People

Imi Knoebel: From Monochrome to Full Color

"If you want to do something, to stay alive, you have to think of something radical."

Photo: courtesy Galerie Thomas Modern

"If you want to do something, to stay alive, you have to think of something radical."

Amah-Rose Abrams

Imi Knoebel’s highly influential oeuvre includes sculpture, painting, installation, and photography. A friend and contemporary of Blinky Palermo and a student of Joseph Beuys, Knoebel’s work also represents an important turning point in art history.

Born Klaus Wolf Kneel Knoebel, he first attended the Darmstadt Werkkunstschule in 1962 and enrolled in a course based on the pre-Bauhaus method taught by professors Johannes Itten and László Moholy-Nagy.

Imi Knoebel Zeichnung Nr. 19 (1991-16 -19) (1991)

Photo: courtesy Galerie Fahnemann

It was here that he met Rainer Griese, a fellow student. They quickly became fast friends, and were both so enamored with the work of the Suprematist Kazimir Malevich—particularly his seminal painting, Black Square (1915)—that they took to wearing unbuttoned capes, open shoes, and cut their hair to emulate their idol. They also changed their names to Imi & Imi, a shortened version of “Ich mit Ihm” (or “I with him”).

“I thought: everything has been done already,” Knoebel told the Guardian in a rare interview in 2015. “Yves Klein has painted his canvas blue, Lucio Fontana has cut slashes into his. What’s left? If you want to do something, to stay alive, you have to think of something at least as radical,” he added.

Imi Knoebel Untitled (1987)

Photo: courtesy Imi Knoebel Gelbes Hamburg (1999)

Photo: courtesy Michael Werner Kunsthandel

Imi & Imi discovered Joseph Beuys through a newspaper article detailing an event where the artist and teacher was attacked during a performance.

“We saw this art professor with a bloodied nose in the newspaper, holding up his hand in messianic fashion, and we said ‘We have to help that man,’ without knowing why he had been attacked,” Knoebel recalled to the Guardian

“We had absolutely no talent, but we mustered the courage to approach him—when there’s two of you, you only need half the courage—and told him we didn’t want to show him our art, we just wanted him to give us a room of our own. He was both taken aback and sold on our cheekiness,” said Knoebel of approaching Beuys for the first time.

Legend has it that the pair hitchhiked to Dusselfdorf to attend the academy and study under Beuys. There they were accepted, and given the keys to Beuys’ infamous “Raum 19” (room 19). It was in that room that Knoebel made what is believed to be his defining work: a modular structure compressing of cylinders, boards, and rectangles, that can be reconfigured in an infinite number of arrangements. The work, titled Raum 19, now exists in four iterations, one of which is on permanent view at Dia:Beacon.

Imi Knoebel Kinderstern (2005)

Photo: courtesy Phillips London

Knoeble attended the Dusseldorf Academy from 1964–1971, continuing to study under Joseph Beuys and thriving under his tutelage. During his time at the academy, Knoebel shared a studio with Blinky Palermo and attended classes with painter Jörg Immendorff and photographer Katharina Sieverding.

Knoebel worked mainly in drawing at this time—creating a staggering 250,000 A4 pencil drawings between 1966 and 1973, which he exhibited in sealed metal casings and were only available to view on demand. He also worked with light, projecting lines, squares, and crosses onto the walls of a gallery space. As he continued to maintain great flexibility as an artist by experimenting with different media, he gradually turned his attention to abstract monochrome painting.

The 1970s were hard on Knoebel: two of his best friends and closest collaborators died under tragic circumstances. Blinky Palermo died of a suspected drug overdose in 1977, and Imi Griese committed suicide in 1974. These experiences profoundly changed Knoebel, and he has said he has never fully recovered from these losses.

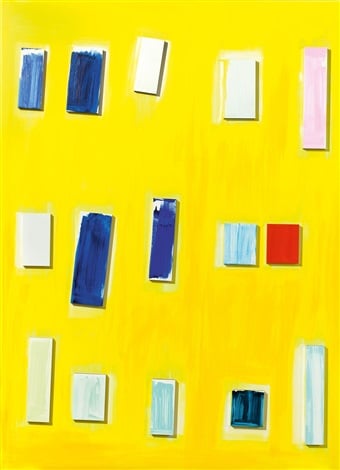

Imi Knoebel Gelbes Hamburg (1999)

Photo: courtesy Michael Werner Kunsthandel

Following Palermo’s untimely death, Knoebel created the series 24 Colors—For Blinky (1977) dedicated to his friend. Through this series he began, for the first time, to work primarily in color. This was an important turning point in his practice, as he applied his new explorations of color to the all the formal aspects of his work, echoing both Malevich and the American Minimalists.

As a tribute to his other dear friend, he also completed Eigentum Himmelreich (Property Kingdom of Heaven) (1983) for Griese.

Knoebel began to apply color to more sculptural works, creating varying shapes that half hung, half sat on the gallery floor. He also began to place blocks onto the surface of his works and, since 1990s, he has used metal cut into shapes that are then painted and positioned within his formal compositions.

He exhibited initially at documenta 5,6,7 and 8, then all over Europe and, more recently, at his gallery White Cube in London in 2015. His work is held in collections all over the world, such as Dia:Beacon in upstate New York, MoMA in Manhattan, and the National Museum of Contemporary Art Korea.

Knoebel’s work sells well at auction, although he has spoken openly against the increasingly high prices of the art market. Given the rapturous reception to his exhibition at White Cube, it’s certain that Knoebel still has a great amount to contribute to contemporary art, yet he remains humble.

“Having once thought I can never make a living from my work, I’m very happy that I no longer need to worry about whether it sells or not, or whether people like them or not,” he told the Guardian. “I just get on.”