Art World

The New White Nationalism’s Sloppy Use of Art History, Decoded

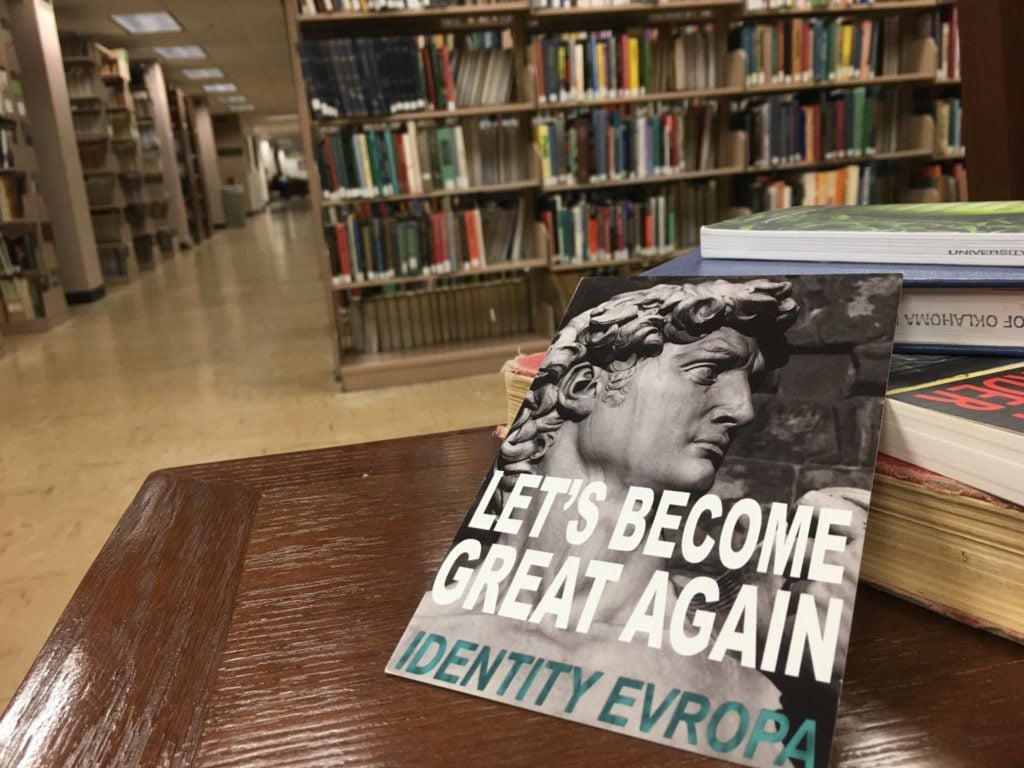

Identity Evropa has been terrorizing campuses across the country.

Identity Evropa has been terrorizing campuses across the country.

Ben Davis

Is Michelangelo’s David the new Pepe the Frog?

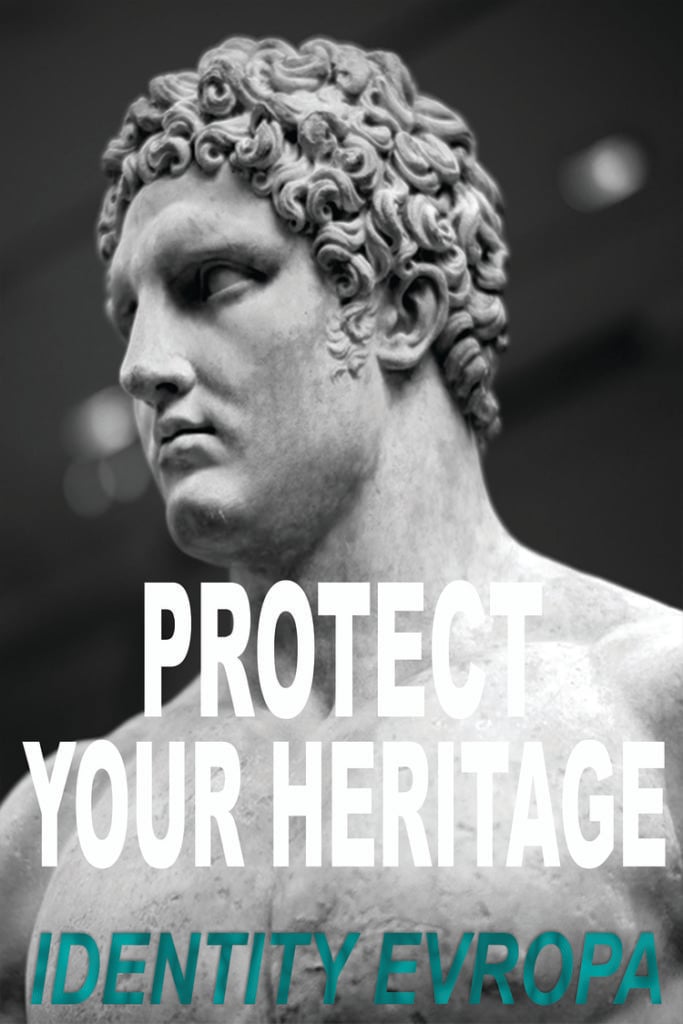

For months, posters featuring heroic black-and-white close-ups of classical sculpture, including the David, have been popping up at college campuses across the country. They could be confused with ads for an art-history survey course—were it not for the images being accompanied by slogans like “Serve Your People” and “Protect Your Heritage.”

Then there’s also the name of the group emblazoned at the bottom: “Identity Evropa,” a crypto-fascist, white supremacist organization.

In February, the posters appeared outside the offices of Valerie Grim, an African-American studies professor at Indiana University Bloomington, warranting a mention in the New York Times as evidence of a growing presence of white nationalist groups on college campuses.

Schools across the country have been targeted by Identity Evropa, from Kurtztown, Pennsylvania, Rapid City, South Dakota, and Hastings-on-Hudson, New York to the University of Washington in Seattle, the University of Chicago, and many others.

Last week, in an alarming incident, a fistfight broke out in the galleries of the Minneapolis Institute of Art between anti-fascist organizers and a group that was thought to be organizing a “white culture” meet-up at the museum. Identity Evropa was among the groups alleged to be involved—though, to my knowledge, that has yet to be confirmed.

What to make of this unsettling new symbolism?

Founded last year, Identity Evropa is a relatively new group, buoyed by the waves of nativism and racism attending Donald Trump’s candidacy. The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), a hate watchdog, has listed the group’s founder, Nathan Damigo, as one of the three pillars of the alt-right’s new push to attract youth, alongside Milo Yiannopoulos, the now-disgraced provocateur and Breitbart editor, and Richard Spencer, who coined the term “alt-right” itself.

The SPLC describes Identity Evropa as a “reimagining of the now-defunct National Youth Front, the youth arm of the white nationalist American Freedom Party.” The group makes its pitch to alienated young white men looking for a sense of identity and purpose: “We Are the Future,” the Identity Evropa homepage declares, emblazoning the claim over a stock photograph of a sunset; “Join Us,” it exhorts elsewhere, over a photo of Damigo and his cohort. “Become part of something bigger than yourself.”

Screenshot detail from the Identity Evropa website.

I gather that Identity Evropa is somewhat unique among a new wave of hard-right organizations in attempting to organize in the meat world as opposed to online space. #ProjectSiege, the group’s current campus-postering campaign, is the main representation of that impulse, thus far.

In the current charged climate, the posters have sparked considerable alarm—though it bears mentioning that, by Damigo’s own admission to CNN, the group remains very small, with a few dozen members across the country at most. Indeed, when you really look at the posters, their design—white-over-white text, slightly squashed images—indicates amateurishness rather than massive sophistication.

Still, two things about their particular use of European art are worth noting.

Richard Spencer was infamously seen at a conference last year declaring “Hail Trump! Hail our people! Hail victory!” (that last being literally the English translation of “Sieg Heil,” the Nazi salute). Members of Identity Evropa were in attendance at this gathering, blogging of the experience, “We have, without a doubt, ‘made it.'”

Nevertheless, this new crop of white power activists style themselves as “identitiarians,” bridling at the label “white supremacist.” They have consciously sought to distinguish themselves from old-school neo-Nazi imagery in an effort to take advantage of the Trump moment and mainstream their movement on campuses.

In this context, it’s hard to say whether Identity Evropa’s invocation of classical art is a canny attempt to sex up hate or an unforced error. Because the symbolism of antiquity is Fascist Aesthetics 101, as any student of modern art will know.

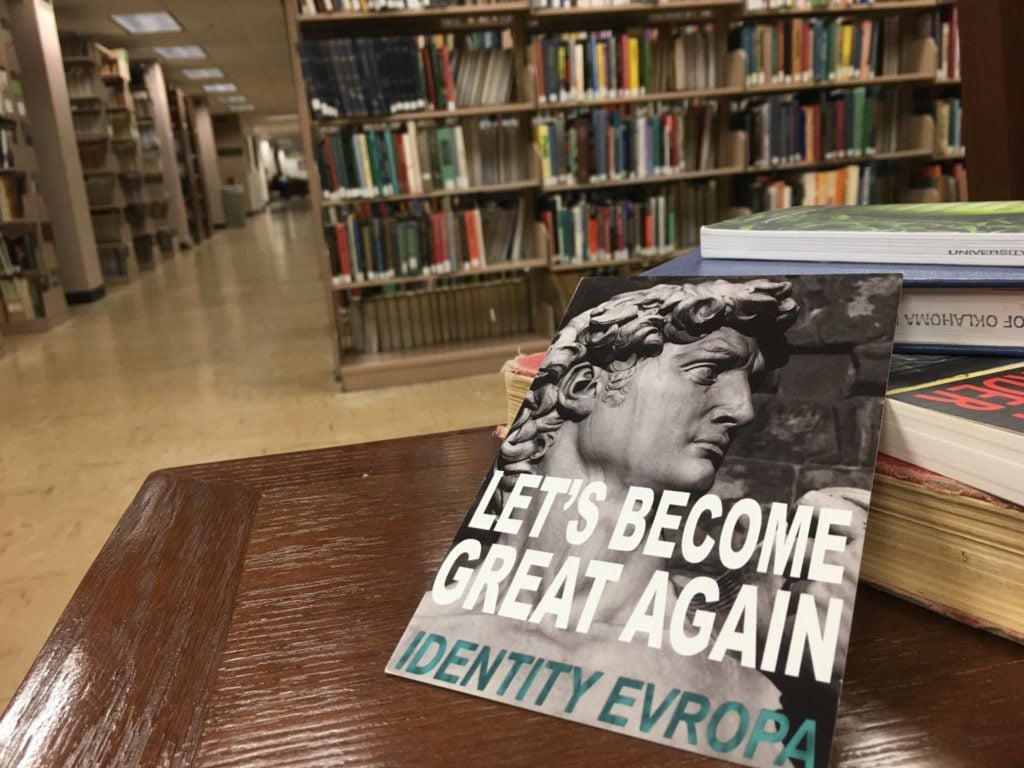

Mussolini, the guy who coined the term “fascism,” looked to the Roman empire as a symbol of Italian greatness. Hitler branded the more outré art of his day—Expressionism, Dadaism, and the rest—as “Degenerate.” But he loved classical sculpture!

Hitler with a Statue of a Discus Thrower. Photo by Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images.

“Without the classical tradition, the Nazi visual ideology would have been rather different,” Rolf Michael Schneider of Ludwig Maximilian University told the BBC a few years ago. “The perfect Aryan body, the white color [of the marble], the beautiful, ideal white male: to put it very bluntly, it became a kind of image of the Herrenrasse or ‘master race’—that’s what the Nazis called themselves and the Germans.”

Now-fallen alt-right star Milo Yiannopoulos positioned himself as a new-model punk, getting a lot of mileage out of the novelty of framing mockery of women and minorities as outrageous performance art. A broad section of the new right has preferred a 4chan-inspired language of slacker memes and scatological humor.

Identity Evropa’s posters swing all the way back in the other direction. Essentially, when you see these posters, you think, “Wow… they’re really going there!”

Still, is there any meaning to the specific artworks that Identity Evropa puts to work for the cause? Let’s see.

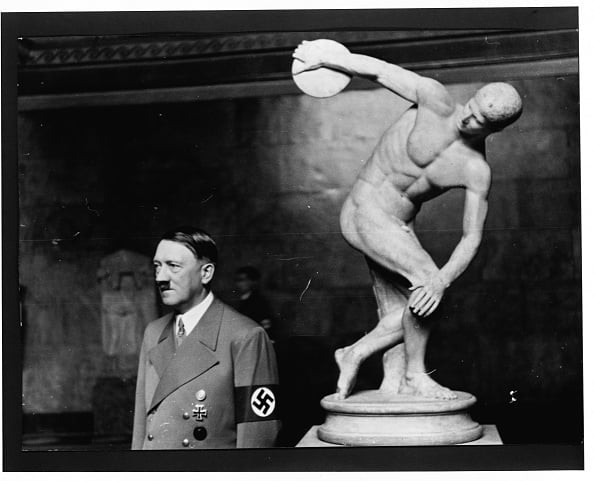

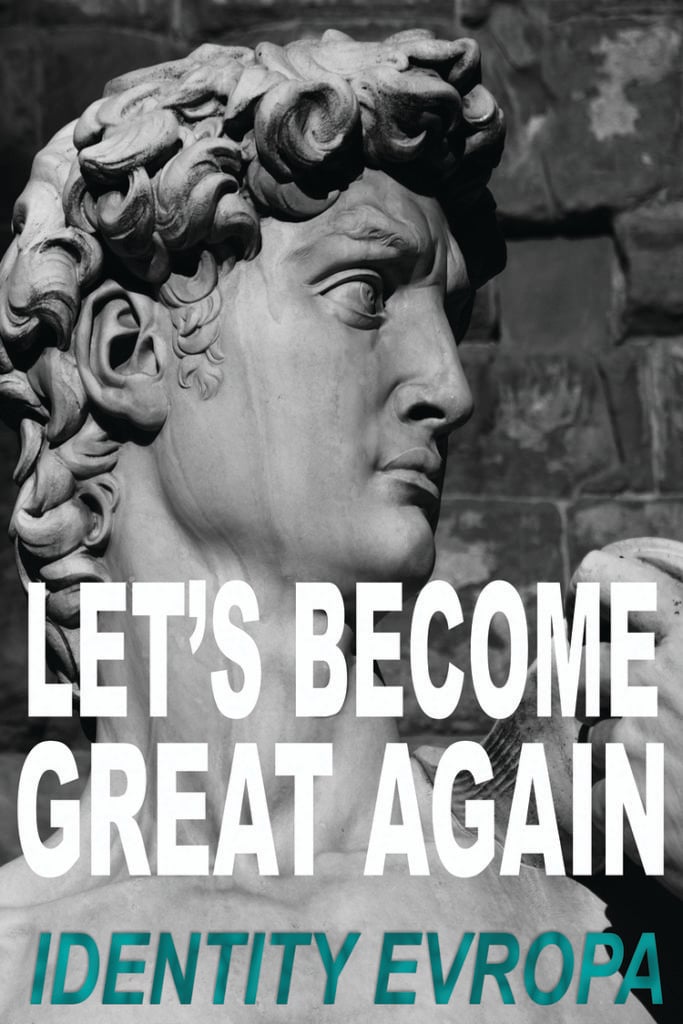

Identity Evropa poster.

There’s the David, with the slogan “Let’s Become Great Again,” which makes some kind of sense, evoking both Trump’s “Make America Great Again” and the Italian Renaissance. (American Renaissance was the name of a white nationalist publication, whose editor, Jared Taylor, is quoted on the Identity Evropa site as an inspiration.)

Identity Evropa poster.

Then there’s the Apollo Belvedere (ca. 120–140 AD), now in the Vatican Museums, and a Marble Statue of Youthful Hercules (69–96 AD), from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, both with a long history of representing a heroic ideal. (Incidentally, I tracked down the image source for the latter, a photo by Joe Josephs of Young Hercules at the Met posted to Flickr. In an email, Josephs professed horror at having his work used for a racist meme.)

Identity Evropa poster.

The garlanded head of Julius Caesar is a detail of a work by classical French sculptor Nicolas Coustou (1658-1733), now in the Louvre. Commissioned for Versailles in 1696, the sculpture was conceived as a stylish symbol of “noble authority,” which is how it is put to work here, with the text “Serve Your People.” (The historical Julius Caesar, of course, is known for having a populist touch, being the subject of a personality cult, and playing a starring role in the crises that caused the Roman Republic to degenerate into autocracy…)

Identity Evropa poster.

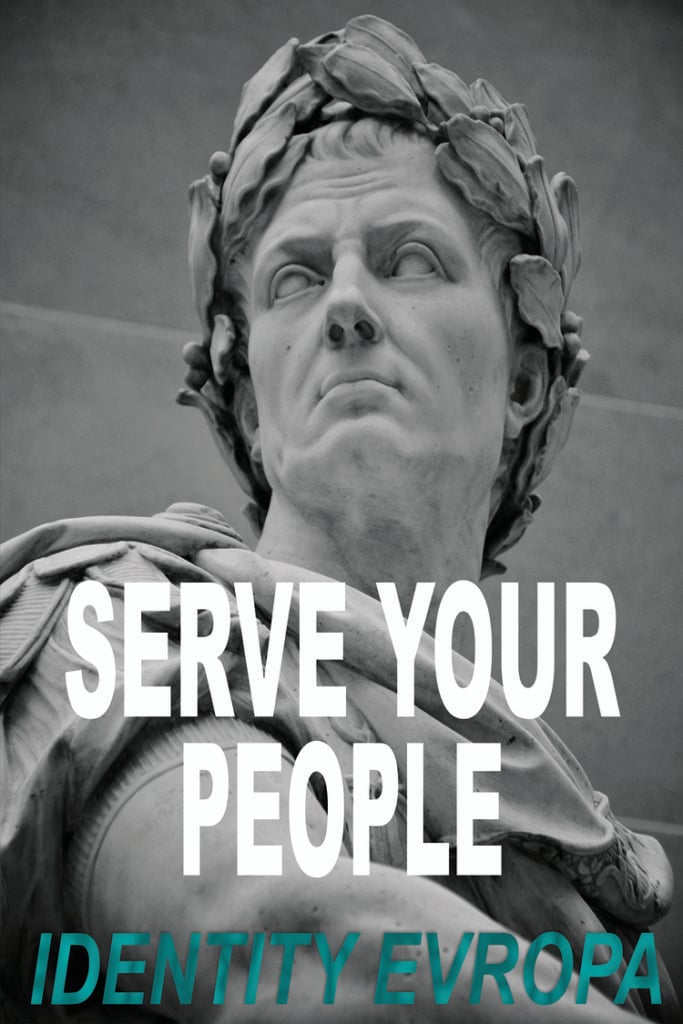

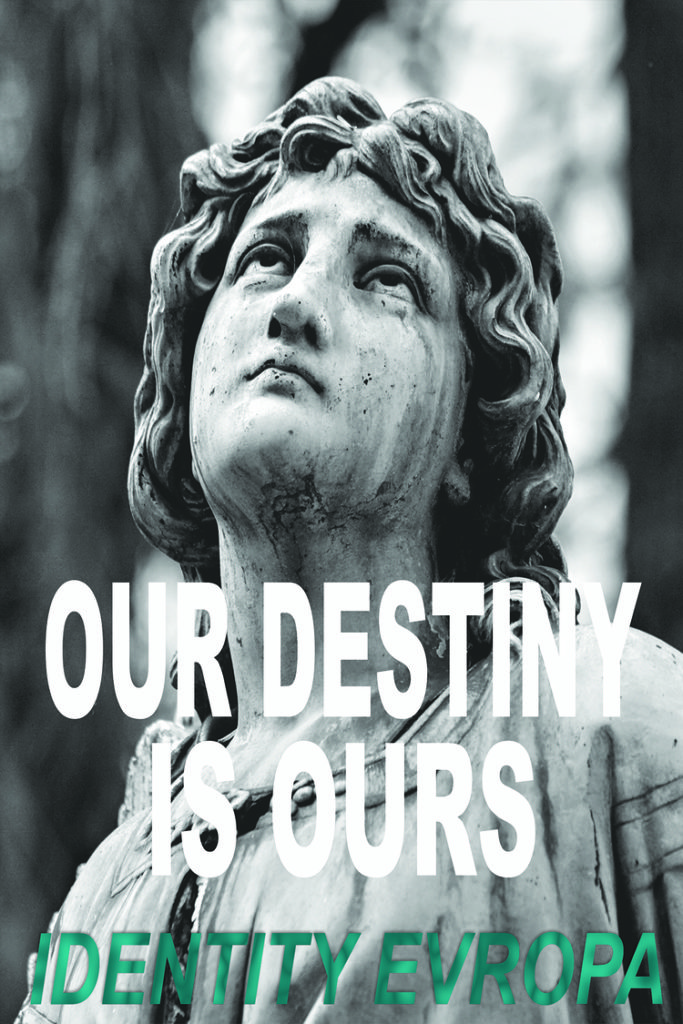

It is, however, the fifth sculpture here that is most interesting: an enigmatic figure with upturned eyes and the caption “Our Destiny Is Ours.” This sculpture looks familiar… without actually being familiar to me.

Identity Evropa poster.

After some extensive tooling around on the internet, I determined that this is a cropped detail of a photo of a funerary sculpture, an angel sited in the historic Old Cemetery in the small German town of Saarlouis.

Now, perhaps this image has some kind of mystical significance for white “identitarians” that I don’t know about. But art-historically, it’s not in the same league as the David or the Apollo Belvedere. Given its current use, it might be interesting to note that Saarlouis’s Old Cemetery is as well-known for its Jewish section as it is for its statuary.

Angel sculpture located in the Old Cemetery, Saarlouis. Image via Wikipedia.

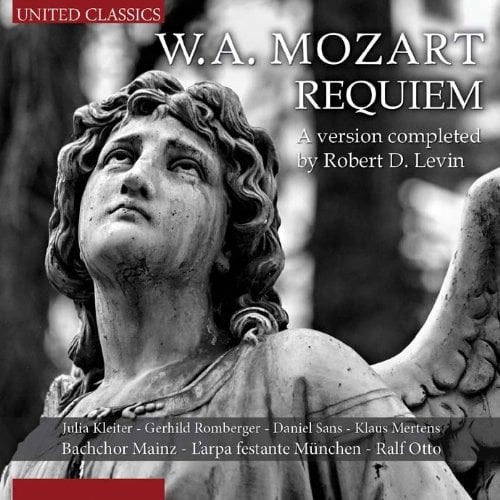

The exact same “sad angel” source photo has been put to work for a variety of purposes suggesting “divine European culture”—for instance, as the cover of a United Classics edition of Mozart’s Requiem. The best guess is that it is invoked by Identity Evropa, not because of what it actually represents, but because it just looks evocative of the right thing, which is probably ultimately true of all the other artworks here too.

The United Classics edition of Mozart, which uses the same photo as Identity Evropa.

Which kind of undercuts their whole project, when you think about it.

In a creepy video from the National Policy Institute touted on the Identity Evropa website, Richard Spencer lays out his “identitarian” agenda: “Our ancestors had a very strong sense of their identity. They could say, ‘I’m a Roman,’ ‘I’m a Saxon,’ ‘I’m a Dane.’ Some could say, ‘I’m a European.’ To be exiled from their communities would have been a fate worse than death.”

A bit later, in full blood-and-soil mode, Spencer adds, “Who are we? We aren’t just white. White is a checkbox on a census form. We are part of the peoples, history, and spirit of Europe. This legacy stands in front of us as a gift and a challenge. For what our ancestors took for granted we must discover and we must renew.”

A defaced recruiting flyer for Identity Evropa hangs near Trump Tower on July 6, 2016 in Chicago, Illinois. Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images.

Identity Evropa’s posters evoke art as an example of this robust, rooted tradition of European culture, one that it promises its audience that it can help them “discover and renew.”

But when you look into the sources, the images themselves suggest an awareness of this culture that doesn’t go much deeper than visual cliché. Instead, what you find is a hodgepodge; an identity pieced together in internet forums, from tourist pictures and Google image searches; militant ignorance masquerading as tradition.