Opinion

Why Did John Oliver Rip Off Debt Collective for His $15 Million Collection Stunt?

Last Week Tonight erases artist activism even as it capitalizes on it.

Last Week Tonight erases artist activism even as it capitalizes on it.

Ben Davis

On Sunday night, HBO host John Oliver scored his latest viral media victory with his segment on the US’s odious debt collection industry.

The team at Last Week Tonight had purchased $14.9 million in “distressed” medical debt for just $60,000. With the press of a big red button at the climax of the show, Oliver declared the debt forgiven, thus saving close to 9,000 Texans from being eternally hustled by unscrupulous debt collectors.

The segment is stirring and makes for some great Upworthy-style inspirational reblogging, the hook being that Oliver has offered the biggest television cash giveaway of all time, topping Oprah’s iconic car-giveaway stunt.

As it turns out, though, members of one very prominent anti-debt group, the artist-activists of the Debt Collective, are not happy. Indeed, in a blog post, they have accused Oliver’s debt segment of ripping them off.

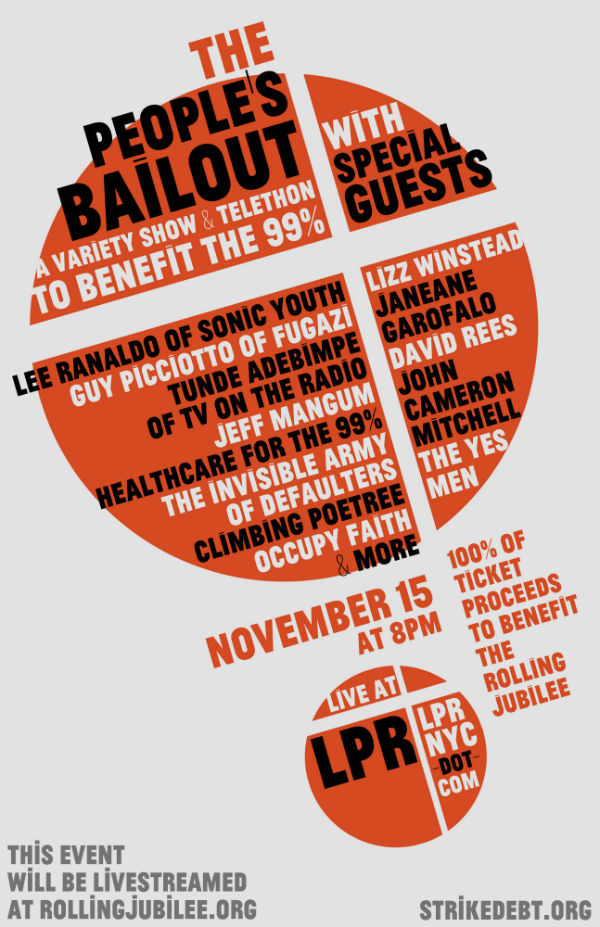

For those not familiar with the collective’s actions, here’s a little background: In 2012, a group of activists inspired by Occupy Wall Street came together to raise awareness about debt, forming what they called the Rolling Jubilee, a “Variety Show and Telethon to Benefit the 99 Percent” that raised funds to buy distressed medical debt. The inaugural event, held in New York at Le Poisson Rouge, featured an eclectic but star-studded lineup, advertising everyone from Lee Ranaldo of Sonic Youth, to John Cameron Mitchell of Hedwig and the Angry Inch fame, to the satirical activist-art stars, the Yes Men.

Poster for the Rolling Jubilee. Image: Courtesy Rolling Jubilee.

It was a success. “An initial wave of positive press led to nearly $200,000 in donations before the doors even opened, and by the end of the night, the live-streaming event had brought in enough funds to eliminate more than $5 million worth of debt,” reported New York magazine, calling it a “splashy debt-relief gala.”

So, the specific idea of buying up medical debt is not new. All this would seem like quibbling, perhaps—except that John Oliver’s team explicitly contacted the Debt Collective about reusing the idea.

In their blog post, the Collective explains that they were contacted a full eight months ago about the episode by Last Week Tonight‘s senior news researcher, Charles Wilson. Here is the description of the interaction:

Wilson told us Last Week Tonight was interested in reproducing our feat. Because LWT has previously done a good job of highlighting the outrageousness and injustice of various issues, we were under the impression they were interested in highlighting the mechanisms of oppression used by the creditor class as well as our ongoing organizing work to challenge these unjust arrangements. We spent hours on the phone and email with them explaining how we did our work and connecting them to other experts and resources.

At the last minute Wilson told us LWT did not want to associate themselves with the work of the Rolling Jubilee due to its roots in Occupy Wall Street. Instead John Oliver framed the debt buy as his idea: a giveaway to compete with Oprah. The lead researcher who worked on this segment invoked the cover of journalism to justify distancing themselves from our project.

Last Week Tonight is certainly the best of the recent crop of Daily Show clones, on account of its well-researched dives into tough issues and refreshingly agitational bent. The erasure of the Debt Collective connection, though, crystallizes some of the concerns I have about the show’s particular brand of rabble-rousing. (During Occupy Wall Street, incidentally, John Oliver’s Daily Show contribution to the public conversation about the movement consisted in finding the most outlandish participants and mocking them.)

When I first heard about the Rolling Jubilee back in 2012, I had all kinds of concerns. Why pay money to predatory loan companies, when the debt was odious in the first place? Why advocate for the People to pay instead of the unscrupulous corporations to blame in the first place? Wasn’t it all a rather ineffective symbolic drop-in-the-bucket?

Yet as the initiative developed after the initial Jubilee event, the organizers became clearer and clearer that the action was a tactic to raise awareness, not an overall strategy. As one told the Guardian in 2014, “The Rolling Jubilee doesn’t actually solve the problem. The Rolling Jubilee is a tactic and a valuable one because it exposes how debt operates.”

Debt Collective protester in New Orleans for 2015’s National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators conference

Photo: Courtesy Debt Collective

The Debt Collective has continued to do persistent organizing, keeping the issue in the spotlight with inventive actions. Last summer, for instance, the organization brought a group of indebted former students to the conference of the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators (NASFAA) in New Orleans to speak out. That action involved, among other things, a satirical art component straight out of the Yes Men playbook: a mock parade advertising the services of a fictitious Big Brother-like company, “Atopo,” offering tools that involved drone-based collections and biological implants for tracking debtors.

The ongoing efforts of the Debt Collective have had actual, material effect beyond its media presence. They have helped organize debt refusal by students of now-defunct Corinthian colleges, and connect students from other institutions like ITT Tech and the Art Institutes, the latter a rapaciously for-profit chain of art schools. These actions have already brought the issue to light, and even led to reforms: On the heels of the Corinthian debt strike, the Education Department announced in March that students of the chain were eligible for debt forgiveness.

The bottom line is that Oliver takes an issue that is the subject of ongoing, passionate activism, co-opts its most mediagenic parts, and then disappears the activist part. He ends his segment with a call for “reform,” but meaningful reform will likely need the pressure provided by the steady organizing of groups like the Debt Collective, rather than just a one-off TV segment (even one that’s on HBO). And instead of offering a tangible connection for people to get plugged into that work, he asks people to… share his video? It’s unclear what the end goal is, exactly.

There’s a fine line between shining a spotlight on the issue and hogging that spotlight for oneself—and in this case, that may be the difference between doing justice to the issue at hand.

(HBO did not immediately respond to a request for comment.)