This is the first interview in a four-part series by Folasade Ologundudu featuring Black artists across generations who work with social practice.

The exhibition “Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces” will debut at the Museum of Modern Art in New York almost half a century after Linda Goode Bryant first opened the doors of the gallery that inspired the show just a few blocks away, on West 57th Street.

At that time, JAM was the only gallery of its kind. Black-owned and operated, it existed to champion Black artists in the center of New York City’s incomparable art scene in the 1970s and ‘80s. Although many of these names—David Hammons, Senga Nengudi, Howardena Pindell—are now considered among the most important figures in 20th century art, they had vanishingly few spaces to show back then.

A mother of two, artist, activist, and filmmaker, Bryant has always operated outside the mainstream. She is a tenacious self-starter, devoted mother, generous friend, and fierce advocate who has spent her life and career working to share the stories and positively impact the lives of those who have experienced racism, poverty, and displacement.

Bryant’s best-known works include JAM (Just Above Midtown) gallery, which ran from 1974 to 1986; the 2003 documentary film Flag Wars, which traced the tension between the white gay community and the Black community in Bryant’s hometown of Columbus, Ohio; and Project Eats, an urban farming initiative that occupies vacant lots and rooftops across New York City, which she still runs.

Over the past decade, several institutions have asked Bryant to stage an exhibition about JAM, but she always replied that she didn’t do “dead art shows.” She resisted the notion of a historical show that placed living artists who’ve continued to create new work in conversation with a project that existed decades before. But the significance of doing a show at MoMA—which, although nearby, might as well have been miles away from JAM when it was operating—proved compelling.

Is the acclaim being bestowed upon Black artists today too little, too late? One would be remiss not to mention that recent museum solo shows for artists such as 79-year-old Pindell and 87-year-old Lorraine O’Grady, who showed at JAM decades ago, feel backhanded after all these years. Bryant knows full well that Black creativity and talent exist outside white institutions and have never needed their permission or validity.

On a warm summer afternoon, I sat down with Bryant to talk about her reasons for finally agreeing to a museum show, her hopes for the future, and why she believes a sense of community is lacking among young Black artists today.

Linda Goode Bryant in situ at JAM in 1978. Photo courtesy of Linda Goode Bryant.

Your forthcoming show at MoMA opens on October 9. It feels like a full-circle moment. Your gallery JAM was located just blocks from the museum in the late 1970s and ‘80s, a time when Black artists were systematically denied full visibility to exhibit their works in white-run institutions. Tell me a little bit about this show.

I want to start by saying that before agreeing to do this show, there had been requests from other museums over the past 10 to 15 years. I closed JAM [the gallery] in 1986 and then closed the organization in 1988. In that two-year period, we were doing things publicly, but closing JAM was what I call a self-exile from the art world. I was of the opinion that what was going on in the market was undermining creativity and I wasn’t interested…. I started doing films.

The opportunity came up within the past five years to do a show at MoMA. Initially, I was reticent but I kept thinking about those years on 57th Street where we were literally four blocks away and how difficult it was to be on 57th Street because the majority of the galleries were really hostile to the idea that JAM even existed at all. On top of that, there was a museum just a few blocks away that also was not receptive. There was no way to cultivate the interest of folks from the museum.

When I had an opportunity to consider [the exhibition], initially I said, “I don’t do dead art shows.” What I meant by that is there were so many artists who showed at JAM who are still alive today and the idea of putting them in only a historic space that didn’t consider that they continue to produce is something I wasn’t interested in. But when this came up with MoMA, the relationship between JAM and MoMA really struck me as institutions that in their own ways were more designed to support art and the public’s engagement of art. I said to myself, “Wow, I wonder if it’s possible for JAM to be JAM at MoMA?”

Artists in the show include David Hammons, Howardena Pindell, and Lorraine O’Grady. Some of their work is only just now being highlighted in prominent institutions more than 30 years later. What are your thoughts on artists of your generation who are finally receiving critical acclaim from institutions that have historically denied them access?

Let me just say, JAM was a challenge. It was expressed a lot by Black, Latinx, Native American and Indigenous artists, that they won’t let us show in their institutions, they won’t let us show our work side by side with our white counterparts. At the time I was working at the Studio Museum in Harlem as the director of education and I was responsible for the artist residency program. A lot of those conversations happened in the residency and I found myself saying, “Fuck them, let’s do it ourselves.” The purpose and the intent of JAM was not to be part of a market that wasn’t interested in what we were doing. It was about, how do we create a market for our work? So a lot of the things we did involved cultivating Black collectors who had never purchased or had only purchased a few figurative works, because that was also a tension at the time JAM opened in ‘74. There has been a debate between Black artists since the middle to late ‘60s, as I recall it, about whether you were a Black artist if your work was abstract or conceptual.

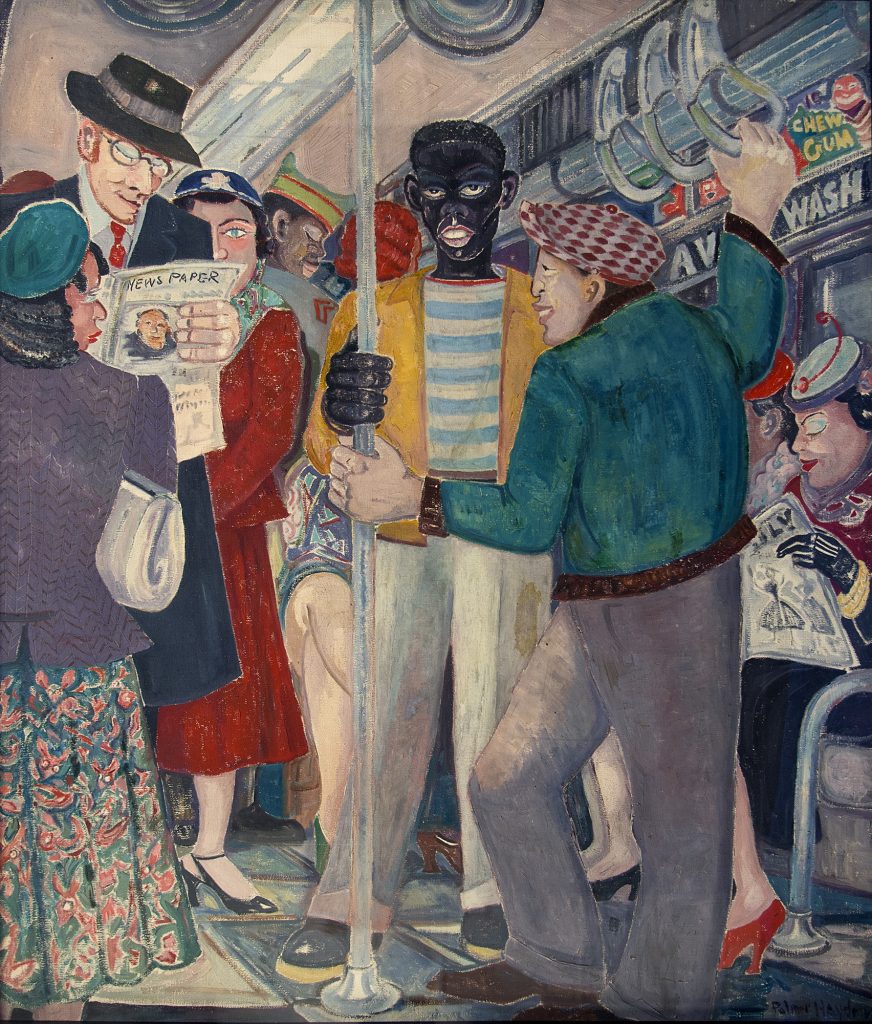

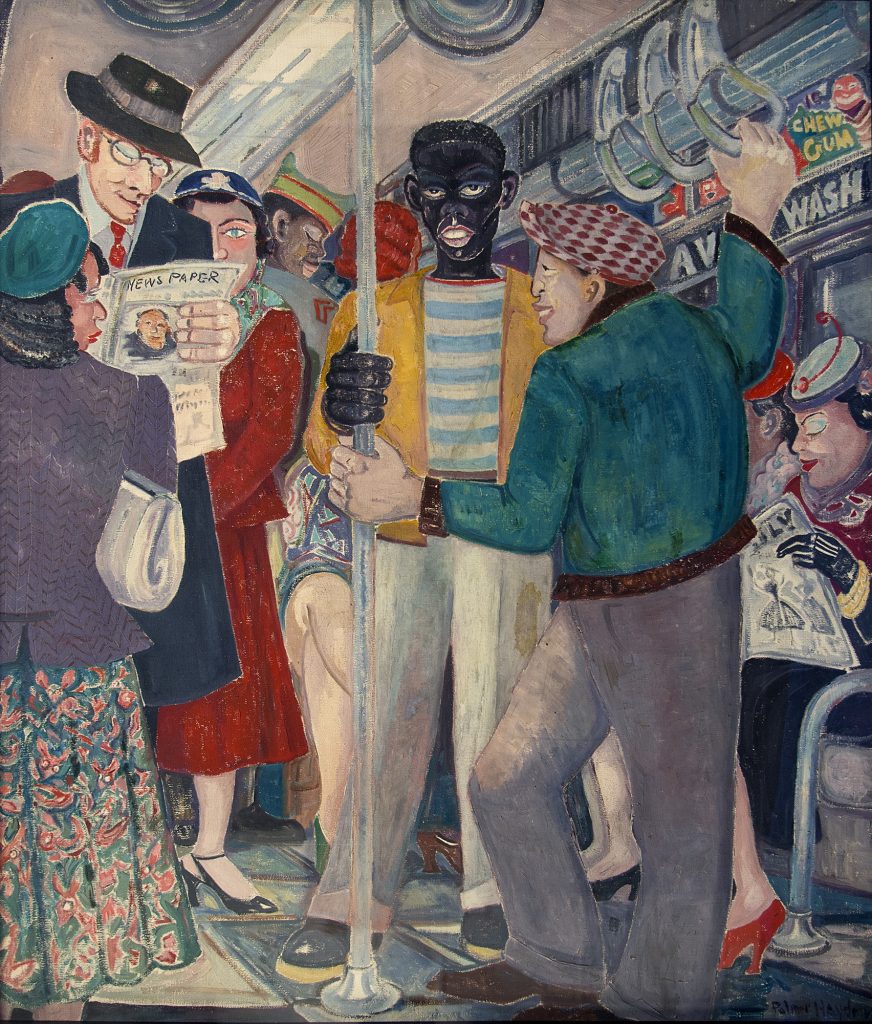

Palmer Hayden, The Subway (c. 1941). The Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller Empire State Plaza Art Collection

The Black Arts Movement paved the way for so many emerging Black artists working today. What was so special about that time and why is it still so relevant today?

The situation was different. You weren’t hemmed in by, “If I do this, it’s likely I’m going to screw myself in terms of being able to have my work seen,” because they weren’t showing our work. Many of us were part of the Black Power Movement as activists as well as artists and we had nothing to lose. To be clear, JAM operated on debt—on my credit card debt—and I was a single mom with two kids. We were driven by a passion to make things and driven by our need for people to engage that work so that we learn from it.

Today, I think the opportunities provided that motivate artists to go into the gallery system, to the dominant infrastructure, are very different. I find it disturbing, quite frankly, that increasingly the artists who are being shown in major galleries are figurative artists painting, drawing, and producing Black figures. Only this time it’s being determined by galleries—white galleries. It’s not uncommon that I’ve heard artists say, “I’d rather be working abstractly right now but I’m making figurative work because that’s what they want.” That hurts me.

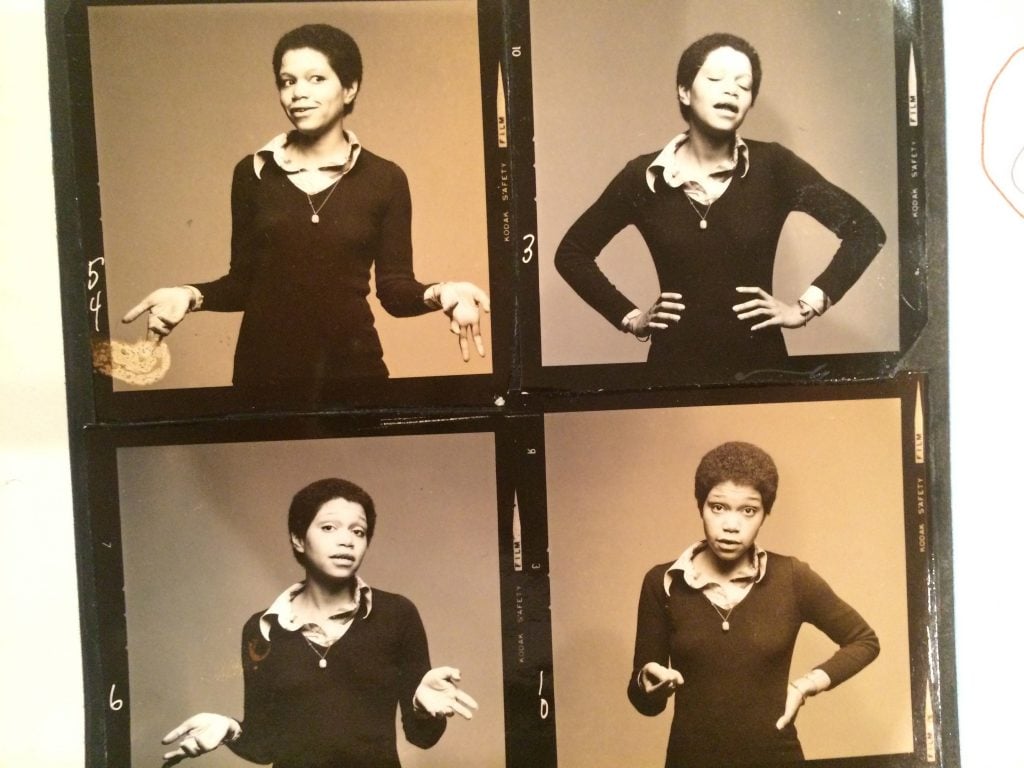

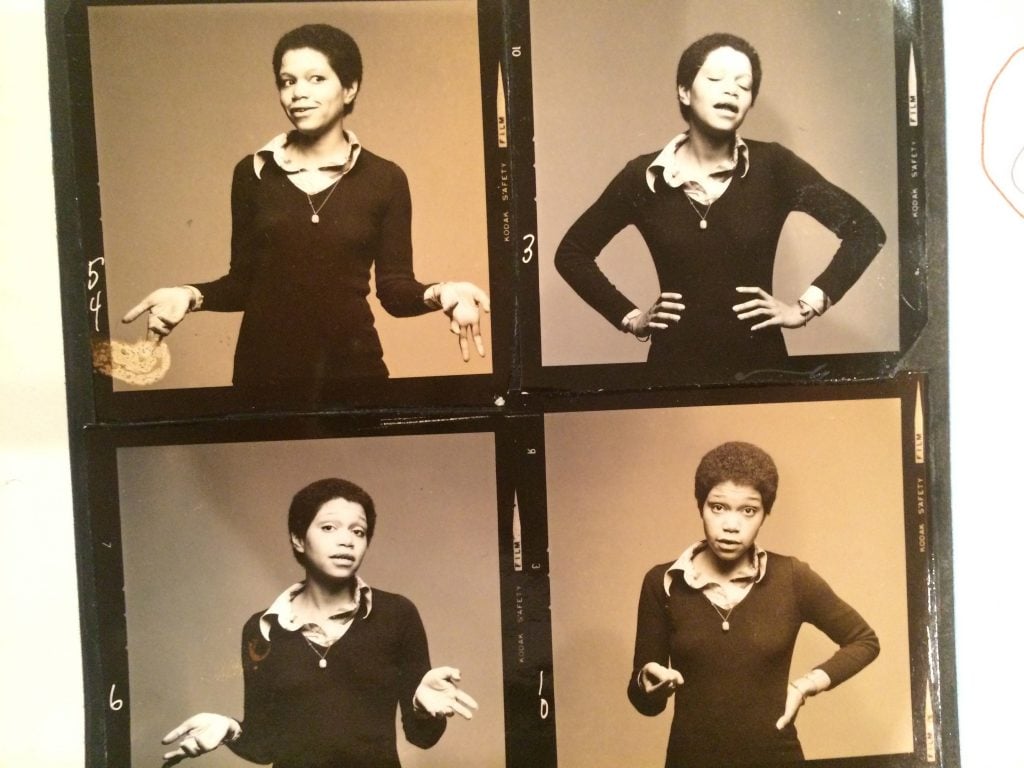

Linda Goode Bryant. Photo courtesy of Linda Goode Bryant.

I’d like to talk a little bit about community and the communities that Black artists had to build around themselves in order to work and to live—creating space, opportunities, and sharing resources. From what you’ve seen over the past 20 to 30 years, how has the community that Black artists built around themselves changed?

There was a time when artists got together to argue and debate about each other’s work. There was growth for each artist. Those artists that were participating, we were more like family. I don’t sense family in the generation of artists that have developed since. Back then, we all supported each other. My house was a house where artists could crash. Marie Brown was an editor and she was on the board of the Studio Museum for a long time. It was known that if you came to New York City and you needed a place to crash, you could crash at one of our houses; sometimes we’d swap people. We shared every resource we had in our pocket. We’d put it on the table so everybody could eat. Food was cheaper then. With a couple of bucks, you could make a meal that would feed everybody. I don’t sense that kind of community—and yes, part of that community was driven by our need to share resources to help us get through, but there’s something more than shared resources, there was a community. And in fact I’d say there was a family.

This series of interviews centers on artists whose work intersects with social practice. I’d say social practice is still a relatively unfamiliar concept to people outside of the art world. How do you define social practice art, and why is it important?

I think it’s just all art. I don’t use the phrase social practice because separating it causes people to make a distinction between art that has been determined by the market and everything else. Project Eats combining art, food, and life in communities comes from the same imagination that a painting comes from. Since I was a child, I have always been interested in making art and I was always interested in making art that had real-life consequences. So Project Eats for me is artwork and it’s artwork that is a living installation that has consequences day-to-day for people in communities that do not produce their own food. It goes back to defining your own terms. It actually goes back to a quote that David Hammons said: “Art is anything an artist makes.” And the second thing David has always believed is that you have to always be honest and you have to always be willing to walk away. I think that’s hard for a lot of people.

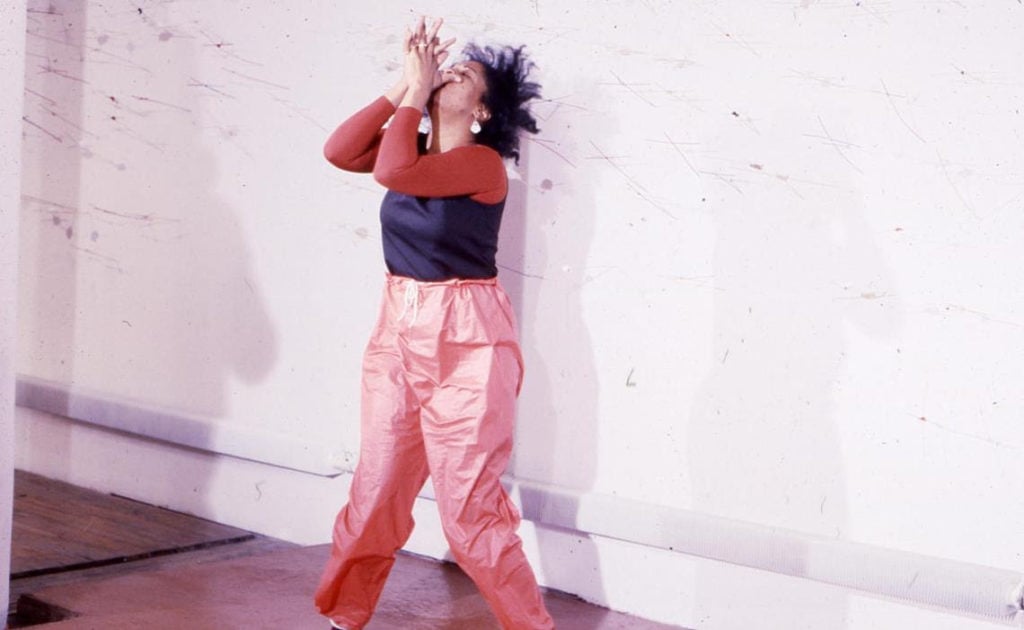

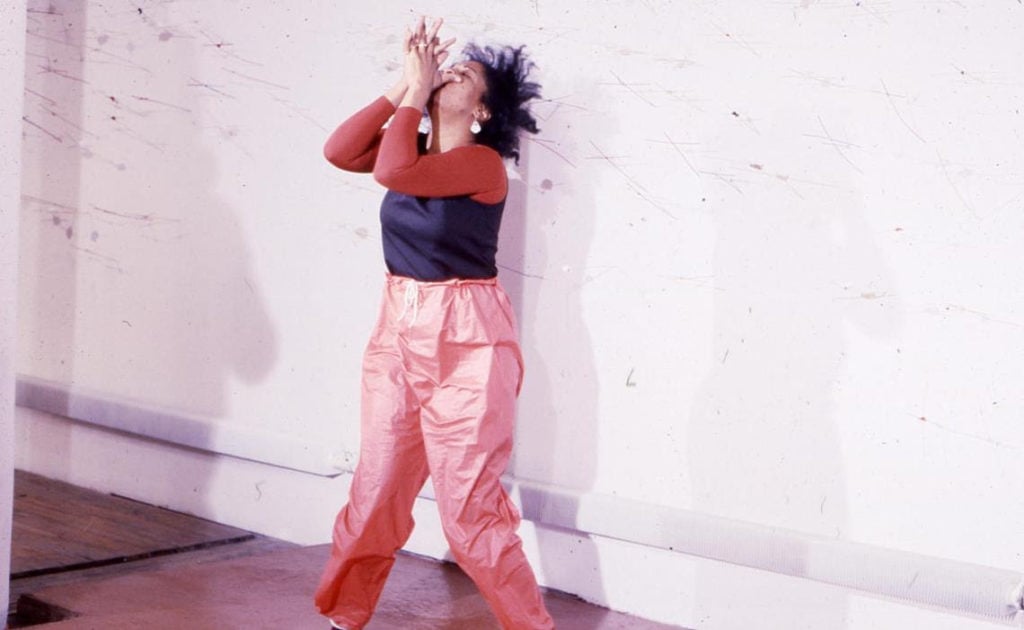

Senga Nengudi performing “Air Propo” at JAM, 1981. Courtesy Senga Nengudi and Lévy Gorvy.

Can you share with me the impetus for Project Eats? What was happening when you started it? What were you seeing that pushed you into this work?

There was a global food crisis in 2007 and 2008 and the crisis was caused by a rather severe increase in the price of cereal crops, so crops that have edible components to them like wheat and rice. That caused a rise in the price of food in grocery stores and at the time I was doing a project that was engaging with people who were legally disenfranchised or disenfranchised by the choice of not wanting to participate in the electoral process. I was working as an independent filmmaker, and I happened to be one of those people. I registered and voted for Jesse Jackson. Up until a certain point, I hadn’t voted in my adult life because the system doesn’t support me. In doing the documentary Flag Wars, I realized how unviable that not-voting strategy was.

We connected with organizations, families, individuals, public schools, and housing shelters working with people in communities across the country. I met mothers who were deciding not to eat breakfast and lunch so that they could buy pampers or feed their babies. We were documenting the impact this had on people’s lives and it occurred to me to look at it globally. In doing that, I came across this footage from Port-au-Prince in Haiti where people would eat mud pies with honey because they couldn’t afford food. As I was cutting and editing the footage, I’m sobbing. At some point I said, what can I do? This is insane. We should be able to grow our own food, even if it’s on concrete. And that’s how I started Project Eats.

In an interview with Marielle Ingram for i-D’s Darker Issue last year, you mentioned your childhood neighbors, the Dillards, and described Mrs. Dillard as being “radically Black,” and described how that influenced you. What does it mean to you to be radically Black?

What does it mean to be radically Black? Being truthful about the way you see things even when it differs from the way most people see it. Being informed and willing to discuss, debate, and implement social and political strategies based on what would likely be the most effective rather than the most expedient. Being who you are instead of what others expect you to be. Forceful yet sensitive. Determined and resilient. Caring and doing. These are qualities I seek in my life and my work.

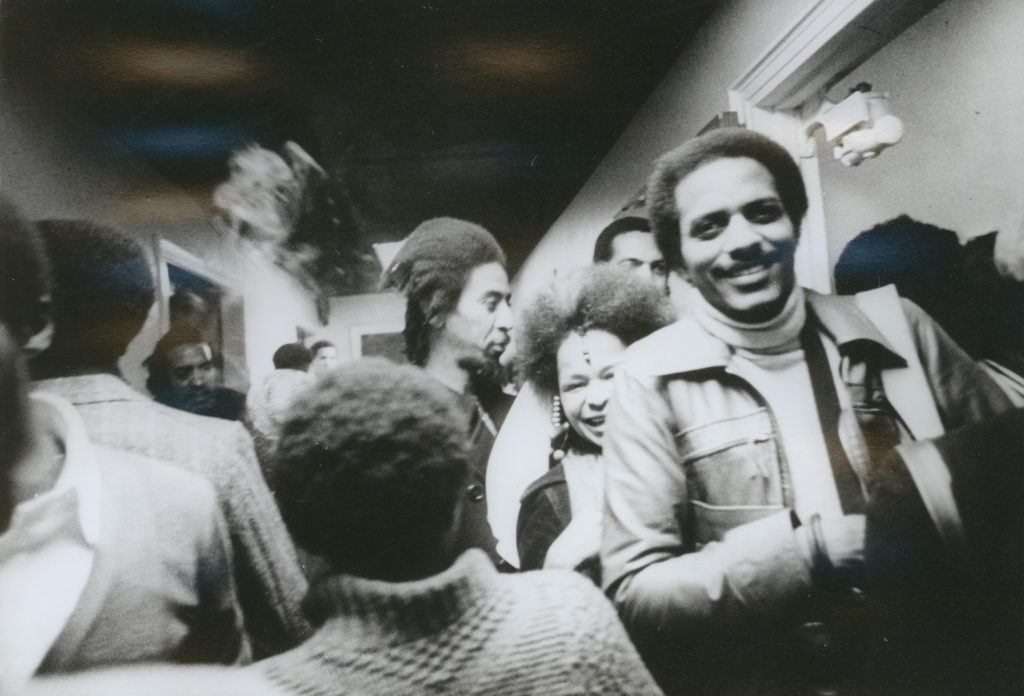

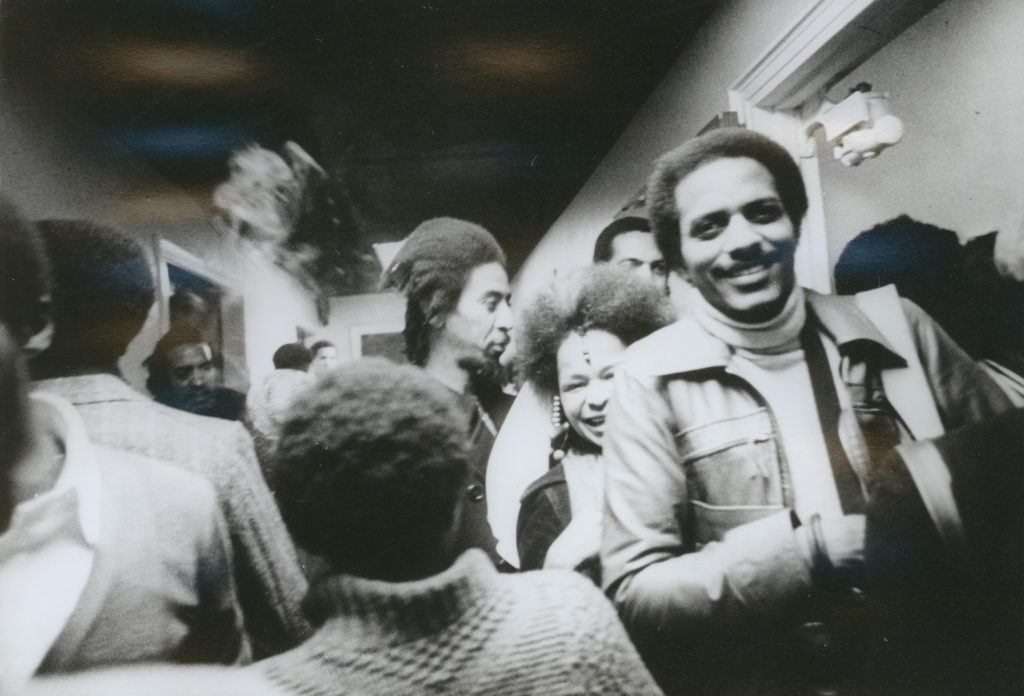

Barbara Mitchell (center right) and Tyrone Mitchell (far right) at the opening of the exhibition Synthesis, November 18, 1974. Photograph by Camille Billops. Courtesy the Hatch-Billops Collection, New York.

On the eve of the JAM exhibit at MoMA and after decades of art-making, what are you most excited about? What stirs you up, what motivates you, what continuously inspires you in your life today?

What excites and inspires me daily is our ability as Sapiens to imagine and make tangible the ideas we see in our mind’s eye for others to experience. Nothing has ever been better for me than transforming my ideas into tangible forms and being a parent. Both are difficult and seem impossible. Each requires ever-increasing levels of personal honesty and growth. Belief and trust that the intangible can be made tangible. Dogged determination, resilience, and inconceivable amounts of understanding and kindness. Together, they form the love and freedom we give to ourselves—and in a much better world than the one we have today, it’s a love and freedom we would generously share with others to ensure everyone is able to thrive.