Reviews

How an Intergenerational Cohort of Artists at an Icelandic Biennial Grappled with Notions of Darkness

The 11th edition of the Reykjavik art festival included artists Agnes Denes and Precious Okoyomon.

The 11th edition of the Reykjavik art festival included artists Agnes Denes and Precious Okoyomon.

Elizabeth Fullerton

Landing in Iceland in a gale as the winter darkness closes in, one has a primeval sense of being at the mercy of the elements. So, it feels somehow fitting that the curators of the artist-run Icelandic biennial “Sequences” selected the title “Can’t See,” for its 11th edition, which is on view at several locations until November 26. Not seeing, and darkness, have played a fundamental role in shaping Icelandic culture, said Sunna Ástþórsdóttir, director of the Living Art Museum, which is a co-founder institution of the biennial. “We have all these stories about mythological creatures, mysterious events, and hidden people, which is all to do with the brutality of living here,” she noted.

The curators—Marika Agu, Maria Arusoo, Kaarin Kivirähk, and Sten Ojavee—are part of a collective from the Estonian Centre for Contemporary Art. They have taken darkness as their starting point, both literally and metaphorically, by thinking about the wealth of life forms that humanity can’t perceive and the urgent issues we blindly refuse to recognize.

“The title applies to today’s world, with the ungraspable climate catastrophe on its way, but also war in Ukraine and pandemics, so darkness just seems very current,” said Kivirähk. “But it can also be read as the possibility that you might be using your imagination if you can’t see, so the theme embraces both doom and celebration.”

Edith Karlson, Can’t See (2023). Exhibition view from “Art in the Age of the Anthropocene” at Kumu Art Museum, Tallinn. Photo: Joosep Kivimäe

In pursuit of the imperceptible, the biennial is divided into four chapters: “Subterranean,” “Soil,” “Water,” and “Metaphysical Realm,” with exhibitions dedicated to these themes on show at four Reykjavik institutions, until November 26. The program brings together more than 50 Icelandic and international artists, in a lineup that includes Nigerian-American artists Precious Okoyomon and Dozie Kanu, as well as Edith Karlson, who will represent Estonia at the 2024 Venice Biennale.

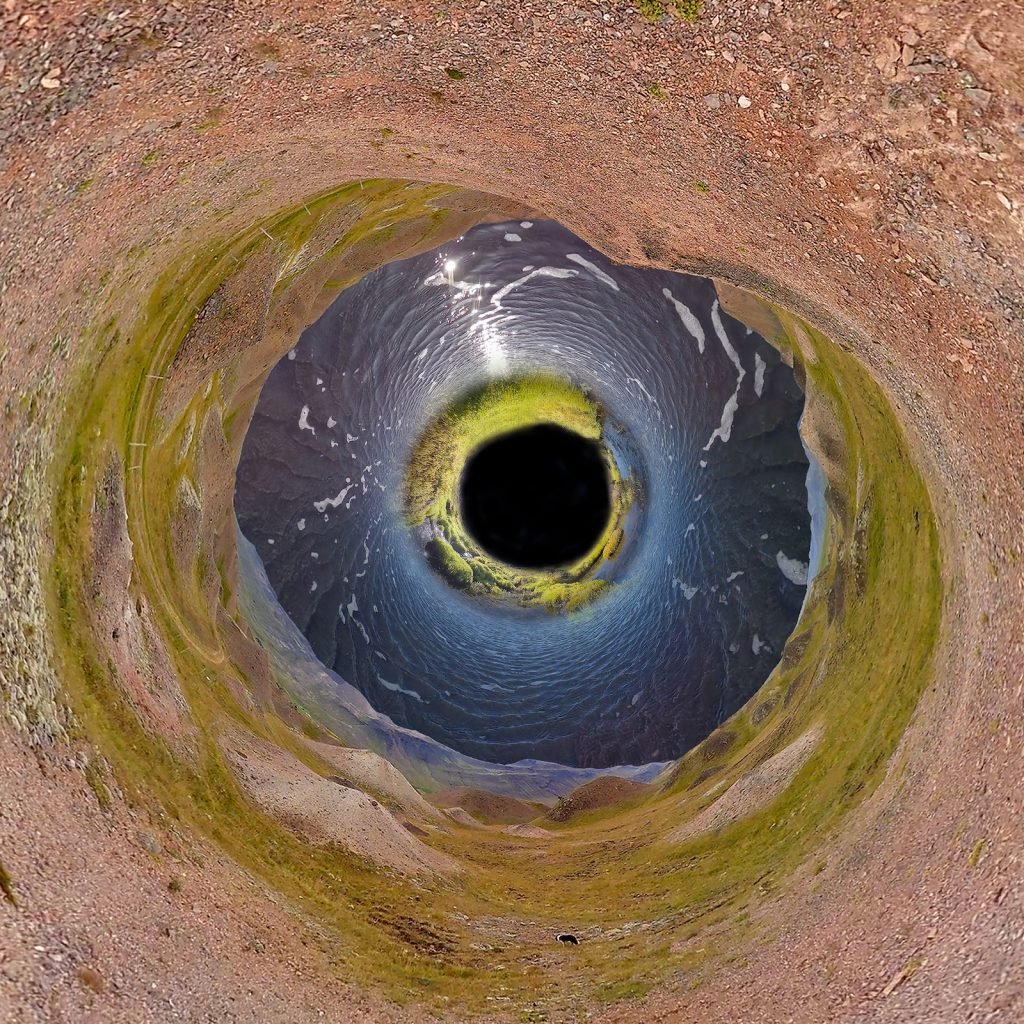

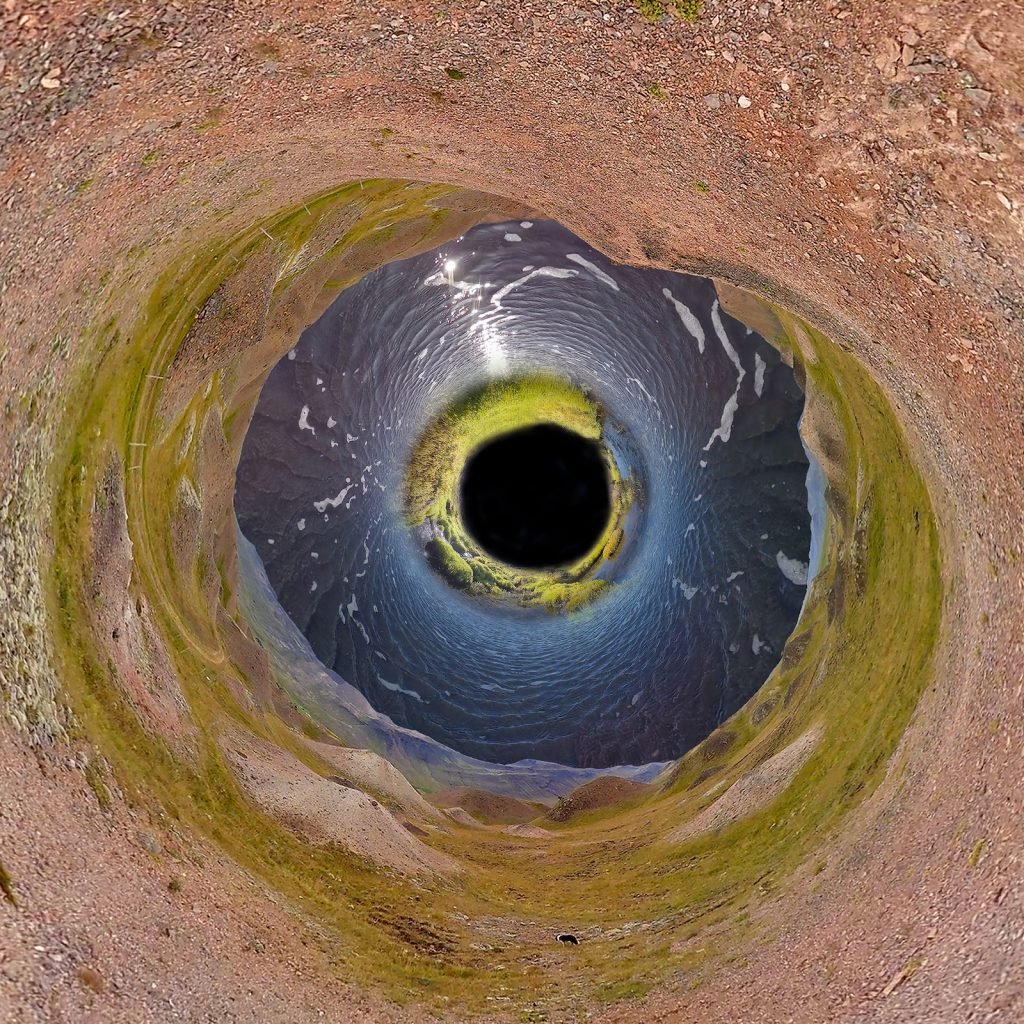

Okoyomon and Kanu have collaborated to create a wind installation in a lighthouse titled Fragmented sky – wind – fly giving presence to wind (2023), while Karlson’s mercreature sculpture, Can’t See (2023) contributed to the biennial’s title. From Iceland there’s a huge diversity of offerings, including Hrund Atladóttir’s Black Whole (2023), a dizzying video and AI portal into nature, and Brák Jónsdóttir’s sculpture of a shiny cyborgian jellyfish, Turritopsis 2.0 (2023), which is inspired by an immortal species and fuses elements of porn and horror.

What makes “Sequences” distinctive is the bold dialogues set up across generations, between new commissions and works from museum collections. It might seem counterintuitive for a festival looking to push boundaries to incorporate museum loans and deceased or “outsider” artists, but it’s a thrilling aspect of the program and testament to the curators’ thorough research.

Grotta Lighthouse lit up at night, venue for Precious Okoyomon and Dozie Kanu’s installation, Reykjavik. Courtesy of Sequences XI

An example is the unlikely pairing of landscape paintings by Iceland’s art grandee Jóhannes Kjarval (1885-1972) with Þorgerður Ólafsdóttir’s multidisciplinary works based around Surtsey, a volcanic island that erupted off Iceland in 1963. These include her cast of what is believed to be the earliest fossilized human footprint on earth.

“I have loved Kjarval’s paintings since I was a child, but it hadn’t occurred to me that our works would coincide,” said Ólafsdóttir. “I love all the details in his paintings. They somehow resonated with the tiny particles of seaborne waste embedded in the footprint, so it was an unexpected but happy encounter.”

Installation view of Monika Czyzck’s installation “Can’t See”. Photo by Monika Czyzck

Perhaps unsurprisingly, many of the artworks in “Sequences” draw inspiration from Iceland’s magical geology and vivid folkloric tradition. In the “Subterranean” section, Finland-based artist Monika Czyżyk covered the windows with symbols and faces relating to creatures she saw in the stones, mountains and rivers, using a variety of earthy clay tones she found in the Icelandic wilderness.

Czyżyk’s paintings reverberate with Valgerður Briem’s (1914-2002) intricate ink drawings evoking cartographies or perhaps internal bodily landscapes. The common ground, according to Czyżyk, is a vision of the cosmos, earth and its materials as “alive.” The artist explained, “It feels like we are portraying hidden, speculative worlds, inspired by our surroundings, science, ecology and heliobiology.”

Besides Briem, the curators have given space to several women from the region who were undervalued in their lifetimes. One is Latvian artist Zenta Logina (1908-83), whose astonishingly dynamic depictions of the cosmos are represented in three relief paintings and a tapestry. A particular revelation was Estonian artist Elo-Reet Järv (1939-2018), with her fantastical leather sculptures, Self Portrait as a Dragon and My Insectivorous Totem (both 1995), which appear to engage in a lively conversation with mischievous rock-and-stone creatures by Icelandic artist Gudrun Nielsen (1914-2000).

Elo-Reet Järv, Self Portrait as a Dragon (1995), installation view at Kling and Bang. Photo Maria Luiga

“Sequences” offers a rare and welcome glimpse into these regional scenes, which have had relatively little international exposure. “Something the Baltic and Iceland art scenes share is that being on the ‘edge of Europe,’ so far away from the big system of the art world, it feels like they are more self-sufficient,” said curator Maria Arusoo. “We don’t have a strong market, so it doesn’t dictate what’s happening and the artists are quite independent in their ideas.”

In terms of artists from further afield, the curators paid careful attention to find shared sensibilities with those closer to home.

In terms of artists from further afield, the curators paid careful attention to find shared sensibilities with those closer to home. These include Hungarian-born American artist Agnes Denes with six prints that challenge scientific notions of the world as fixed and rational; in these she presents the world mapped onto familiar objects like a snail’s shell or a hot dog (from her Isometric Systems in Isotropic Space – Map. Projections series, examples here from 1976-86), alongside her dreamy flying bird-pyramid works from 1994.

Also on view was Guatemalan artist Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa’s lyrical sound piece Songs of Extinct Birds That Were Previously Unknown to Science But Have Been Rediscovered Through Spiritist Sessions No. 1-3 (2015); and U.S. Fluxus artist and musician Benjamin Patterson’s zanily brilliant, posthumously produced work When Elephants Fight, It Is the Frogs That Suffer (2016–7), which interweaves frog croaks with human frog noises, spoken proverbs and political messages.

The strong performance program (which culminated on October 22) gives the festival an experimental injection. Among the standouts are Norwegian artist and virtuoso saxophonist Bendik Giske with Icelandic composer Ulfur Hansson, who has created an ethereal sound by activating strings with magnets stretched across a row of desks, effectively turning them into a giant harp.

Pola Sutryk’s “perpetual soup”, based on medieval recipe. Vikram Pradhan

Estonian performer and choreographer Johann Rosenberg gave a messy, gruesome Paul McCarthy-esque performance that was supposed to culminate in the release of imported flies, but they didn’t survive the Icelandic cold, to the audience’s relief. Less dramatic, but definitely more nurturing, is Polish chef and artist Pola Sutryk’s contribution of a “perpetual soup” for visitors, which she said was based on a recipe used in medieval inns, where a pot sat on the fire day and night, with new ingredients added. “As the festival progresses and new relationships build up, so the soup’s flavor is also building up,” she said.

Human connections may have been encouraged among visitors to “Sequences,” but our species is refreshingly absent from most of the artworks. “We tried to limit the human narration and human representation in the exhibition, to allow ourselves to imagine the world around us through the senses of a variety of species,” explained curator Sten Ojavee.

Stripping humans out of the picture feels natural in Iceland, away from the behemoth galleries and art fair carousel of big art capitals. In this strongly supportive community, the artists seem connected to the landscape in a way most western Europeans might find hard to comprehend. One has the impression of a thriving, self-reliant scene, driven by a sense of playfulness, joy and curiosity, quietly getting on with the business of making art.

More Trending Stories:

Four ‘Excellently Preserved’ Ancient Roman Swords Have Been Found in the Judean Desert