Before things even got cooking in London last week for the 16th iteration of the Frieze Art Fair and the concomitant auctions, there was the monster Jean-Michel Basquiat exhibition hosted by Bernard Arnault at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris.

At the opening, a ticket as coveted as any, you could find market mavens Tico Mugrabi, Peter Brant, Patrick Seguin, and actor Owen Wilson—drafted into the art world by Tony Shafrazi (also on hand)—engaged in a round of liar’s poker. Made famous in Michael Lewis’s expose of the ruthless greed and gluttony of 1980s New York bond traders, liar’s poker is, according to Wikipedia, “an American bar game combining statistical reasoning with bluffing,” relating to the serial numbers on dollar bills. Mirroring the art market itself, a fury of notes rapidly exchanged hands.

Oddly, of the 120 Basquiats on view for the show, Brant’s were the only ones that carried a “No photography” proscription on the labels.

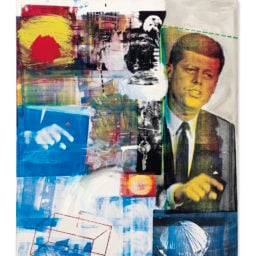

You might have heard of Yusaku Maezawa, a Japanese internet retailing tycoon and purchaser of a certain Basquiat painting, which has since been on a whirlwind publicity tour, soon to appear in an outlet near you. At the opening, Maezawa was more focused on chasing David Beckham (appearing Posh-less) for photo-ops than any of the art luminaries in the house. This makes perfect sense when you consider the positioning of art as part and parcel of an international, aspirational luxury advertising campaign. The art world as we know it is in the midst of a radical transformation as upside-down as any Baselitz composition.

For example, the Delfina Foundation is a London-based, independent non-profit facilitating the support of emerging artists since 2007. Now, by their own admission, they are the first program to formally host collectors in residence. I guess they are so endangered nowadays among the rampant “specu-lectors” that they need to be preserved before they end up taxidermied in a vitrine in a natural history museum. When youngish artists like Joe Bradley celebrate their sold-out London Gagosian show at Annabel’s with Virgil Abloh, a DJ, artist, and designer for Vuitton (see a pattern?), at prices ranging from $850,000 to $1.2 million, I guess collectors need all the help they can get. Fifteen years ago, I staged Joe’s first solo show and I couldn’t give them away (the priciest was all of $3,000).

Bring me their heads! I picked up this Josh Kline from 47 Canal’s booth.

Fair Fatigue or Fair Fatality?

The word “fair,” when used as a noun, refers to a periodic traveling show with games, rides, and farmers showing off their prized pigs—similar to a carnival. As an adjective, it gets a bit trickier. Art fairs are too ubiquitous to constitute a special occasion of any sort. That is the thing, they used to feel like something—what I’m not exactly sure—but at least something different, out of the ordinary. That’s no longer the case. Now it’s more like a chore, a bore and something to potentially ignore. Writing about fairs today is as hard as showing up.

Even in my front yard, I struggled to make it to Frieze and only did so at the last minute. Were it not for a class I had to teach for the art market studies department of the University of Zurich (sign up!), and for this column, I might have skipped it altogether.

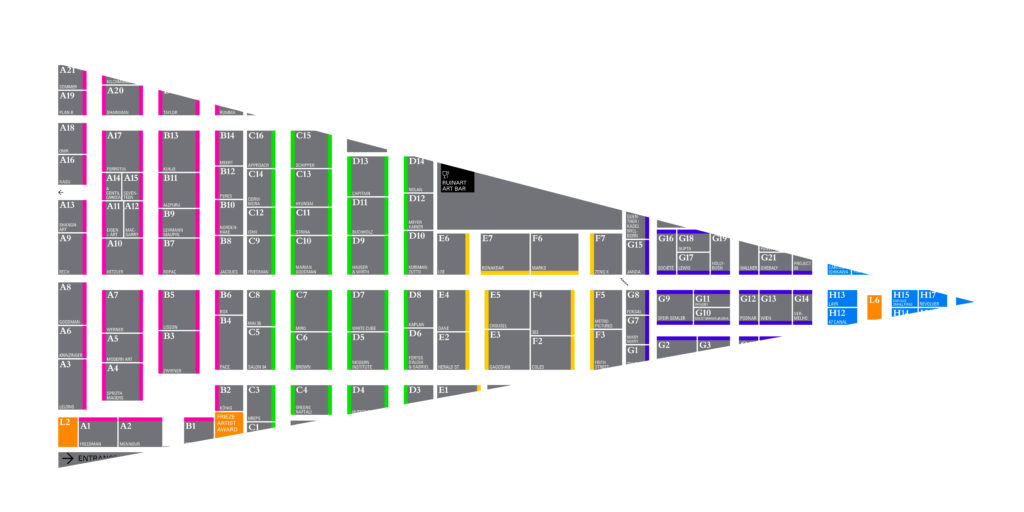

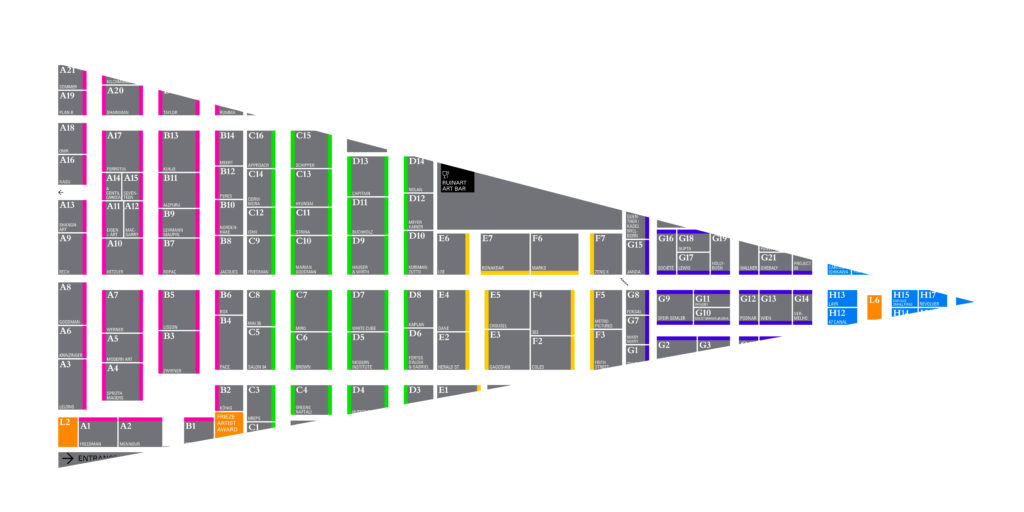

The triangulation of my diminishing attention span for Frieze, even before Frieze Masters. Photo: Kenny Schachter.

This sentiment is emblematic of a greater phenomenon: not so much fair fatigue as fair fatality. The forced march is becoming numbing and rote. Nick Koenigsknecht, director of the Berlin-based gallery Peres Projects, summed it up when I asked how he was managing, to which he sardonically replied, “I’m living the dream.” I share his pain. Typically, there’s a gravitational pull, a vibration emanating from the local convention center, that physically pulls you in when a big fair rolls into town. But it really seems to be dissipating of late, and I’m certain I’m not the only one that feels the disquiet. It’s not whether the fair’s good or bad—there’s always something to see (and buy)—but fairs seem exhausted, and indistinguishable from one another. Gallerist Emanuel Perrotin will do 23 fairs in the next year alone. Hello? I wish the market wasn’t buoyant enough to sustain the more than 250 a year, but so it goes.

A 1994 Mary Heilmann watercolor I bought from 303 Gallery. I consider myself lucky.

A common refrain since it came into existence in 2012 is that Frieze Masters is always better than the main fair. I beg to differ. That my attention span progressively diminishes as I make my way from one side of any given tent to the other, I’d rather save it for the more emerging material that was Frieze’s remit from the beginning. 303 Gallery’s Lisa Spellman, always as optimistic as she is successful, characterized the event as “Happy. Good vibes, good projects, good sales. Feels smaller and tighter, with some nice one-person exhibits.” I contributed to her endeavor by picking up a 1994 Mary Heilmann watercolor for $50,000. At a sprightly 78, with a museum track record the envy of many, I’d hardly classify Mary as up and coming, but her prices are, particularly in relation to her peers and even younger generations of painters. If she was a dude, I can assure you it would be different.

You can blame London’s Helly Nahmad for initiating the art fair booth as stage set when, in 2014, he constructed the imaginary dwelling of a French collector from 1968. Such flights of fancy have been steadily declining in quality and impact, from Hauser and Wirth’s ill-conceived 2017 creation of a fictional regional museum featuring golden coins emblazoned with a likeness of Iwan Wirth’s face to this year’s Dickinson Gallery recreation of Barbara Hepworth’s garden with little stick-on ladybugs in the stead of red dots to depict sales. There was only one ladybug visible, albeit on the most expensive sculpture, but dressing up booths in this manner is like a leaky valve taking away from the art and should come to a halt. Not to mention the waste of money and resources on senseless embellishment.

Dickinson Gallery’s Barbara Hepworth garden simulacrum. Photo: Kenny Schachter.

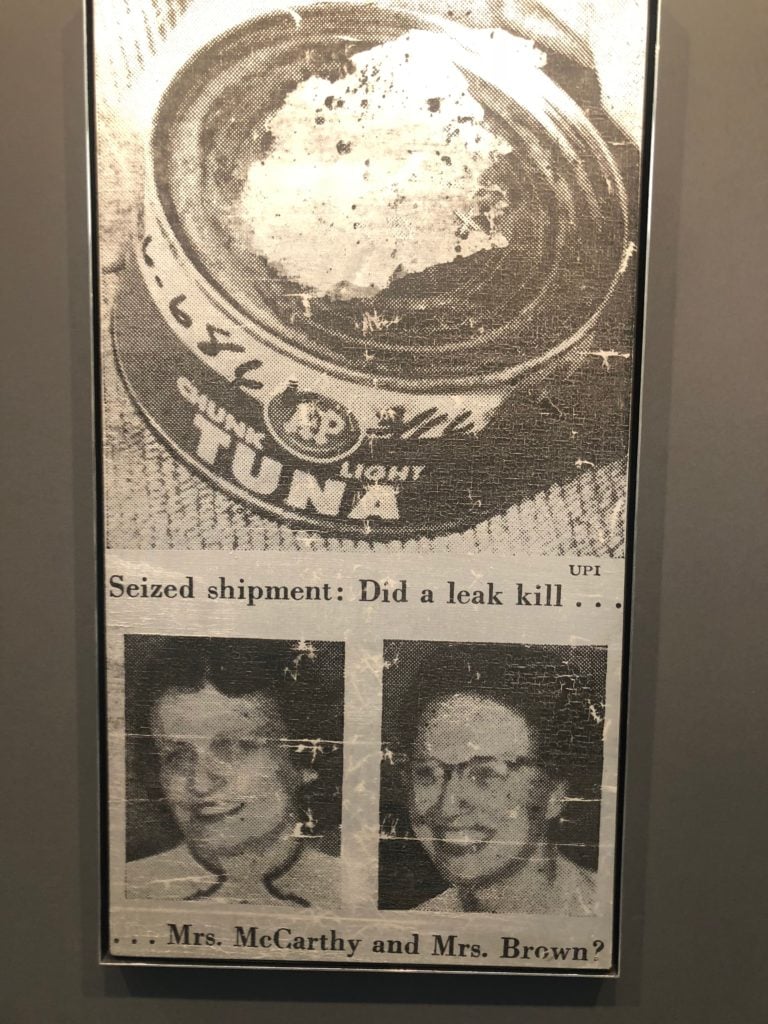

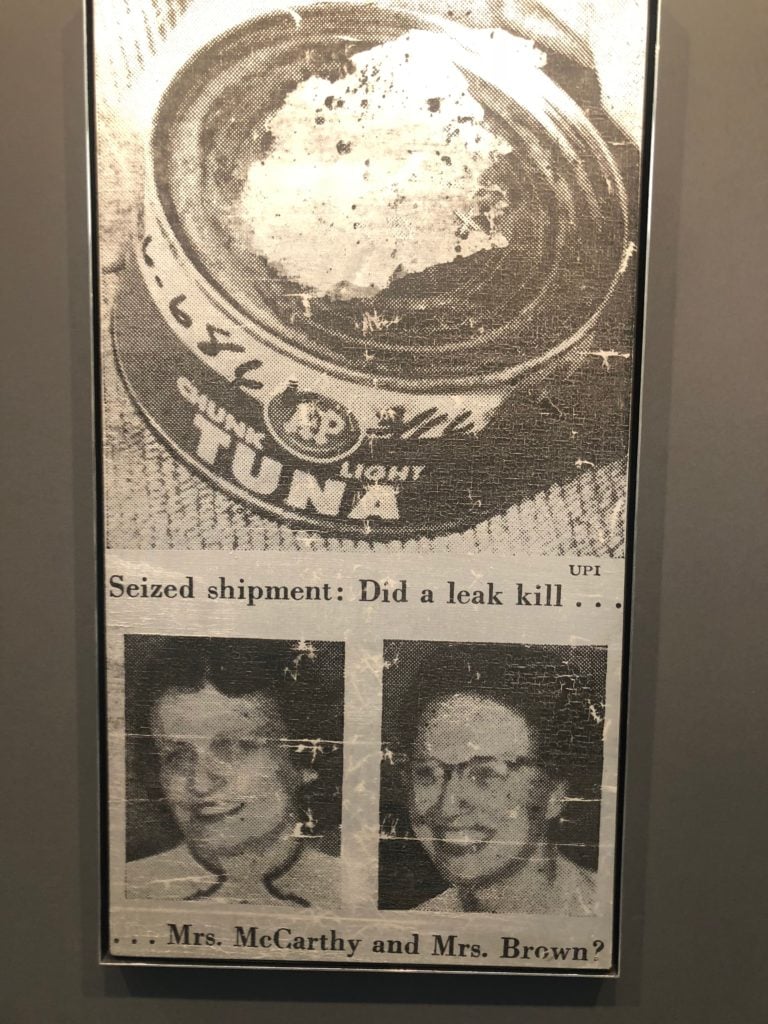

Some other random Frieze observations: Urs Fischer seems to manage to be everywhere at all times. Like a Manhattan deli that’s open 24/7, he appears to have an exhibit every month of the year. In spite of this, all of his paintings at Gagosian were sold with an asking price of $1.5 million each. Go figure. Another gallery with a young sought-after artist refused sales of coveted canvases unless you stepped up to a less desirable sculpture too. Then there was Castelli’s Warhol disaster painting that showed a can of contaminated tuna that was responsible for the deaths of two women. The $5 million work suffered a second disaster when it was subsequently submerged in water at some point, enduring damage apparent to the naked eye, after extensive restoration efforts. Why parade it in public?

Warhol’s double disaster tuna painting. Photo: Kenny Schachter.

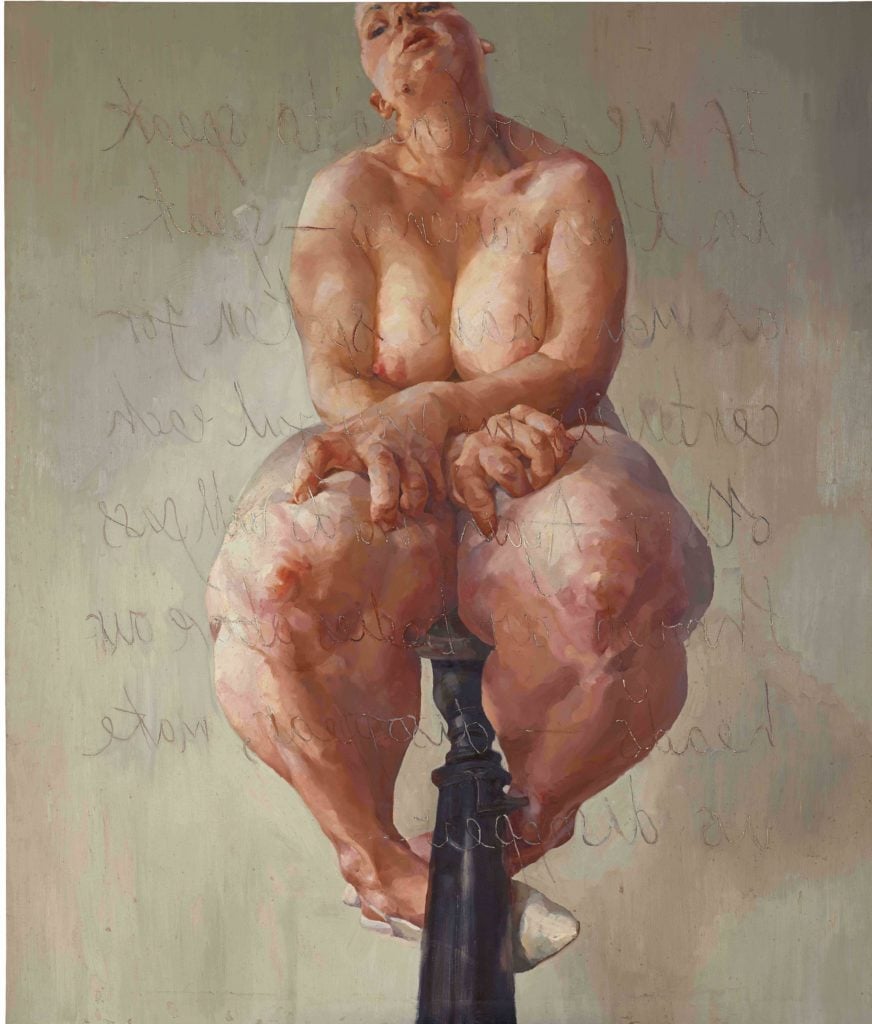

Jenny Saville’s Mystery Buyer

Speaking of water, another sea change that’s taken place is not so much the death of connoisseurship as its full-on replacement by an unquenchable desire for a hybrid of fashion, entertainment, and design. And art activism? Prior to the spate of London sales, the most queried lots were by Kaws and Banksy. Whatever is becoming of our art world? The other day, my bankers called and started the conversation, “We’ve had a big discussion on our team…” My stomach sank—in the days of complete (and utter) compliance, I could only fear the worst. But instead of any regulatory issues, the credit crew just wanted to know what I made of the Banksy prank. Indeed.

Protestations about speculation by an artist that sells everything he makes? And I thought I was plagued with irreconcilable conflicts of interest. Should we weep for his predicament of ever escalating prices? When the BBC came calling for my impressions of the spectacle, I fibbed that I witnessed it before speaking on the topic; I was present, but only for the first 10 lots of tedium. But I had seen more than enough. Dada for dollars. Smells like Maezawa’s (and Nike’s) brand of meta publicity and neo-narcissism.

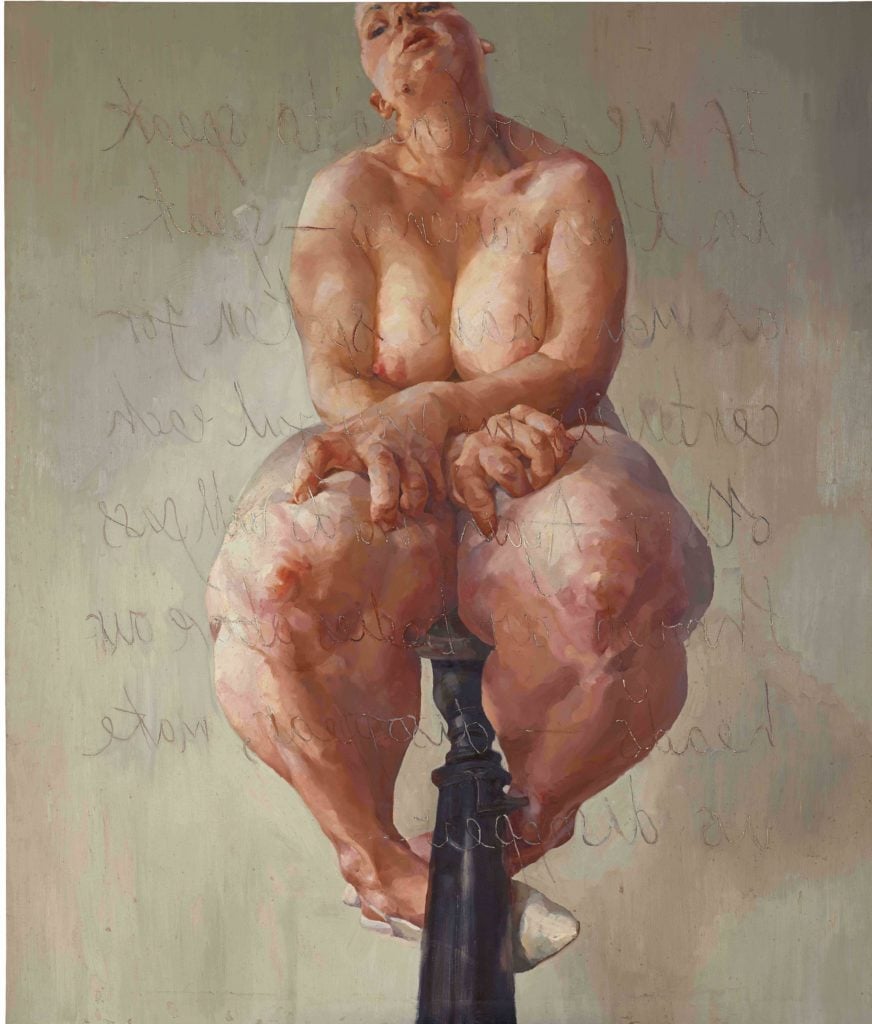

Want some breaking news? Secretive Russian investor Alex Greenberg (half-brother of German Kahn, co-founder of Alpha Bank and one of Russia’s richest) was the anonymous purchaser of Sotheby’s Jenny Saville painting for $12.4 million, nearly $3.5 million above her previous auction record. Go try and find a stitch about him on Google—you can’t. I thought I had a lousy seat assignment at the sale, in the penultimate row, but ever on the prowl, I couldn’t help but overhear from my position that the man behind me was seemingly bidding via phone on the Saville.

As I zeroed in on his convo, I snapped a couple cheeky snaps with my iPhone. His identity proved harder to uncover than Banksy’s. It wasn’t that no one knew who he was; rather, they didn’t want me to know. I’ve rarely seen so many cagey art dealers, so much so that I had to go outside the normal channels to earn my reporting stripes.

Jenny Saville, Propped (1992). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

And bid he did, in a prolonged pissing match with a punter on another phone line, that dragged on for at least 10 minutes. The hands of his (increasingly frustrated) advisor were slicing back and forth, bid after bid, indicating him to stop. Which he did. Over and over only to start again in micro increments of £50,000. Then another. He implored Sotheby’s Helena Newman, with whom he was on the line, to tell him “Who’s bidding against me?”

It was an expensive testosterone-fueled checkers match (chess would be too generous) of one-upmanship. Who won? The auction house and consignor—not sure how the combatants will fare at those lofty levels. You could sense the infectious tenseness, the spigot opening on the dopamine flow—until the bill arrives and buyer’s remorse sets in. “I’ll stop, I’ll stop,” Greenberg assured his hapless consultant. Yeah, right. When all was said and done, they could both be seen figuring out the fat auction premium on their phone calculators. A dose of reality.

“Family Guy” installation shot from Simon Lee Gallery, on view through October 20. Photo: Kenny Schachter.

A Little Shameless Self-Promotion

I wouldn’t be me if I didn’t mention my own curatorial misadventure at Simon Lee Gallery, open through October 20. It’s the fourth installment of exhibitions featuring the art of myself and my family (wife Ilona, and kids, Adrian, Kai, Gabriel, Sage). But in this instance it also appears alongside that of Christopher Wool, Rudolf Stingel, Rachel Harrison, Sarah Lucas, Franz West, and other leading lights. I am like the manager of the prototype boy band Menudo, but I can’t replace the members as they age, I’m stuck with them (and vice versa), however appealing the thought. Anyway, it’s great! See it! The best line of the week came from a director at Hauser and Wirth when I told her that I am a selling artist now. Without missing a beat, she replied, “Great, let us know when you’re a collector again.”

See you at FIAC in little more than a week. :/