People

Artist Françoise Gilot, Who Chronicled Her Turbulent Decade-Long Relationship With Picasso, Is Dead at 101

Picasso never forgave her for publishing a memoir revealing the abuse she suffered in their 10-year relationship.

Picasso never forgave her for publishing a memoir revealing the abuse she suffered in their 10-year relationship.

Sarah Cascone

Artist and memoirist Françoise Gilot, known for her tumultuous relationship with Pablo Picasso, has died at age 101 following heart and lung issues.

Gilot’s daughter, Aurelia Engel, confirmed her death to the New York Times. The centenarian is also survived by her two children with Picasso, Claude Picasso, director of the artist’s estate, the Picasso Administration; and fashion and jewelry designer Paloma Picasso; as well as four grandchildren.

During her life, Gilot was incredibly productive artist, painting well into her 90s and leaving behind some 1,600 canvases and 3,600 works on paper, according to Agence France Presse. She often worked with watercolors to create her vibrant paintings and was a dedicated ceramicist. Gilot received numerous honors in her native France, including the nation’s highest order of merit, the Legion of Honor.

Picasso met Gilot, 40 years his junior, in 1943, approaching her table at a Paris bistro with a bowl of cherries. When she and her friend told him they were artists, he allegedly responded: “That’s the funniest thing I’ve heard all day. Girls who look like that can’t be painters.”

But Gilot, who was born in a Paris suburb into an affluent family, had been an artist since she was three years old. She started out borrowing brushes from her watercolorist mother and, at her father’s insistence, maintained a gruelling schedule of eight hours a day of both painting and legal studies. She had even just had her first show, having dropped out of law school to study art at the Académie Julian.

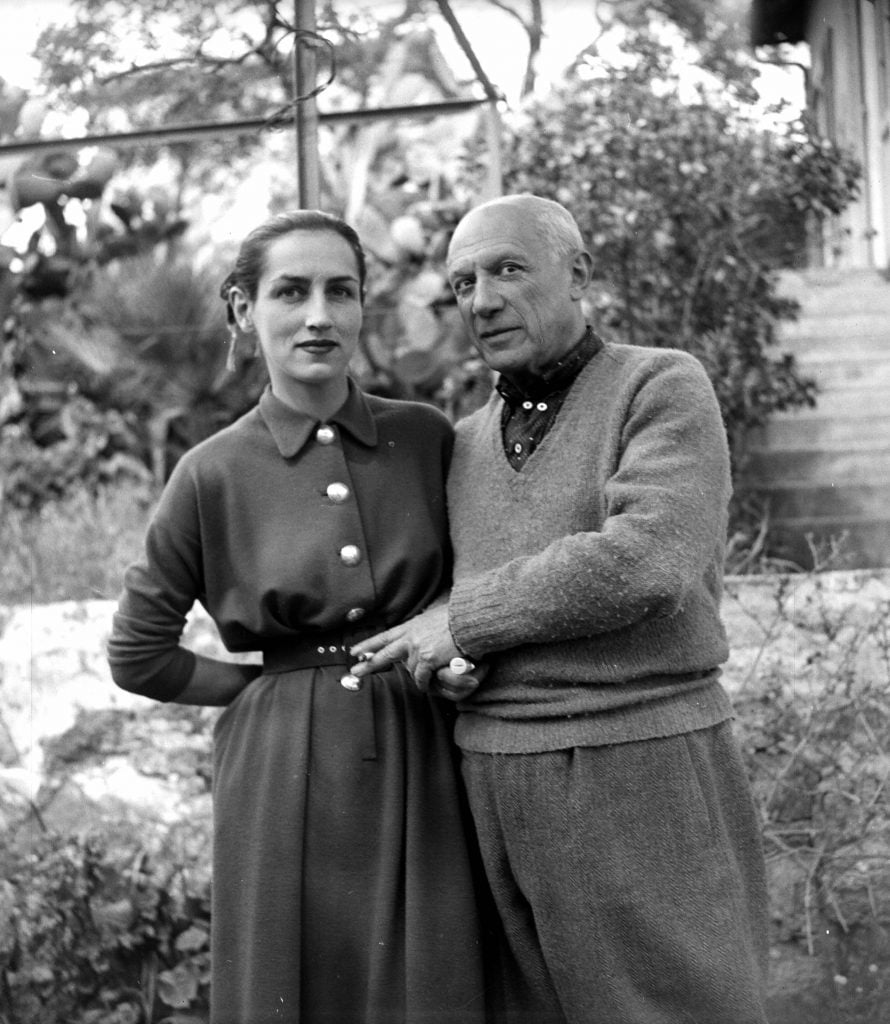

Pablo Picasso and Francoise Gilot in 1952. Photo by Roger Viollet via Getty Images.

Despite being married to dancer Olga Khokhlova, Picasso was immediately entranced by the 21-year-old artist, whose early work had a distinct Cubist bent. Gilot became a key muse for the older artist, who depicted her in masterpieces such as Woman-Flower (1946) and Femme assise (1949), which sold at auction for £8.5 million ($9.6 million) in London in 2012.

In the end, Gilot was the only woman to leave Picasso on her own terms. (The two were together for a decade, but never married.)

“Pablo was the greatest love of my life, but you had to take steps to protect yourself. I did, I left before I was destroyed,” Gilot recalled in Artists and Conversation, a 2021 book by Janet Hawley. “[Picasso was] astonishingly creative, a magician, so intelligent and seductive… But he was also very cruel, sadistic, and merciless to others, as well as to himself.”

Francoise Gilot and her daughter Paloma Picasso in 1952. Photo by Roger Viollet via Getty Images.

When she left him, Picasso told her “you imagine people will be interested in you,” according to a 1979 article in People. “They won’t ever, really, just for yourself. It will only be a kind of curiosity they will have about a person whose life has touched mine so intimately.”

Picasso has been back in the headlines recently as exhibitions around the world mark the 50th year since his death. The renewed attention has also brought up his well-documented mistreatment of women. This dark legacy is the subject of a critically panned exhibition, “It’s Pablo-matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby,” at the Brooklyn Museum.

In a followup to her 2018 standup special that skewered Picasso’s problematic personal life, comedian Gadsby pairs the late Spanish artist with women artists such as Renee Cox, Käthe Kollwitz, Dindga McCannon, Ana Mendieta, and Marilyn Minter. Gilot and Picasso’s other lovers and muses, such as the artist Dora Maar, are mentioned in the exhibition, but their work is notably absent.

Francoise Gilot in 2015. Photo by Andrew Toth/Getty Images.

For her own part, Gilot was outspoken about her time with the famous artist, infamously publishing a best-selling memoir about their relationship, Life With Picasso, in 1964. (It was later adapted into the 1996 film Surviving Picasso, with Anthony Hopkins as the title role and Natascha McElhone playing Gilot.)

The book detailed Picasso’s physical and emotional abuse. “He took the cigarette he was smoking and touched it to my right cheek and held it there,” Gilot wrote. “He must have expected me to pull away, but I was determined not to give him the satisfaction.”

Picasso filed three unsuccessful lawsuits against the book, and never forgave Gilot for writing the revealing account of their life together. He attempted to sabotage her art career, and would remain estranged from their children for the rest of his life.

Gilot and Jonas Salk after their wedding in Neuilly-sur-Seine near Paris, France. Photo by Michel Ginfray/Sygma/Sygma via Getty Images.

Gilot went on to marry twice, having her third child, Engel, with Luc Simon, a childhood friend. (The marriage lasted from 1955 to 1962.) In 1980, she married scientist Jonas Salk, inventor of the polio vaccine. They remained together until his death in 1995, but spent half of each year apart to focus on their respective careers, with Gilot keeping studios in New York and Paris.

She also served as chairwoman of the fine arts department at the University of Southern California, 1976 to 1983.

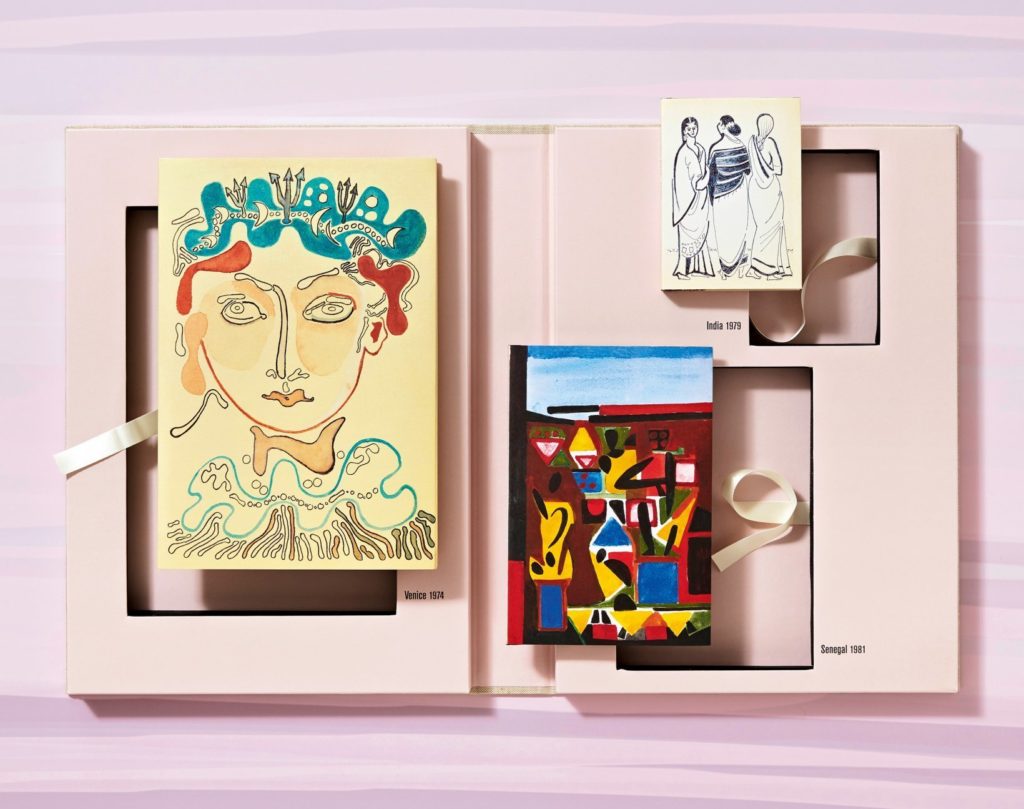

Françoise Gilot. Three Travel Sketchbooks: Venice, India, Senegal. Photo courtesy of Taschen.

Her work can be found in the collection of institutions including the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris; the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Museum of Modern Art in New York; and the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C.

In recent years, Gilot’s profile as an artist had risen. Gagosian organized “Picasso and Françoise Gilot: Paris–Vallauris 1943–1953,” the first exhibition pairing her art alongside that of Picasso, in 2012. In 2018, she published a facsimile edition of a trio of sketchbooks she made from 1974 to 1981, while traveling to India, Senegal, and Venice. Last year, the New York Times declared her an “‘It Girl’ at 100.”

Francoise Gilot, Paloma à la Guitare set an auction record for the artist with a £922,500 ($1.3 million) sale at Sotheby’s London in 2021. Photo by John Phillips/Getty Images for Sotheby’s.

Gilot’s auction record stands at £922,500 ($1.3 million), set at Sotheby’s London in 2021 for her oil painting Paloma à la Guitare, according to the Artnet Price Database. It was her first work to hit seven figures, and she had to wait for that milestone until the year she turned 100.

Picasso, on the other hand, for a time commanded the highest price ever achieved at auction with the 2015 sale of Les femmes d’Alger (Version ‘O’) for $179.4 million—since eclipsed only by Leonardo da Vinci’s $450 million Salvator Mundi.

More Trending Stories:

The Art Angle Podcast: James Murdoch on His Vision for Art Basel and the Future of Culture

A Sculpture Depicting King Tut as a Black Man Is Sparking International Outrage