Archaeology & History

Huge! The World’s Largest Neolithic Stone Circle

Constructing Avebury Henge required millions of hours of labor.

Outside the southern English village of Avebury, there’s a huddle of towering beech trees that local lore claims inspired J.R.R. Tolkien’s humanoid trees, the Ents. True or not, the village’s relationship with mysterious phenomena is ever-present: gouged into its surrounding chalky terrain is a monumental Neolithic arrangement known as Avebury Henge.

Today, the world’s largest stone circle is understood as part of a network of nearby megalithic structures including barrows, mounds, causewayed enclosures, and its more photogenic and famous cousin, Stonehenge. But it wasn’t until the 17th century that Avebury Henge truly entered the historical record.

This is partly due to scale. Yes, the presence of upturned sarsen stones was conspicuous, but it’s hard to conceptualize a 3,200-foot circle from ground level. Locals long thought its 30-foot deep ditches were natural features, hills perhaps, or else the vestiges of a disappeared river.

Avebury Stone Circle, aerial view. Photo: Getty Images.

As for the stones, the villagers’ relationship was largely destructive, either repurposing them as building materials, or, in fits of Christian puritanism, burning and sledgehammering perceived symbols of devil worship. This continued until the 18th century when William Stukeley, a pioneer in archaeology, surveyed the site, bemoaned the wanton plundering, and called for the protection of… well, what exactly?

Stukeley believed Avebury was Druid temple erected in 1860 B.C.E. He was incorrect, but closer than his contemporaries who claimed the Romans or King Arthur were responsible.

It took until the middle of the 20th century for archaeologists to confidently state that Neolithic farming communities incrementally built Avebury Henge between roughly 2850 and 2200 B.C.E. (making it contemporaneous with Stonehenge). Pollen and snail shell analysis shows humans had been present in the area since at least 7000 B.C.E., gradually transforming dense oak forests through slash and burn farming techniques.

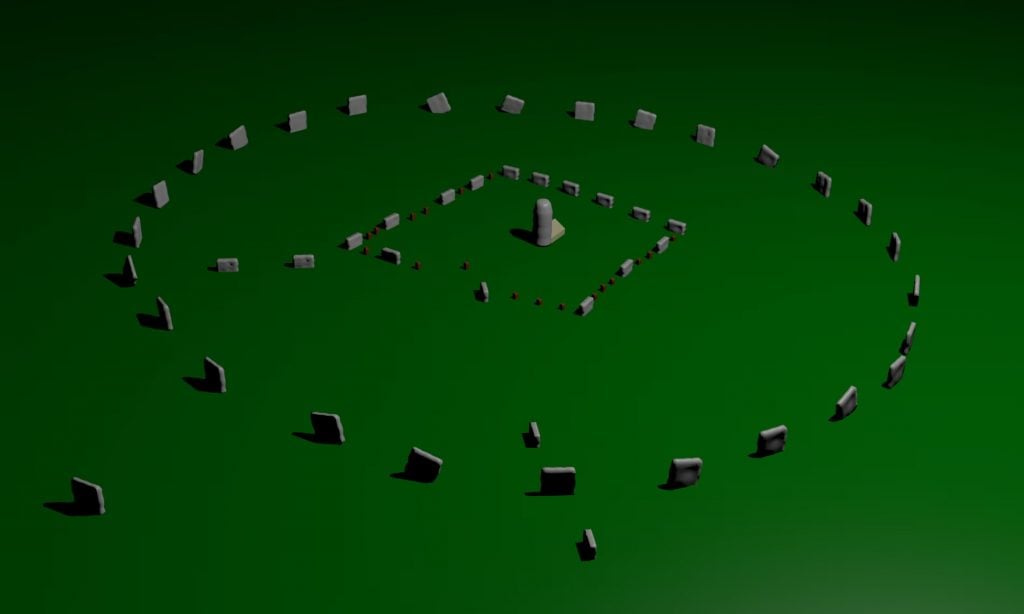

A model of the inner square at the south circle of Avebury Henge. Photo: courtesy Mark Gillings.

In a pattern echoed across Britain and Ireland, once these Neolithic peoples obtained relative food security, they got to building. They began with chambered tombs that venerated ancestors, such as at West Kennet Long Barrow, then moved onto megalithic stone circles. The scale and ambition of Avebury, however, dwarfs its peers.

First comes an outer ring, a 55-foot high bank accompanied by a ditch once lined with approximately 100 stones. There are entrances to the complex at the north, south, east, and west. Within this ring, there are two further stone circles, north and south, both measuring roughly 330 feet. The south circle is centered on a giant obelisk, long removed, surrounded by a square of stones. The north circle is centered on the Cove, a 100-tonne stone, so huge and seemingly immovable that scholars argue its presence in the landscape might have inspired Neolithic peoples to build around it.

To cut, dig, roll, and lift Avebury Henge into shape using only tools of stone, wood, and antler was a monumental task measuring millions of hours of labor. This speaks to the complex’s importance in the worldview of these Neolithic peoples. It stood as a fixed point in the land beneath the ever-shifting sun, stars, and moon—a way of tracking the cycle of the seasons perhaps, or signaling to the skyworld above.

Lines of standing sarsen stones forming the avenue leading away from Avebury. Photo: Geography Photos/ Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

Avebury was almost certainly a place for ritual activities. The circle is connected to two nearby mound sites via avenues of parallel stones and the lack of pottery, animal bone, or other Neolithic detritus suggests a sanctity, a place where everyday activities didn’t take place. We can imagine the fires and animal skins, the processions and chanting, but ultimately the purpose of Avebury and what took place there is unknowable, like asking someone with no knowledge of Christianity to conjure Sunday Mass from the hollow ruins of a church.

What the archaeological record does make clear, however, is that Avebury was under construction for hundreds of years, far longer than was necessary. Its importance was seemingly as much social as it was religious. It’s a place where disparate farming groups gathered, generation-after-generation, to meet, socialize, trade, and work on a communal project that was endless.

Sometimes, archaeology gets big. In Huge! we delve deep into the world’s largest, towering, most epic monuments. Who built them? How did they get there? Why so big?