Art & Exhibitions

Soviet-Era Art Luminary Karlo Kacharava Is Finally Emerging From Obscurity

The Georgian artist is subject of a survey at S.M.A.K. contemporary art museum in Ghent, Belgium.

The Georgian artist is subject of a survey at S.M.A.K. contemporary art museum in Ghent, Belgium.

Kimberly Bradley

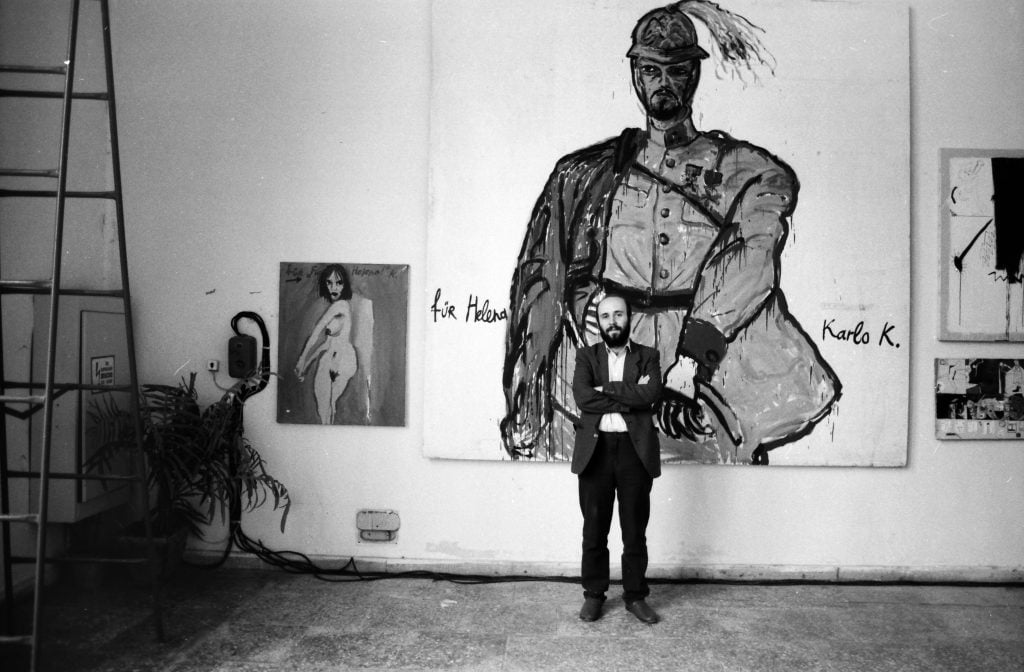

When I first visited Tbilisi, Georgia, in winter 2018, I was taken to meet Lika Kacharava, and in her small apartment we drank local natural wine, ate homemade fare, and viewed many paintings, drawings, and notebooks by her late brother Karlo Kacharava. His art—renderings of brooding people in desolate places, often captioned with aphorisms, poems, and dedications in Georgian and German—hung on nearly every vertical surface, sat stacked up on the floor, or were arranged in bookshelves. His boldly lined and hued work was everywhere, and all of it was powerful. It was astounding.

The apartment remains a time capsule of an incredibly prolific artistic output in a country that, when Kacharava was alive, was asserting its independent identity from the crumbling Soviet Union (the Georgian civil war ran from 1991 to 1993). The artist died of an aneurism at age 30 in 1994, but he’d already feverishly produced thousands of paintings and works on paper.

He was also a cultural critic, poet, editor, educator, and spearhead of two of Georgia’s avant-garde art collectives. The Cold War art-world polymath struck a nerve just as the globe’s tense postwar geopolitical balances were dramatically shifting. Yet, with the exception of a solo gallery show in New York in 1998 and a group exhibition at Metro Pictures in 2017, his work remained largely unknown outside his home country.

A. Döblin (1992). Courtesy of Karlo Kacharava Estate

That is changing. The London-based gallery Modern Art began working with the estate in 2021. This month, the first solo museum exhibition of the artist’s oeuvre outside Georgia opened at S.M.A.K. contemporary art museum in Ghent, Belgium, in part orchestrated by Kacharava’s estate, which is overseen by Lika Kacharava.

The show, titled “Sentimental Traveller,” in a nod to the artist’s desired and actual travels, exhibits 150 of the artist’s works. There are paintings, drawings, sketchbooks, diaries, and ephemera, from photographs and documentary films to album covers and cassettes from the artist’s collection. (I recognized one painting, Mouchette, 1992, from Lika’s wall). The pieces follow the threads of the artist’s production from about 1988 to 1994, in part referring to his sojourns to Spain, Germany, and Russia; most of all, they at last introduce this remarkable body of work to a western European public.

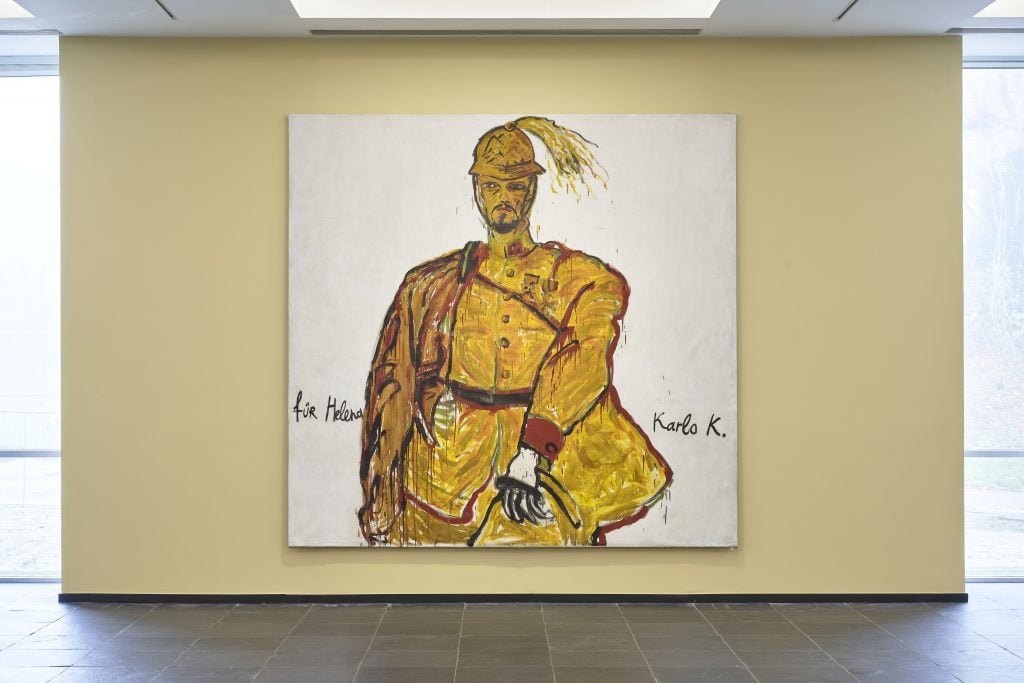

The show opens with a large-scale painting of a bemedaled military general in a yellow uniform—with rough outlines and bold brushstrokes, the figure appears on a blank background as if he’s striding and giving orders. Called General, Für Helena (1988), the piece is dedicated to “Helena” in large letters (Kachavara spent a short time in the Russian military in Siberia; his work was often dedicated to women he knew and loved, but also to inspirational people he didn’t know, like critic Susan Sontag, German filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder, or playwright Bertolt Brecht).

Photo by Dirk Pauwels, Courtesy S.M.A.K.

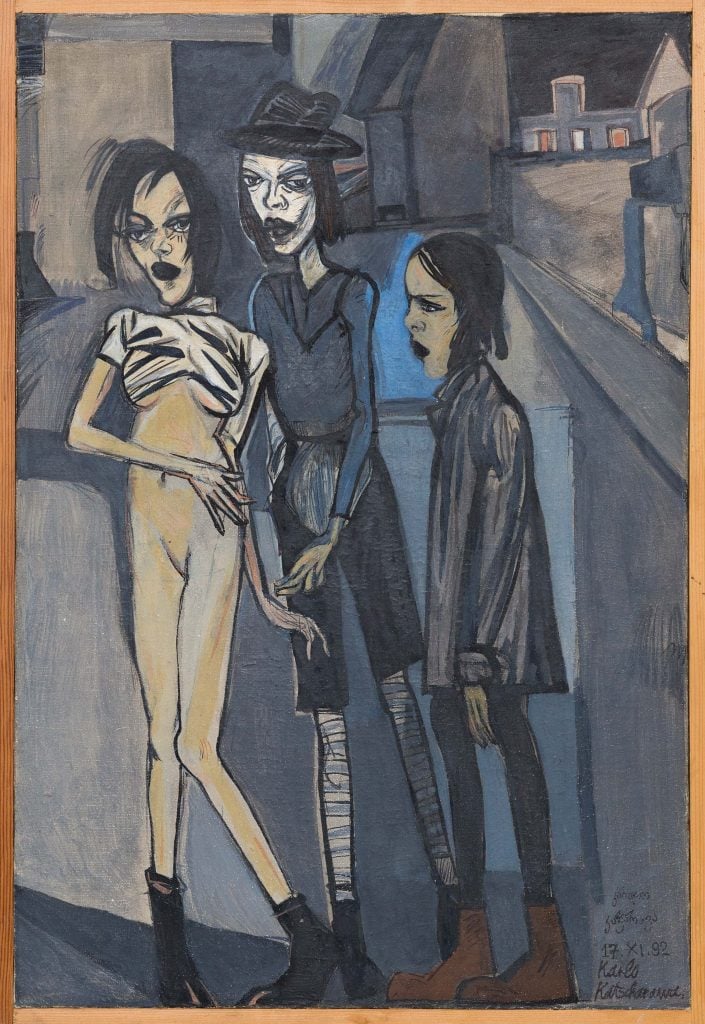

Other works depict universal topics, but also deeply private interactions, that concerned the artist—ideas, books, places, politics, but above all, people—by way of oversize, sharp-featured heads and often distorted bodies painted in blazing colors like cobalt blue, red, and yellow, but at times also in muted grays (that yellow prevails in so many early works, I was told, was because not all pigments were always available in Cold War Georgia). Some works tend toward hyperrealism, while others evoke the stylized figurations of Ernst Ludwig Kirschner, Max Beckmann, or the political critique of George Grosz—German Neo-expressionists who painted street scenes, satirical cartoons, and portraits in the early 20th century.

Cityscapes show structures that resemble Socialist apartment blocks, bleak industrial buildings, like Factory (1988), or a concrete-heavy corner in Milan (Marino Sironi (1992) is a reference to Italian Futurist Mario Sironi). There are portraits of friends, family, lovers. Helena shows up again as a nude, gazing straight back at the viewer; elsewhere, famous figures, like a small-format, solitary portrait of Endy Warhol (1991), exude a certain melancholy.

Anarchist’s Dream (1992). Courtesy the Estate of Karlo Kacharava, Tbilisi, and Modern Art, London

Kachavara often highlighted his era’s power structures: in stark reds and blues, Wir Sind Das Volk (in German, “we are the people,” one of the early slogans of demonstrators against the German Democratic Republic’s government in 1989) shows stern-faced young people seemingly clashing with authorities. And in a series of works on paper labelled “Erased portraits of politicians,” a blacked-out face of Soviet politicians appears on one side of each page, a sketch of a figure or scene on the other. A handful of the artist’s poems appear in Georgian and English on the walls. “This is how Sunday ends in a proletarian ballerina’s sleep” is an especially evocative line, capturing the ennui of late-Soviet-era communism, but also reminding us that the precarity of art and artists transcends time and space.

Kacharava’s works are deeply narrative—some canvasses even function as storyboards, separated into scenes like the grid of cityscapes, abstractions, and portraits in Stars of Cold War (1991). But Kacharava’s narratives are not linear: the sketchbooks and diaries on display seamlessly combine the visual and textual as if he were hyperlinking his thoughts long before digital hyperlinks existed. The show is an excerpt of a vast archive of networked thinking produced in a politically uncertain time, not entirely unlike our current one. After the estate gained notable gallery representation during the pandemic, interest in the work rose further as war broke out in Ukraine: the greater region’s tensions are of course ongoing and Kacharava’s oeuvre is a multilayered glimpse into one part of post-Soviet art history’s earliest chapter.

Irena Popiashvili, a Tbilisi art-world catalyst and the person who’d originally taken me to dine with Lika Kacharava in that jam-packed Tbilisi apartment, told me after the Ghent opening that today’s Georgian art students see Kacharava as an icon, tattooing his words or images on their skin and avidly reading his writings. Older local artists joke that Kacharava is more alive than they are. He was a generation’s bard, guiding Georgian art back to itself, at the same time as forging a way forward for it to enter the outside world. Now, his own work finally has.

Karlo Kacharava “Sentimental Traveller” is on view until April 14, 2024.

More Trending Stories:

Art Critic Jerry Saltz Gets Into an Online Skirmish With A.I. Superstar Refik Anadol

Your Go-To Guide to All the Fairs You Can’t Miss During Miami Art Week 2023

The Old Masters of Comedy: See the Hidden Jokes in 5 Dutch Artworks

David Hockney Lights Up London’s Battersea Power Station With Animated Christmas Trees

On Edge Before Miami Basel, the Art World Is Bracing for ‘the Question’

Thieves Stole More Than $1 Million Worth of Parts From an Anselm Kiefer Sculpture