People

‘We Need to Reinvent the ‘Us”: Kader Attia on How Art Might Help Turn the Tide Against the Far Right

Attia's "Mirrors of Emotion" has just opened at Lehmann Maupin.

Attia's "Mirrors of Emotion" has just opened at Lehmann Maupin.

Kate Brown

According to artist Kader Attia, we should all be feeling more emotional right now. That is, if we are to have any hope of defeating fascism, we better tap into our feelings, because strong sentiment is a weapon—and one currently being most effectively harnessed by the far right.

The Berlin-based artist’s exhibition at Lehmann Maupin, titled “Mirrors of Emotion,” presents an array of poignant works brimming with passion, sentiment, and sometimes pain. The ultimate end, he says, is to heal collective trauma and catalyze action, but the imagery he taps into is not always positive. The show features, for instance, pictures of dictators like Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels belting out hate-filled speeches. There is also a non-fiction film about police brutality, and another documentary-based piece about the phenomenon of the “ghost limb,” which occurs after someone has lost an arm or a leg but has the sensation that it is still there.

Attia and I meet in the courtyard of his studio in Berlin. It’s hot, and the news of the day is that Germany’s far-right party, the AfD, is set to make major gains in the suburb of Berlin (they came in second). The artist has just arrived from filming for a new work. Inside, his studio is filled wall to wall with books. He speaks quickly and passionately with an air of deep concern.

“I am very angry about the left. I think we have neglected too much because of a certain kind of snobbery,” says Attia. He argues that, since the 1990s, the left has abandoned the powerful need for collective healing and catharsis. “We need to reinvent the ‘us.’ The reason that fascism is rising everywhere is not only because we are living through a crisis of democracy, but also because people do not believe the media, and they do not believe the politicians either. Because people have abandoned politics, they have turned to spaces like social media. Far-right politicians have realized this, and they have figured out that their next El Dorado is here.”

Kader Attia’s Réfléchir la Mémoire / Reflecting Memory (film still #4), 2016. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul.

Attia is, for most intents and purposes, a political artist, though that hardly sums up the breadth of his work. He deals in questions of hegemony, social injustice, and trauma, and has been recently making work about how humanity repairs itself. His sculptures often appear to be quippy juxtapositions of European art canons with overlooked, non-Western narratives. In an earlier work called Oil and Sugar, the artist filmed crude oil pouring over white sugar cubes stacked to look the brick structure of Mecca, bringing two commodities that have bred international violence into one singular oozing pile of mush.

Attia is in a crucial position to be able to revise the distinctions between the fragile worlds of the East and West, Europe and the Global South. Born in France to an Algerian mother, he grew up between the North African country and Paris, and so the 48-year-old has both an intimate knowledge of and a critical distance from Western canons.

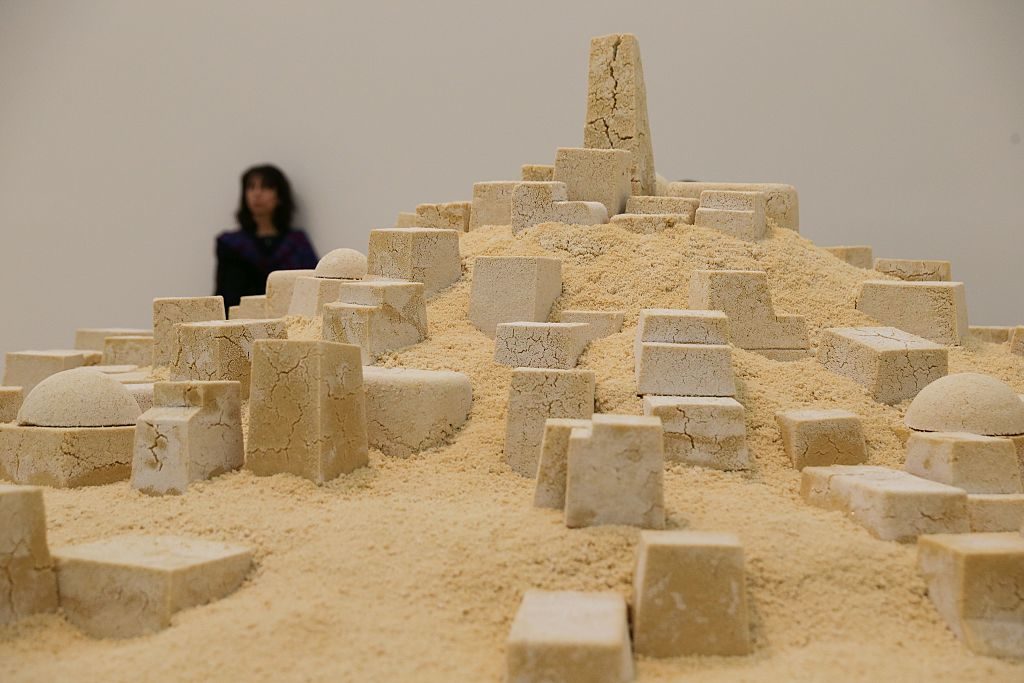

His unique perspective manifests in works that invert Western self-understanding: In Untitled (Ghardaïa) (2009), a scale model of the titular Algerian city made entirely of couscous, Attia sought to call attention to the appropriation of Middle Eastern and African architecture by the modernist architect Le Corbusier, showing the influence the East actually had on the West, despite the relations of domination fostered by colonialism.

Kader Attia’s Broken Face, Sick Mask in “The Disappearance of the fireflies” at The Collection Lambert at the Prison Sainte Anne in Avignon, southern France. Photo: Bertrand Langlois LANGLOIS/AFP/Getty Images.

What’s even more remarkable is that Attia has been making art about colonial realities and post-colonialism well before it became a trend. “‘Why are you working on colonialism?’, I remember some curators asking me. ‘These African countries have their independence, it’s over,'” he says. “Some galleries did not want to work with me because of my interest in the subject.”

Today, mainstream art institutions certainly have caught on. Attia has been featured in the most visible art shows across the world: the 12th Shanghai Biennial, the 12th Gwangju Biennial, last year’s Manifesta in Palermo, the 57th Venice Biennial, and documenta 13, among others.

But action on political issues cannot be confined to the art world. Rather, Attia says that activism is most efficient outside of the contemporary art context. That is why Attia founded La Colonie, a space for discourse and events near the immigrant-rich Gare du Nord in Paris in 2016. It’s also why he specifically does not want critics to conflate that gesture with his art practice. “I am not speaking as an artist with my work at La Colonie. It is not artwork and it will never be. We need to create spaces where we meet, where we can disagree.”

Attia argues that, in general, contemporary art is not the place where the most effective activism and progress can happen. “The majority of the analysis on colonialism and post-colonialism is not to be found in artworks,” he says. “It is in the debate.”

Kader Attia’s ‘Untitled’ (Gharda’a) at the Tate Modern in London. Photo: Daniel Leal-Olivas/AFP/Getty Images.

I ask him about what some might see as abuses of the cathartic through contemporary artworks. Chinese artist-activist Ai Weiwei, for instance, received scathing remarks when he posed as the drowned three-year-old Alan Kurdi, who died off of the Greek coastline in 2015. Earlier this year, a shipwrecked migrant boat that killed over 700 people was installed by Christoph Büchel at the Venice Biennale with not even a sentence of context or explanation.

“Some artists are perhaps working in a process of recycling pain. That is a dangerous weakness of contemporary art and it’s just a dead end,” says Attia.

His films, which are often up to an hour, challenge viewers to really sit with the subject matter. One work at Lehmann Maupin delves into the particular situation of racism in France. In The Body’s Legacies, Part 2: The Postcolonial Body, Attia interviews Théo Luhaka, a young man who was beaten and sexually assaulted by French police in 2017 when he was just 22, as well as others connected to that brutal case.

“The biggest problem that we have in France is that the left is not decolonial,” Attia says. “Many people do not understand that this is not just about the Algerian war and the Gulf war. This is about our universities, about issues of equality between men and women, between white and black.”

Kader Attia’s Réfléchir la Mémoire / Reflecting Memory (film still #1), 2016. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul.

At Lehmann Maupin, Attia’s wall of dictators and fascists is juxtaposed with the faces of famous and beloved performers. Billie Holiday, Edith Piaf, and Belgian singer Jacques Brel are coupled with faces representative of the deepest, most destructive forms of historical trauma. Attia calls the work The Field of Emotion.

“What, in mankind, has been able to compete with the magnetism of fascism? Artists,” says Attia. “It’s in human nature that we need someone who is the incarnation of someone we love and someone we hate.”

Inside his studio he pulls out a photocopied image showing someone in the audience at a concert, clutching his head and weeping with emotion. The expression is so intense as to be ambiguous. This is why Attia thinks that music, dance, and performance are the best formats for catalyzing the collective. Each of these forms offers an experience of being present among others, in a shared moment.

“There is a sort of logic in the world we are living in today,” continues Attia. “I really trust that art can bridge something that the left was not able to.”