atop a coffin against a barren landscape. Though the grave has been dug, it is out of sight and the grave diggers have left their shovels in the foreground. The significance of the owl is multifaceted: they are sometimes said to have the power to see the deceased in the afterlife, and the Romans believed an owl in broad daylight signified imminent death.

After pausing work on this painting in 1836 to devote time to other paintings, John Constable (1776–1837) returned to it with fervor, despite battling a rheumatoid fever. He took particular care with the children playing on the low wall in the foreground, “bound up with memories of his childhood,” Chambaz writes. On February 17, 1837, Constable wrote to a friend saying: “It is, and shall be, my best picture.” Having finished the painting, his heart failed shortly afterwards, on March 31. The painting was presented at the Royal Academy and remained in Constable’s family for the next 40 years. His grandson sold it in 1878 for £2,200.

Edgar Degas, Two Dancers Resting (1898).

Two Dancers Resting is Edgar Degas’s (1834–1917) “final lap”, Chambaz writes. By age 65, blindness forced the Impressionist painter to abandon painting in oil, leaving him to work only in pastels and charcoal. This work is the culmination of those final efforts, done on chamois paper with a yellow background.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, The Admiral Viaud, or Paul Viaud in an Admiral’s Costume (1901).

Having suffered a miserable year in 1900—one marked by sickness, hallucinations, and pain—Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901) spent the summer of 1901 on Arcachon Bay on the Southwest coast of France with his friend, Paul Viaud. Weakened by a stroke, Toulouse-Lautrec retired to his mother’s chateau, where he began work on this, the largest picture he ever painted. As Chambaz writes: “He provides his friend with an English admiral’s uniform, an eighteenth-century wig and—quite ironically—a red nose, since he was incapable of drinking as much as a glass of wine.” The artist died on September 9, at the age of 36.

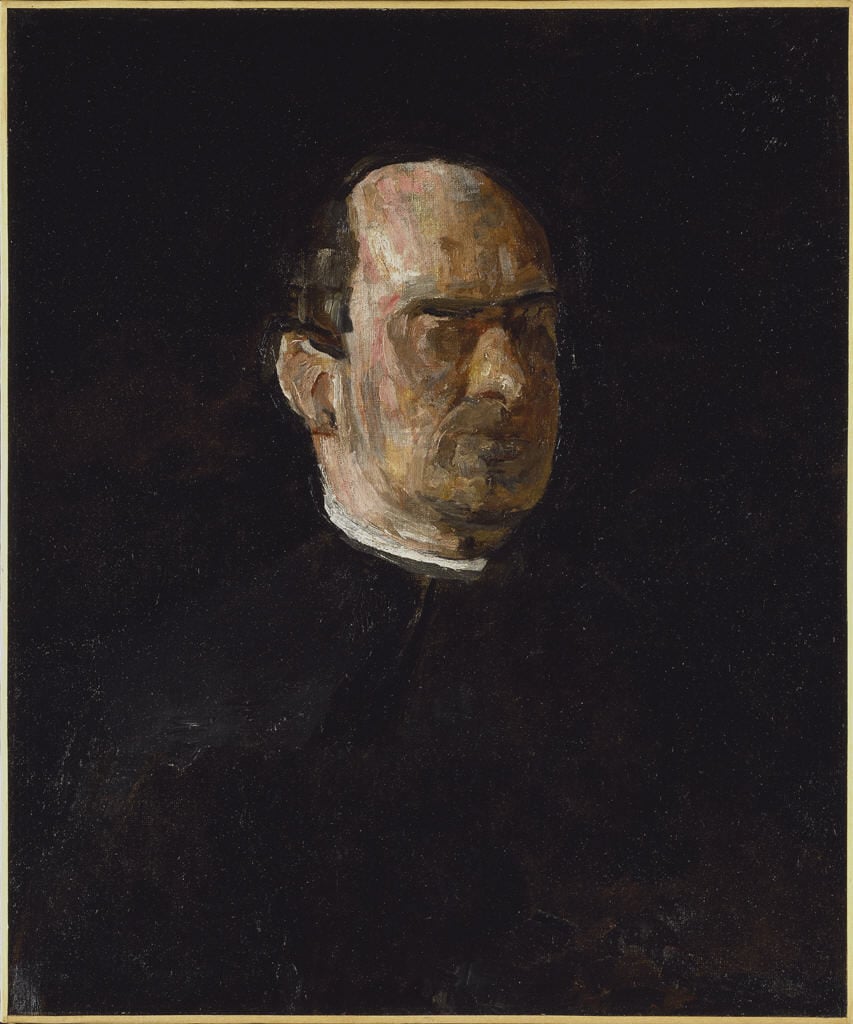

Thomas Eakins, Portrait of Dr. Edward Anthony Spitzka (around 1913). Courtesy of Creative Commons.

Towards the end of his life, Thomas Eakins (1844–1916) was losing his eyesight and relinquishing hopes of being recognized, despite some attention from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which offered in April 1916 to buy one of his paintings. Eakins, however, wished the museum would buy a larger work, and two months later he died and was cremated in secret. The subject of his creepy, unfinished portrait, Dr. Edward Anthony Spitzka, was an anatomist who carried out an autopsy on the brain of the assassin of President McKinley.

“So often a painter of absence, here he depicts a presence, but it is the presence of those who are about to disappear,” Chambaz writes of this final work by Edward Hopper (1882–1967). The picture, which is said to depict the artist and his wife, Jo, was finished shortly before his death at age 84. Interestingly, this painting was once owned by Frank Sinatra and has a recent market record: Sotheby’s sold it at auction this past November for just under $12.5 million with premium.

In perhaps the most poetic exit of this list, Mark Rothko (1903–1970) set the terms of his own demise with this final work, which was found just feet away from where the artist committed suicide in 1970.

The Last Painting is published by Acc Art Books and retails for $50.