Art World

What Is Your All-Time Fantasy Exhibition? We Asked 14 Art-World Heavyweights

A show of "new work" by Eva Hesse? Why not!

A show of "new work" by Eva Hesse? Why not!

Artnet News

At the turn of the New Year, artnet News posed a question to a few leading curators, artists, museum directors, and gallerists: What show would you like to see—impossible or not—in 2018? Some longed for the return of long-deceased artists, while others imagined computer-generated shows. See their dream exhibition ideas here in part one of our two-part series.

Jerome Caja’s Untitled (ca. 1990). © Estate of Jerome Caja, courtesy of SFMoMA.

Show: A Jerome Caja retrospective

I’d love to see the first retrospective of Jerome Caja—legendary San Francisco-based performance artist, painter, and sculptor who passed away from complications of HIV in 1995. His performances included frequent appearances as a drag go-go dancer at queer night clubs like Club Uranus, and his object making, too, relied on many of the same make-up tools. Instead of oil or acrylic, he used eyeliner, lipstick, nail polish, and glitter. Instead of canvas, he used bottlecaps, ashtrays, and pistachio shells. They’re tiny, exquisite things.

Stan Brakhage, still from Dante’s Quartet (1987) Canyon Cinema: Film.

Show: “Film Tunnels” (an experimental presentation of experimental films)

There is one dream idea I have that might work. Imagine if all the continents, in a mix of urban and remote locations, could be brought together in a single exhibition. Picture a tunnel—perhaps a disused railway line, an underpass that goes nowhere, an emergency exit from a secure building. Pick a number: 1,000. Imagine if a simultaneous, non-chronological history of experimental film took place in all these tunnels over 1,000 hours. The tunnels would offer perfect conditions: protection from the rain, the sun; the architecture would restrict light and, in places with complicated political climates, offer safety. Over this 1,000 hours in one year, the program would show films in different languages and from different timeframes. Each one would explore how perception can be recalibrated. Entrance would be free. The seats would be comfortable (but not so comfortable that you fall asleep), and after each session, heated debate would be encouraged. Food and drinks, of course, would be provided. Expert projectionists would screen newly restored films on pristine equipment.

Imagine what could be seen, heard, and learned. Imagine how ideas could be challenged. I am ready to start when you are.

View of “Brendan Fernandes: The Master and Form.” 2018, Graham Foundation, Chicago. Design: Norman Kelley. Dancers: Satoru Iwasaki, Yuha Kamoto, Andrea de León Rivera, Antonio Mannino, Leah Upchurch. Photo: Brendan Meara.

Show: A “queered” collaboration between dancers, artists, and other cultural workers.

Collaboration as a means to create with others has always been a part of my practice. As a dancer, I have always worked in a collaborative context where teams work together and support one another. My dream show would be to invite artists, dancers, musicians, choreographers, cultural workers and scholars to come together in a “queered” space to make something without definition. The show would be a process-based endeavor where the makers would gather throughout the run of the show to make something. What that something is or could be is undefined. I find beauty in shows that are non-traditional, that are in flux, where every aspect of their ephemeral process is the art. We live in times where notions of the imaginary, the making of future possibilities and collective futures are unclear. My dream show would bring people together into a collective to nurture, to be generous, to collaborate in art making, to question art’s form and to arrive at unexpected possibilities. Artists, dancers, musicians, choreographers, cultural workers and scholars who would be part of this show would include: Tricia Brown Dance Company, Will Rawls, David Hammons, Helen Molesworth, Solange Knowles, Ralph Lemon, Rujeko Hockley, Nat Trotman, Juliet Bellow, Taisha Paggett, and Kimberly Drew.

From left: Piero Manzoni’s Base of the World (1961); Jackie Winsor’s Bound Square (1972). Courtesy of MoMA; Paul Thek’s Meat Piece with Warhol Brillo Box (1965); Janine Antoni’s Gnaw (1992); Jim “Isermann: Utopia Now”; Tara Donavan’s Untitled (Toothpicks) (2004).

Show: “The Cube Show, A Brief History of Postwar Sculpture”

Imagine starting at the top of the Guggenheim Museum and walking down the spiral seeing the history of postwar sculpture through the use of a single form, the cube. It would include: Piero Manzoni, Tony Smith, Donald Judd, Richard Serra, Sol Lewitt, Larry Bell, Paul Thek, Andy Warhol, Eva Hesse, Jackie Winsor, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Janine Antoni, Rachel Lachowicz, Rachel Whiteread, Charles Ray, Jim Isermann, Yayoi Kusama, Roni Horn, Rebecca Warren, Cornelia Parker, Tara Donovan, Ai Weiwei, and Urs Fischer, to name just a few.

Bill Viola’s The Quintet of the Astonished (2000). Courtesy of The Broad.

Show: “Ages of Angst and Empathy”

I would love to do an exhibition that considers the art of the late 19th and early 21st centuries through the lens of empathy and compassion. The word empathy was defined and coined within the field of aesthetics in fin-de-siecle Europe, as one era closed and another began. Although empathy is as old as humanity, we didn’t feel the need to define it until the turn of the last century. What happened in society to drive the need for a word that we hadn’t needed for 200,000 years? How can we see the need reflected in the art of the times?

Fin-de-siecle Europe was a time of political, philosophical, and societal angst, marked by urban alienation in a newly industrialized world. Across Europe, there was a widespread fear of losing familiar ways of life and a certain pessimism about the future. At the same time, there was an excitement about the new century and the future opportunities that came with the rapid rate of change that characterized the time.

One hundred years later, we continue to see new opportunities in the future and are experiencing decreased global poverty, technological innovation, and vast advancements in science and in healthcare. Our current moment, as captured by contemporary artists, is also marked by fear and pessimism brought about by declining civility, tyranny, extreme individualism, globalization, immigration and migration, urban alienation, excessive wealth disparities, and climate change—to name just a few contemporary anxieties.

Roger Fry’s Nina Hamnett (1917), in a dress designed by Vanessa Bell and made at the Omega. © University of Leeds Art Collection and Gallery; courtesy of the Public Catalogue Foundation.

Show: Work from the Omega Workshops

One of my dream exhibitions is a large-scale show of work produced by the Omega Workshops, the London-based art and design collective founded by Vanessa Bell, Roger Fry, and Duncan Grant in 1913. Created to challenge what they believed was the false distinction between fine and decorative arts, over the course of six years these artists and their colleagues established a robust market for artist-designed textiles, pottery, carpets, furniture, and other decorative objects.

As we increasingly see the lines between fine art and craft dissolve, and so many artists exploring fashion, textiles, ceramics, and furniture, it would be timely to reevaluate this ground-breaking group of artists who were challenging these conventions a century ago.

Left: Domenico Gnoli’s Striped Trousers (1969). Right: Betty Tompkins’s Pussy Painting #26 (2016). Courtesy of PPOW Gallery, New York.

Show: Domenico Gnoli and Betty Tompkins

When Domenico Gnoli had a show at Luxembourg & Dayan Gallery in 2012, Alissa Bennett, who worked there at the time, said to me that a two-person show of my work with his would be a good combination—and I have thought about it ever since. Luxembourg & Dayan would be a great venue for it; the space lends itself to intense visual discussions.

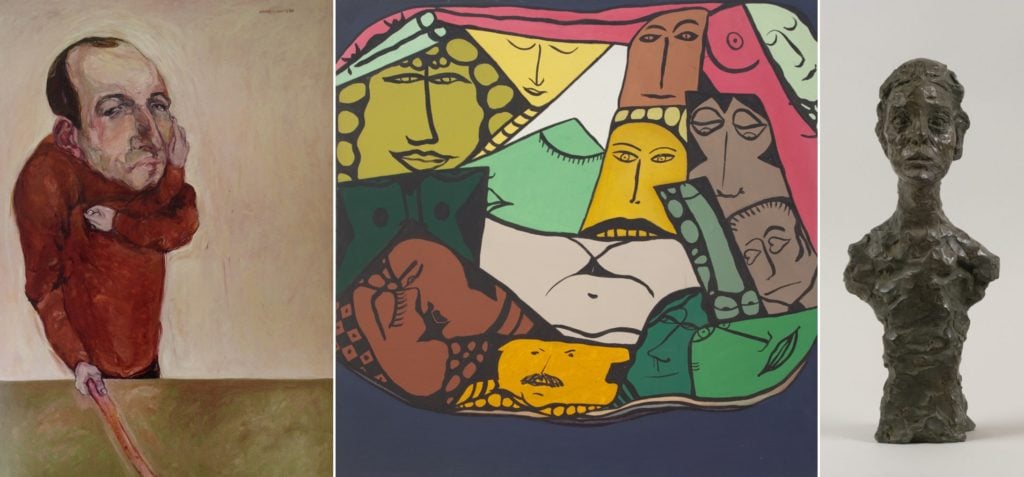

From left: Marwan’s The Husband (1966), courtesy of the Barjeel Foundation; Huguette Caland’s Exit (1970), courtesy of the artist; Alberto Giacometti’s Buste d’Annette X (1965).

Show: Marwan Kassab Bachi, Huguette Caland, and Alberto Giacometti

I would dream of seeing a show between the Syrian-German expressionist Marwan Kassab Bachi, the Lebanese abstract painter and designer Huguette Caland, and Alberto Giacometti. Collectively, these works would speak to the history of the body in all of its forms and contortions: How it can be expanded and abstracted to help us think through how we relate to each other as beings? Perhaps it will be a show that I will have the privilege to put together one day.

Ana Mendieta’s Untitled (Silueta Series) (1978). © Ana Mendieta, courtesy of the Guggenheim Museum.

Show: “New and Recent Works by Eva Hesse” (or Ana Mendieta, Robert Smithson, Gordon Matta-Clark, or Yves Klein)

In thinking about a dream exhibition I went to the truly impossible: artists who died far too young—all in their mid-30s—and yet left behind an extraordinary legacy that continues to exert significant influence over the trajectory of art. What might their careers have produced were they alive today?

Protesters’ signs are left near the White House during the Women’s March on Washington on January 21, 2017 in Washington, DC. Courtesy of Mario Tama/Getty Images.

Show: Protest signs

Inspired by the role of civic institutions at a time when the citizenry of the US is frayed, I yearn for continuous exhibitions in public libraries of placards, signs, and banners culled from contemporary political marches. Not only are these signs an extraordinary exercise in the politics of language, irony, poetry, and design, they also illustrate the ever-important amateur practice of collage. “Stressing the provisional and the handmade aspect,” as art historian George Baker writes of contemporary collage practices, these homespun artifacts represent “an endless if seemingly random proliferation” of the public’s political imagination manifested with markers, paper, cutouts, glue and tape.

Michelangelo’s Pieta.

Photo: Wikipedia.

Show: “Marble superior, Michelangelo’s Pietà”

To create an exhibition around Michelangelo’s Pietà would be a dream come true. This iconic piece from the Vatican defies genre and categories and is extremely curious on every level. Inspired by ancient Greek sculpture, Michelangelo creates a body of white marble that holds both Gothic and renaissance elements, the narrative is abstract yet its carving is done in a “realistic” matter—the faces in particular are extremely realistic, and possibly even self-portraits of the artist. The piece has been replicated several times, by Michelangelo himself and others. I would gather all these in the exhibition, add some Greek sculpture and some marble works by Rodin, who admired and copied Michelangelo in both style and method.

The exhibition would be organized as a reconstruction of Michelangelo’s workshop, including works by some of his pupils, blocks of marble from Carrara, tools, and a floor covered in sketches, clay, marble chippings, old cloth pieces, and wax to polish up the white surfaces. It would raise issues of seriality, original vs. copy, material through time, and Michelangelo’s radical working techniques. Rodin would be key to introduce the legacy of Michelangelo, yet several examples from early modernism—Moore, Bourgeois, Arp—would also be included, as would contemporary artists who use marble. The Pietà would be the centerpiece, with the layout of the exhibition cyclic, as art itself is. The audience would walk both back and forth in time, allowing the eye to wander and connect the works of art across time, artists, and motifs. This work is a life changer, anyone who’s seen it is marked by it and it stays with you.

Left: J.M.W. Turner’s Seascape with a Sailing Boat and a Ship

(c.1825–30), © Tate. Right: Claude Monet’s Rouen Cathedral: The Portal (Sunlight) (1894). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Left: Mark Rothko’s #10 (1952). © Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Photo: Paul Macapia. Right: James Turrell’s James Turrell, Aten Reign (2013). Guggenheim Museum, New York © James Turrell. Photo- David Heald © SRGF.

Show: “Art Light: William Turner, Claude Monet, Mark Rothko, and James Turrell”

Turner painted seascapes with waves, sky, ships, and sun. With time, the light from the sun became as much of a presence as the boats and waves, and all representation disappeared. Influenced by a Turner exhibition in London, Monet applied the same concepts. Later, Rothko painted light as an image of the soul, and Turrell sculpted the light itself.

Clockwise: Desmond Paul Henry, 1964; Ben Laposky’s Oscillon 520 (1960). © The V&A Collection; Manfred Mohr’s P-1273 16627 (2007/8); Jean-Pierre Hébert’s quantic notations (1989).

Show: “On the 8th Day” Can we program computers to make better art than human artists?

This show challenges the assumption that creativity is uniquely biological and human. Works made in partnership with machines, from oscilloscope images of Ben Laposky and the drawing machines of Desmond Paul Henry to other followers of Max Bense’s theories of programmable aesthetics such as Manfred Mohr and Jean-Pierre Hebert, will be paired with the latest in AI and algorithmic research as applied to the fine arts. The show will look at algorithms used by artists throughout time, such as the golden rectangle, to suggest a seamless path to full computerized creations.

Left: Emery Blagdon’s Untitled from “Healing Machines” (ca. 1955–86). Photo courtesy of the John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection. Right: Emma Kunz’s Untitled.

Show: Harald Szeemann’s “Kingdom of Referentials”

In the summer of 1995, Harald Szeemann conceived of an exhibition in four parts titled “The Kingdom of Referentials.” Parts one and two included a selection of works by 32 self-taught American artists, eight large-scale models of American self-taught environments, five monumental European art brut masters of painting, drawing, and sculpture, plus six models of vast European environments.

In part three, Szeemann added work by Vito Acconci, Arnulf Rainer, Marcel Duchamp, Jackson Pollock, Christian Boltanski, and Jean Tinguely; plus groupings of “confrontations” between Henry Darger and Pier Paolo Pasolini; Heinrich Anton Müller and Marcel Duchamp; Clarence Schmidt and Frank Gehry; Emery Blagdon and Emma Kunz; Thornton Dial and Jackson Pollock.

Part four was to be a film program with such obsessive image and movement films as the Heaven and Earth Magic feature by Harry Everett Smith (c. 1957).

In his proposal for this epic project, Szeemann wrote that “parts one through three would be like the fluctuation of breath, so that the exhibition itself would become an artwork—a kingdom of referentials.” In spite of Szeemann’s luminary stature as a curator, the “Kingdom of Referentials” was never realized.

Longhauser will speak about this never-realized show at ICALA on March 14.