People

‘You Feel Powerless’: Hong Kong Artist Wong Ping on Unveiling His First UK Museum Show While His Family Protests Back Home

We spoke to the artist about marching in the streets and why he is not afraid of being blacklisted in mainland China.

We spoke to the artist about marching in the streets and why he is not afraid of being blacklisted in mainland China.

Naomi Rea

When I arrive to interview the artist Wong Ping at the Camden Arts Centre in London, he is anxious. Back home in Hong Kong, protesters have just stormed a government building after weeks of escalating action against a controversial new extradition bill. He has been tensely refreshing his news feeds all day, upset by the police’s increasingly violent response to protesters.

“It’s sad to look at that from far away,” Wong says. “You feel powerless.” While the artist is in London unveiling his first solo museum exhibition in the UK, the latest protests are taking place on the anniversary of the former British colony’s handover to China. Like many young Hong Kongers, Wong was, until a few days ago, out there demonstrating in the street alongside his peers. His parents are still marching as we speak. Fearful for their safety, he tells me that he has just texted them to go home.

For the Camden show, he is showing films set inside new installations across two spaces in London. Titled Fables 1 and Fables 2, they are Wong’s updated version of moral folk tales. His 2018 film, Dear, Can I give you a hand?, commissioned by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Chinese Art Initiative, is playing in an installation surrounded by chattering golden dentures in Camden’s white-cube space. He is presenting new films in a more industrial pop-up space on Cork Street in Mayfair.

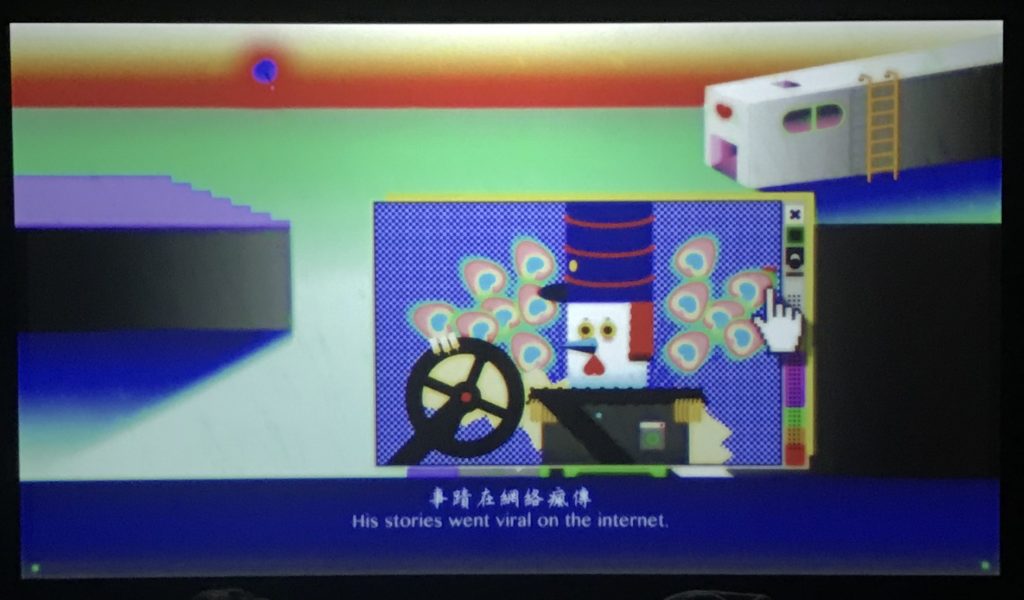

Wong Ping, still from Wong Ping’s (2018).

Wong’s colorful animations, populated with animal characters, including a capitalist cow and a three-headed homicidal rabbit, hold up a twisted mirror to contemporary society. One tale was inspired by an incident he witnessed while on a bus. He saw a cockroach—one of his biggest phobias—crawling up the arm of a pregnant woman. It sent his mind spinning. Should he tell the woman? What if he startled her into miscarrying? What if her screams caused the bus driver to crash? In the end, he just kept silent.

“This pathetic story can be related to anything in life, and even the situation of Hong Kong nowadays,” Wong explains. “We think a lot: should we go harder? Should we take over the counsel, the office of the government? Maybe I should just be a good protester, a quiet protester. And in the end nothing happens, and we are still controlled by China.”

Wong’s London show is the result of his winning the Camden Art Centre and Frieze Art Fair’s new prize for emerging artists. The artist’s technicolor and darkly humorous animations, which are narrated in deadpan Cantonese, impressed the judges on the booth of Edouard Malingue Gallery in the Focus section of Frieze London last fall.

Winning the inaugural prize is just one of an impressive collection of accolades the self-taught artist has collected lately. He was included in the 2018 New Museum Triennial and the Guggenheim’s show “One Hand Clapping.” This year, he has had solo exhibitions at the Kunsthalle Basel and the Dusseldorf non-profit CAPRI. In May, he won another prize, this time at Rotterdam’s International Film Festival.

Wong, who got his BA in multimedia design from Curtin University in Perth, Australia, in 2005, was working in post-production on cheesy dramas at a TV station in Hong Kong when he made his first art animations. Bored of his day job spent digitally removing wires and airbrushing actors’ skin, he found art was an escape. “It was so depressing, so I went back home and created my little animations, and posted them online,” he says. After gaining a following, he was soon discovered by players in the Hong Kong art scene.

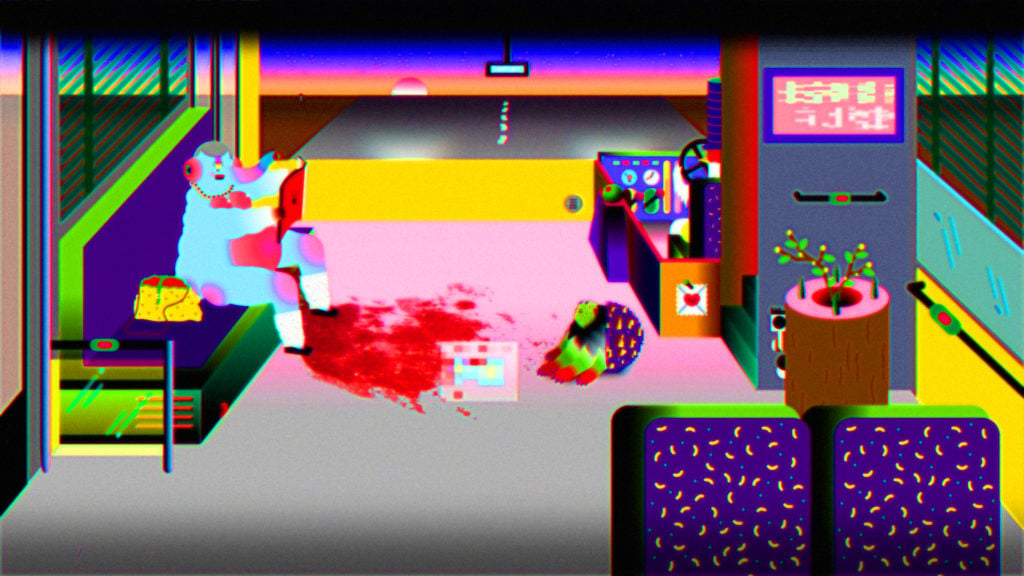

His surreal digital animations are based on elaborate stories he writes, which often draw from his own life. The darkly absurd technicolor animations recall the design aesthetic of 1980s video games, and his style has also been likened to the Modernism of Fernand Léger, the pop art of Tom Wesselmann and Allen Jones, and design environments of the Memphis Group. He founded the Wong Ping Animation Lab in 2014, is represented by Edouard Malingue Gallery in Hong Kong and Shanghai, and has recently secured gallery representation in New York and Los Angeles with Tanya Bonakdar Gallery.

Wong Ping, still from Wong Ping’s Fables 2 (2019). Image courtesy of Edouard Malingue Gallery and the artist.

We touch on his fears for the protesters in Hong Kong. Wong explains that the actions of the past month have been brewing ever since China’s “one country, two systems” principle was formulated in the 1980s. He says it is a natural consequence of the lack of government response to the 2014 student-led Umbrella Movement, which also protested against the incursion of mainland Chinese influence. Wong supports the goals of the current protests: for the extradition bill to be fully withdrawn, not just suspended. “We don’t want it being mishandled by the Chinese government,” he says. He also supports calls for the territory’s Beijing-approved leader, Carrie Lam, to resign.

The exiled Chinese artist Ai Weiwei has also spoken out in support of the demonstrators, and members of his studio have been documenting events as they unfold, posting footage and images on social media. It has gotten Wong thinking what his role as an artist should be in all this.

“Someone like Ai Weiwei has such a huge reputation, power, and followers, so I think something will actually come from what he says,” Wong says. “For me, [a] tiny, little artist, I really don’t know. Direct action, I think, more than animations.”

Wong Ping, still from Wong Ping’s Fables 1 (2018). Image courtesy of Edouard Malingue Gallery and the artist.

Is he afraid of the consequences of speaking out? “No,” he says. “In Hong Kong, we still have the freedom to speak.” He says there is more of a problem of self-censorship, as most prominent figures in Hong Kong don’t want to be blacklisted in China.

For his part, Wong is not afraid of ending up on a blacklist. After all, he says, collectors can still buy his work in New York. He has only exhibited a couple of times on the mainland, and then only his more “mild” works have been approved by the government’s censorship bureau. It is only when spaces have bypassed the censorship process, at risk of being shut down, that he has been able to show the full breadth of his work in China.

As the political situation worsens, has he considered leaving Hong Kong? Wong says he doesn’t want to move because his family and work is based there. But he has witnessed a brain drain from the city in recent years. An increasing number of his talented friends have migrated to Taiwan, Berlin, or the United States.

“It’s been a long and depressing period for Hong Kong, you can see nothing is moving forward,” he says. For now, he’s staying put, but he’s watching events closely.

Wong Ping, still from Who’s the Daddy (2017). Image courtesy of Edouard Malingue Gallery and the artist.

“Wong Ping: Heart Digger” is on view through September 15 at the Camden Arts Centre in London.