On View

How Big a Deal Is Michael Heizer’s ‘City’ When It Comes to Art History? We Asked Curators, Collectors, Dealers, and Scholars to Weigh In

“People are just dying to see it. And it's going to wow them," said one observer.

“People are just dying to see it. And it's going to wow them," said one observer.

Taylor Dafoe

It’s not hyperbole to say that Michael Heizer’s City is a work of art unlike any other.

Five decades in the making, the Land Art pioneer’s magnum opus stretches out like an abandoned alien complex in the desolate Nevada desert, a crop circle without the crops—which some Google Earth users are sure to mistake it for, given that Area-51 is just one valley over.

Groomed gravel paths give way to towering concrete shapes and massive mounds of earth. So primal and powerful are Heizer’s forms that they recall ancient structures—temples, pyramids, henges—more than they do modern industrial ones. The whole thing runs a mile and a half long and half a mile wide, making it among the largest artworks in the world—though few actually know where it is. Even fewer have seen it in person.

“There’s no one else in the modern era that has taken on a project of this magnitude and then stuck with it,” said Emily Wei Rales, director of the Glenstone museum and a longtime supporter of Heizer.

Rales recently joined the board of the Triple Aught Foundation, a nonprofit formed 25 years ago to oversee City. “I would say the length of time and the amount of labor and resources that he’s poured into this—it’s on a scale of something people would do in medieval times.”

With City’s singularity comes a challenge: How do we begin to understand the achievement of this artwork? The years of anticipation, the artist’s unconstrained ambition, and the scale of its footprint make it big in every sense of the word—but is it also a big deal? In terms of art history, how will it be remembered?

Michael Heizer, City (1970 –2022). © Michael Heizer. Courtesy of the Triple Aught Foundation. Photo: Eric Piasecki.

For the first time, we have a chance to answer that question. After 52 years of work, City is finally open to the public.

And yet, in typical Heizer fashion, it remains almost as difficult to see. Just one group of six people is allowed to see the artwork per day. Reservations are required, and mostly spoken for (viewings are booked through the rest of this year).

Those who have scored a viewing will be directed first to the tiny town of Alamo, Nevada—about 90 miles north of Las Vegas—and to the office of the Triple Aught Foundation. From there, a staff member will drive guests three hours—the last of which takes place entirely on bumpy dirt roads—to Heizer’s masterpiece.

Those who have seen City don’t seem to regret the arduousness of the journey to get there. “There is no other sculpture, no other architecture, no other kind of art experience I’ve had that is like it,” said Kara Vander Weg, a director at Gagosian and a Triple Aught board member since 2018.

Vander Weg knows City better than almost anyone, having spent five months at Heizer’s nearby ranch during the pandemic. She’s walked along the artwork, run around it, driven through it. “You don’t see the City project until you’re in the City project,” she said. “That’s one of the genius ways in which Michael has designed it.”

Comparisons have been made to other Land Art masterpieces, Vander Weg pointed out—works of art that, because of their size and destination status, have garnered a kind of metonymic relationship to their creators: Walter De Maria’s The Lightning Field (1977), Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970), Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels (1973-76), James Turrell’s Roden Crater.

“Each of [those] is a great artwork in and of its own, but this is different,” she said.

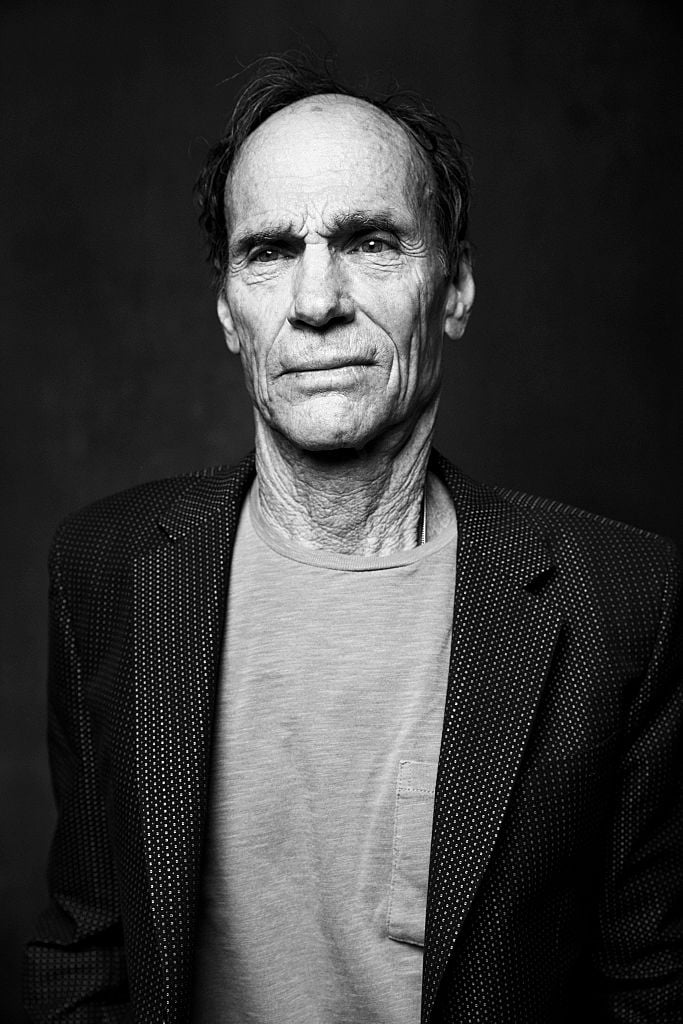

Michael Heizer, 2015. Photo: Jesse Dittmar for The Washington Post via Getty Images.

Heizer began City way back in 1970, and has been chipping away at it—often literally—ever since. A mythology grew around the project and its creator, this dogmatic cowboy who, decades ago, decamped to the remote Great Basin to devote himself to his life’s work. Though he continued to make other forms of art, his presence in the art world all but evaporated, save for the occasional interview, for which he would offer anachronistic—and sometimes slightly offensive—statements that made him sound like a man who never left the 20th century.

“A decaffeinated, used-up, once-was quick-draw cowboy, a sissy boy who eats at Balthazar for lunch,” is how Heizer described himself in a 2016 New Yorker profile, lamenting the loss of his younger self’s id. “Chemical castration—doesn’t happen all at once,” he said. “It’s slow. You just wake up one day and you’re dickless.”

In a way, Heizer is living in another time. “Imagine somebody who is essentially working without any deep relationship to peers,” said Julian Myers-Szupinska a Land Art scholar who has written about Heizer on several occasions. “If he’s bouncing off of anything, it’s weird bunkers and architectural forms of that region, or it’s the archeological record of massive indigenous community-constructed architectures.”

“Where you fit that into the contemporary I don’t know,” Myers-Szupinska continued. “I don’t think it does fit into the contemporary. And I don’t think he aims for it to. The scale on which this project is aimed is the long term. He wants it to be there in 500 years.”

“My good friend Richard Serra is building out of military-grade steel,” Heizer said in that same New Yorker piece. “That stuff will all get melted down. Why do I think that? Incans, Olmecs, Aztecs—their finest works of art were all pillaged, razed, broken apart, and their gold was melted down.”

“When they come out here to fuck my City sculpture up, they’ll realize it takes more energy to wreck it than it’s worth.”

Michael Heizer, City (1970 –2022). © Michael Heizer. Courtesy of the Triple Aught Foundation. Photo: Eric Piasecki.

In 2022, erecting an artwork with the intention of it lasting hundreds of years feels almost comically ambitious. When Heizer began City, on the other hand, a sense of wonder and mythos remained in the American West—a vestigial glimmer of “manifest destiny.” Today, the once-sprawling landscape lives under permanent threat—of fracking, strip mining, or other forms of fossil fuel extraction; of corporate development or environmental calamity. What once felt abundant now feels precarious.

City itself has been embroiled in a political fight for years. A railroad for transporting nuclear waste to Yucca Mountain once threatened to disrupt the land surrounding Heizer’s artwork before longtime Nevada Senator Harry Reid urged then President Obama to declare the region a National Monument in 2015. (Two years later, President Trump considered undoing Obama’s executive order, which would have re-opened the land for development.)

Similarly, the size of City is sure to induce eye rolls from those who interpret Heizer’s project as an ego-driven exercise in artistic man-spreading. Couple that with the fact that City cost $40 million to build and it’s tempting to wonder whether it merited such vast resources.

But Myers-Szupinska warns against that line of thinking. The scholar points to the “sprawl of Las Vegas and the effort of the Hoover Dam and Lake Mead, the militarization of the [land], and all that generates the modernized American West. The scale of the earthwork that is Nevada is mind-boggling.”

“The relative scale of what Heizer’s doing, it’s just puny by comparison,” Myers-Szupinska went on. “There are all kinds of massive things that get constructed that cost more than this. So why is an aesthetic purpose any less valid?”

“Measurements are one way our culture tries to talk about artworks—the time, the size, the remoteness, the distance from a place,” added Vander Weg. “Those are measurements, but they are not the summary of this artwork.”

“Complex One,” City. © Michael Heizer/ Triple Aught Foundation. Courtesy of the artist and Triple Aught Foundation. Photo: Mary Converse.

William L. Fox, the founding director of the Center for Art and Environment at the Nevada Museum of Art, compared the experience of City to a kind of meditation. “When you are down inside it, it’s not that you can’t see the mountains. It’s just the mountains mentally disappear,” he said. “Everything arises around you and you’re powerfully enfolded.”

Fox wrote about Heizer in two books published in the early 2000s: Mapping the Empty, about artists and Nevada, and The Void, The Grid, and The Sign, about the Great Basin. Fox was close with Heizer then, spending time at his ranch and seeing City take shape. But the two men fell out shortly thereafter, partly because the artist despised what Fox had written about his creations.

In 2019, Fox published a career-spanning—and occasionally critical—book about Heizer, who he has called a “highly problematic character.”

But when asked about his thoughts on City, Fox had no trouble putting his complicated relationship with the artist aside. “When Heizer’s at his very best, you experience reverence and awe,” Fox said. “That’s what he wants you to experience inside [City] and you do.”

“People are just dying to see it. And it’s going to wow them,” he said. “It’s not compromised in any way.”