People

Frank Auerbach, Master of Psychological Realism, Dies at Age 93

Considered one of the greatest painters of his age, he was a leading figure among the School of London artists.

Considered one of the greatest painters of his age, he was a leading figure among the School of London artists.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

The highly influential British artist Frank Auerbach, whose vigorously impastoed, semi-figurative paintings made him a leading figure among the School of London painters, has died, aged 93.

Though he was notoriously reclusive, Auerbach is best known for his association with a wider group of London-based figurative painters who all gained international renown, including David Hockney, Francis Bacon, and Lucian Freud, with whom he was particularly close.

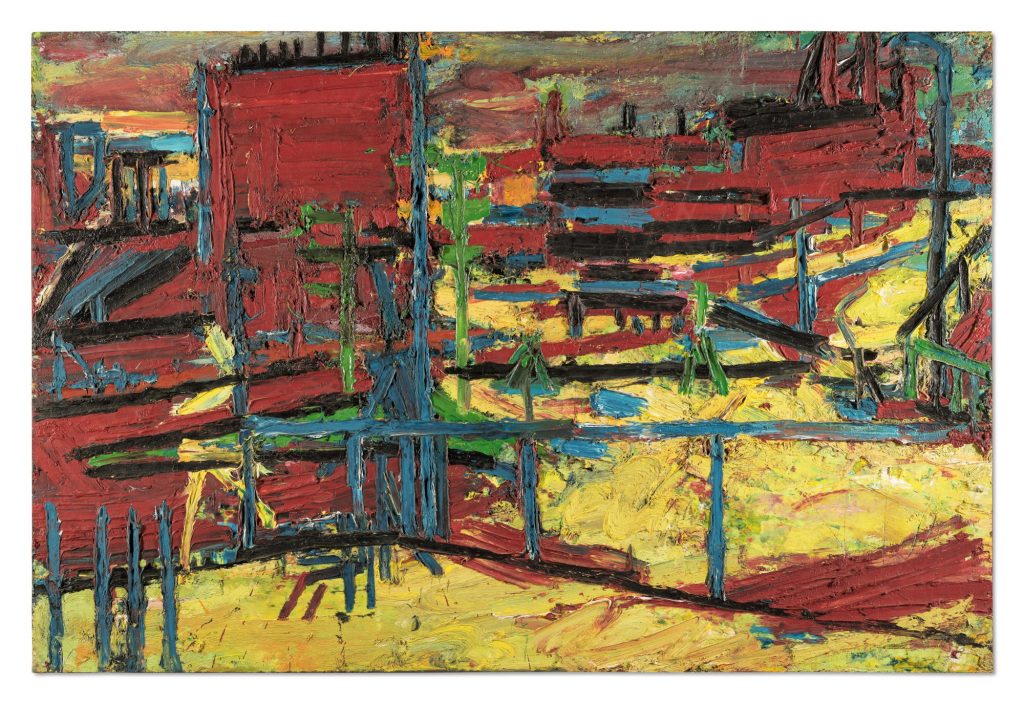

In his paintings, there were a few subjects that Auerbach returned to repeatedly, including the London borough of Camden where he lived and his “heads,” portraits of a small circle of preferred sitters, including friend Estella Olive West, professional model Julia Yardley Mills, and his wife Julia. Dispensing with straightforward naturalism in favor of a more profound psychological realism, Auerbach’s distinctive style emerged from working ever more dense layers of paint on canvas until his works took on an embodied liveliness.

“As soon as I become consciously aware of what the paint is doing my involvement with the painting is weakened,” he once said. “Paint is at its most eloquent when it is a by-product of some corporeal, spatial, developing imaginative concept, a creative identification with the subject.”

Frank Auerbach’s Mornington Crescent(1969) sold for $7 million at Sotheby’s in 2023. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Auerbach was born in Berlin on April 29, 1931 to Jewish parents; his father was a lawyer and his mother an artist. In 1939, at the age of just seven, Auerbach fled Germany to the U.K. via a private arrangement similar to the Kindertransport scheme, leaving behind his parents who were both murdered at Auschwitz in 1942. He became a naturalized British citizen in 1947.

Educated at a British boarding school for orphans, Auerbach showed an early interested in art and, after briefly pursuing acting, enrolled at St Martin’s School of Art and later the Royal College of Art, from which he graduated in 1955. He once joked that his earliest motivation to become an artist “was a horror of having to work in a bank or an office, a desire for a free and creative life.”

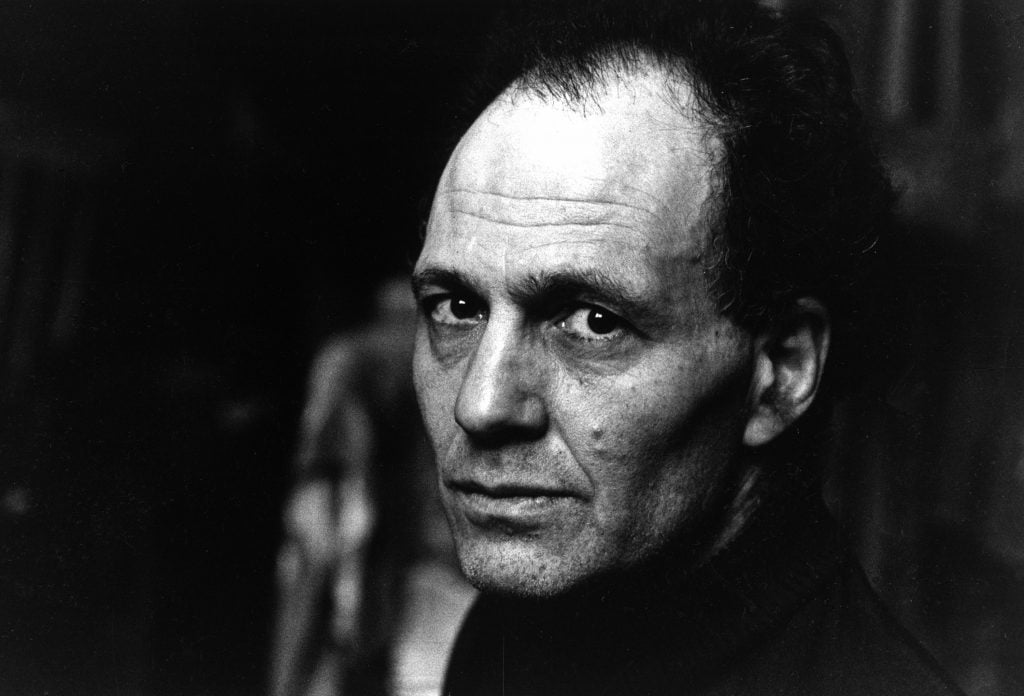

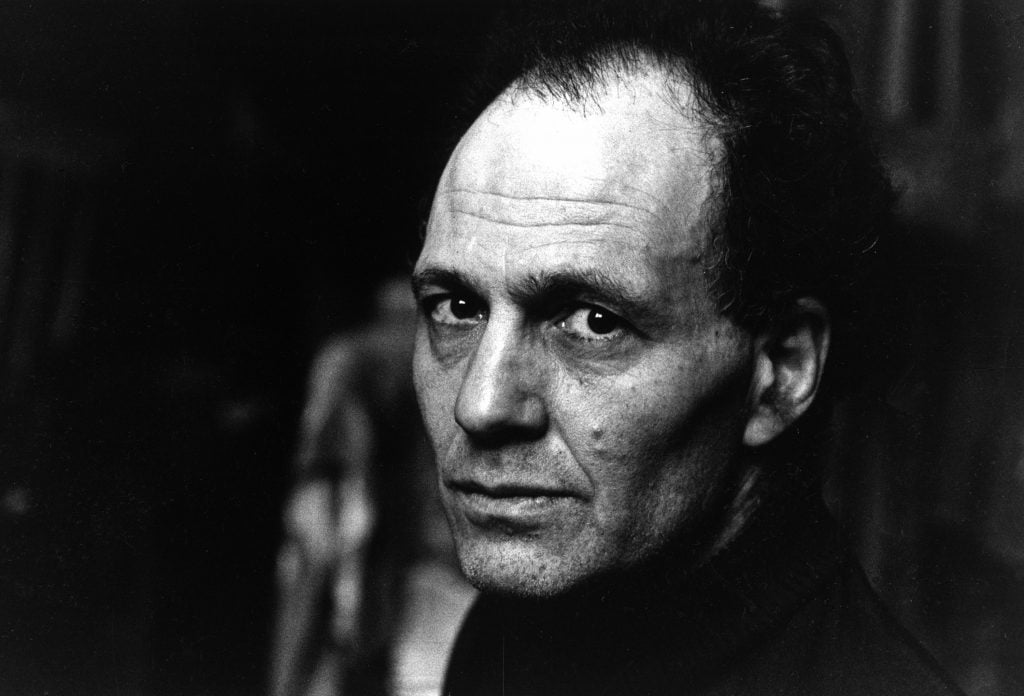

Frank Auerbach in his studio in Camden, London, 1962. Photo: Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

By the early 1960s, he was teaching at Camberwell School of Art, where he was known to be a generous mentor to the younger painters in which he saw promise.

At the same time, Auerbach was establishing himself on the midcentury London art scene, an enclave for enthusiasts of figuration at a time when global attention was instead on New York and Abstract Expressionism. From 1956, Auerbach had regular solo shows at Beaux Arts Gallery, a decade later moving to Marlborough Fine Art, which gave him his first New York show in 1969.

Frank Auerbach, Head of Gerda Boehm (1965). Courtesy of Sotheby’s London.

Describing his process, Auerbach said he would start his days by drawing and later switch between painting and drawing when tackling large-scale landscapes. For smaller “heads,” he would work directly onto the canvas, repeatedly scraping away and reapplying paint until he had achieved the effect he was after.

“Each picture has its own history,” he once said. “The only constants are the fact that it always takes a long time, sometimes a very long time…”

Since receiving his first solo museum show at the Hayward Gallery in 1978, Auerbach has been the subject of international institutional showings too numerous to list. Highlights include winning the Golden Lion (alongside Sigmar Polke) for his Great Britain pavilion at the 42nd Venice Biennale in 1986, and major retrospectives at the Reina Sofia in Madrid (1987), National Gallery in London (1994), Tate Britain in London and Kunstmuseum Bonn (2015).

Installation view of Frank Auerbach’s “The Charcoal Heads” at the Courtauld Gallery. Photo: Fergus Carmichael

Earlier this year, his wonderfully sensitive but haunting portrait sketches were the subject of “Frank Auerbach: The Charcoal Heads” at the Courtauld Gallery in London.

In his final years, Auerbach turned his eye onto himself, producing a remarkable series of self-portraits. Speaking to the Guardian last year, however, he reflected on many decades spent portraying those close to him. “It’s possibly true that our deepest experiences are other people,” he said, adding “and it seems that the only thing worth using for one’s art is one’s deepest experiences.”

Frank Auerbach. Photo: David Dawson

Auerbach had always worked very long hours, seven days a week, and this obsessive nature only intensified with age. “Sometimes I keep on drawing in my sleep,” he said last year. “Before, I was hardly conscious of my dreams, but I now find myself working things out, thinking I should be doing this with that.”

“We have lost a dear friend and remarkable artist but take comfort knowing his voice will resonate for generations to come,” said Frankie Rossi Arts Projects’s director Geoffrey Parton. Auerbach is survived by his son, the filmmaker Jacob.