For years, the See Saw iPhone app has been an indispensable tool for gallery goers in New York and other global art cities, with its clean interface allowing users to scroll through a list of exhibitions on view. One section of the app highlights shows that are opening in the coming week, another highlights which are closing. After selecting from the rich buffet of open shows, the user can watch, with joy, as the See Saw map becomes peppered with flags, each one marking the location of the gallery they want to visit.

But by the end of last week, art fans were looking to See Saw for something else. They wanted to get news on which galleries were still holding their openings this weekend, and which galleries were closing for the foreseeable future.

“We’re obsessed with making sure See Saw is accurate, so we began updating the temporary closure status of individual galleries in response to COVID-19 on the app last Wednesday afternoon with no idea of the ultimate number of closures to come,” said Ellen Swieskowski, See Saw’s co-founder.

A week later, New York’s world-leading constellation of museums and galleries were shuttering due to the coronavirus crisis, and by a need for six feet of social distancing—and a state-wide ban on gatherings over 50 people. Now, See Saw serves less as a way to get from spot to spot than as a reminder of the enormity of what has closed.

A sign is seen in the window of Helly Nahmad Gallery on Madison Avenue on March 13, 2020 in New York City. Photo by Cindy Ord/Getty Images.

“At this point it’s clear that the overwhelming majority of galleries are temporarily shuttered, so we’ve taken a ‘closed until proven open’ approach and updated all galleries on See Saw worldwide with the note ‘Please contact gallery for hours,'” Swieskowski said. “It felt a little eerie having to make that decision, but public health is clearly the number one priority right now.”

And yet, even with the city on lockdown, there’s still a high amount of art that you can see. There’s been a push to develop online viewing rooms, virtual gallery tours, and new ways to circumvent the fact that long-established norms of the art world were shattered in just days. And there’s no reason why you shouldn’t go outside. Asaf Bitton, the health systems innovation leader at Ariadne Labs who wrote a harrowing guide to the desperate need for social distancing that went viral over the weekend, told the New Yorker “the recommendation is to please go outside if you can.” Even if New York gets slapped with an order to shelter-in-place, going outside and taking a walk is listed under “essential activities.”

And if you do go outside, you might be even to see art the old fashion way, in person—through windows, public spaces, or even at the last open gallery in New York.

The Last of the Open Galleries

Archie Rand, Motet #1 (2013), a work in a show at BravinLee, which is, as of now, still open to the public. Photo courtesy of BravinLee.

On Monday, Swieskowski mentioned that two galleries had—for the time being—decided to stay open. The first was Mrs., a small artist-run space in Maspeth, Queens, known for its fiercely loyal locals. It’s also very far away from the rest of the city’s art scene.

“By design, Mrs. is set aside from the fray and somewhat ‘self’ isolated here in Maspeth,” the founders Sara Maria Salamone and Tyler Lafreniere wrote in an Instagram post Friday. “We will avoid shaking hands and will continue to disinfect the gallery.”

Installation view of “Assembly,” a show of work by Damien Davis, Rachel Eulena Williams and Sun You, at Mrs. in Maspeth, Queens.

Likewise, Team, the gallery on Grand Street in Manhattan, had said it would keep the space open for anyone who wants to see its shows by Petra Cortright and Will Sheldon, as two of its staff live in the back of the space. The gallery posted on Instagram that keeping the gallery disinfected would not waste any city resources that need to be directed toward flattening the curve of infections.

But by Wednesday, both had reversed course and closed.

That puts BravinLee, the gallery founded by husband-and-wife duo John Lee and Karin Bravin in 1991, in the unique position of being quite possibly the only publicly operating gallery in New York City.

And it’s not out of a dismissal of the dangers of spreading coronavirus—Lee understands that quite well.

“I’m already and always have been about a seven to eight on the afraid-of-cooties Howie Mandel scale and have always had hand sanitizer in every drawer,” Lee said in an email.

Lee said he sought advice from a doctor who specializes in infectious diseases and he said that, while the situation could change at any time, it would be possible to keep the gallery open and still keep everyone safe. Granted, the situation at BravinLee is quite unique: Lee rides his bike to work—no risk of picking up something on the grimy subway!—and has no employees to infect. His space—which is currently showing works by the artists Archie Rand and Ali Shrago-Spechler—is already isolated on the second floor of a building in Chelsea, and other galleries on his floor vacated long before the crisis hit. He also removed the sign-in book—no touching of pens!—and posted a sign on the door limiting traffic to two to three people at a time, all of whom must stand six feet away from each other.

“I am pained to touch men’s room doors, and I Windex the fuck out of the gallery’s door hardware at least once a day—though the door is now propped open to make the issue moot,” he said.

Lee added that, even while he’s technically open, he only expects friends, family, and die-hard fans of the artists to come by.

Window Shopping

The exterior of Karma, a gallery in the East Village, showing a work by Thaddeus Mosley. Photo courtesy of Karma.

Some galleries never needed people to come inside in the first place—they were built as window spaces, solely to be seen from the outside and never entered. In what now seems like incredible timing, Anton Kern Gallery opened a window-only space in Tribeca in January, on the corner of Walker and Lafayette streets, showing a David Shrigley neon work and a sculptural and video installation by John Bock. In late February, right before Armory Week brought the art world together for what now seems like an extremely ill-advised spree of art fairs and openings, the gallery opened a show of two works by Lothar Hempel that was supposed to be up until March 30, but could be there much longer. Gallery director Brigitte Mulholland noted that, technically, the gallery can stay “open” without breaking any restrictions.

“Maybe Anton was wildly ahead of his time with this concept!” Mulholland said.

Other spaces throughout the city have windows that reveal part of a show, or the entire thing. The East Village gallery Karma has two spaces on East 2nd Street, between Avenues A and B. One is a small space where the entire show can be glimpsed from the street, and the other, while larger, still has a tiny white cube cut into the exterior brick big enough to house one work. It has a Thaddeus Mosley show up, and while you can’t go inside, you can see one gorgeous wooden sculpture while you walk six feet away from everyone else.

Installation view of the Kunle Martins show at 56 Henry. Photo via Instagram.

On the Lower East Side, several galleries with ground-floor real estate have long sported full windows to entice passersby to come inside, stay for a while, get within six feet of another human being, and maybe buy work.

Well, can’t do that anymore!

And given the risks involved in leaving a big window open when no one’s around, Nicelle Beauchene—who shares a two-floor space on Broome Street with veteran dealer Jack Hanley—put down the metal grates, leaving the show by Bruce M. Sherman up inside but visible to no one. Her solution? A bespoke online viewing room, which launched today, that lets her release upon the internet precisely the kind of shows that are behind the metal. First up will be Sherman’s show, followed by a work by John Evans, the late, great East Village collagist who Beauchene just began representing.

“How I can stay engaged and keep supporting my artists?” Beauchene wondered on the phone while driving back to the Hudson Valley (where she lives and has a project space in the summer). She had just photographed more than 80 works by Evans at the gallery for the viewing room.

“Every two weeks we’ll add a new show,” she said. “Its a way to stay relevant.”

Beauchene’s third show will be something appropriately apocalyptic. It’s called “Noah’s Ark” and includes two works by every gallery artist.

Meanwhile, anyone walking through the Two Bridges neighborhood will see all of the Kunle Martins show through the window at 56 Henry—gallery owner Ellie Rines said she’s keeping the lights on. And Rines added that she plans to—safely, while following all precautions—install a new show after Martins’s show come down in late March “so that people can see some art at a distance.”

Going Public

Jean-Marie Appriou, The Horses, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and CLEARING, New York/Brussels; Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zürich/New York. Photo courtesy of Public Art Fund, New York.

Over the weekend, countless indoor arts institutions had closed or delayed exhibitions due to the new health guidelines, including a statewide ban on gatherings of more than 50 people. Even High Line Art, which commissions work that can be seen while walking the popular and very outdoor park on an old train track, had to shut down on Monday amid concerns that people wouldn’t properly social distance on the narrow paths.

The last major institution that remains active might be Public Art Fund. The non-profit currently has two shows open in the public realm in accordance with messaging from city authorities, and they hope that New Yorkers will seek them out if they need to go outside for essential matters—as long as they follow all the necessary precautions. That means—you guessed it!—six feet away, from everyone, at all times.

Even if shelter-in-place is enacted, people are still allowed to leave their homes. “Shelter-in-place, what it does is it formalizes the shutdown of bars and all of that—you should be at home, but you can go out for essential purposes only,” said Daniel Palmer, the Public Art Fund’s curator, who spoke on the phone from his apartment as the offices had, naturally, been closed. “We want to encourage people to go home, but if have they have to go outside, they can see the work.”

He noted that one exhibition, Farah Al Qasimi’s “Back and Forth Disco,” is installed on 100 bus stations across the five boroughs. The stops each show one of the artist’s eye-popping photographs of vibrant micro communities: Yemeni bodegas, barbershops in Bay Ridge, curtain stores in Ridgewood.

“There’s pretty good odds that there is one near your house if you’re taking your dog out,” Palmer said. “Even if you’re not taking the buses, you can still see the sculptures.”

The other Public Art Fund exhibition, a series of large-scale aluminum statues of horses by Jean-Marie Appriou, is installed only at the entrance to Central Park near Grand Army Plaza, but it can have a powerful, maybe cathartic affect of those who live nearby.

“It’s more for people who need to walk their dogs through Central Park, but they are as powerful as ever,” Palmer said. “They’ve become kind of eerie, they’re standing there as sentinels to the park. They’ve always been so surreal—even more so given the surreal moment we’re living.”

The Age of Appointment Only

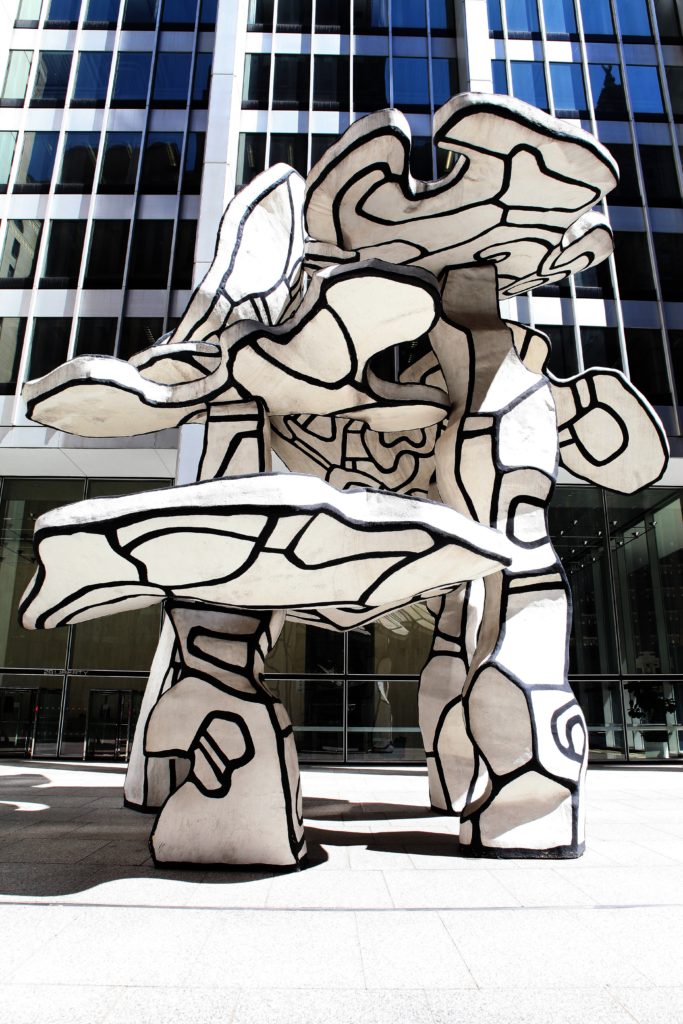

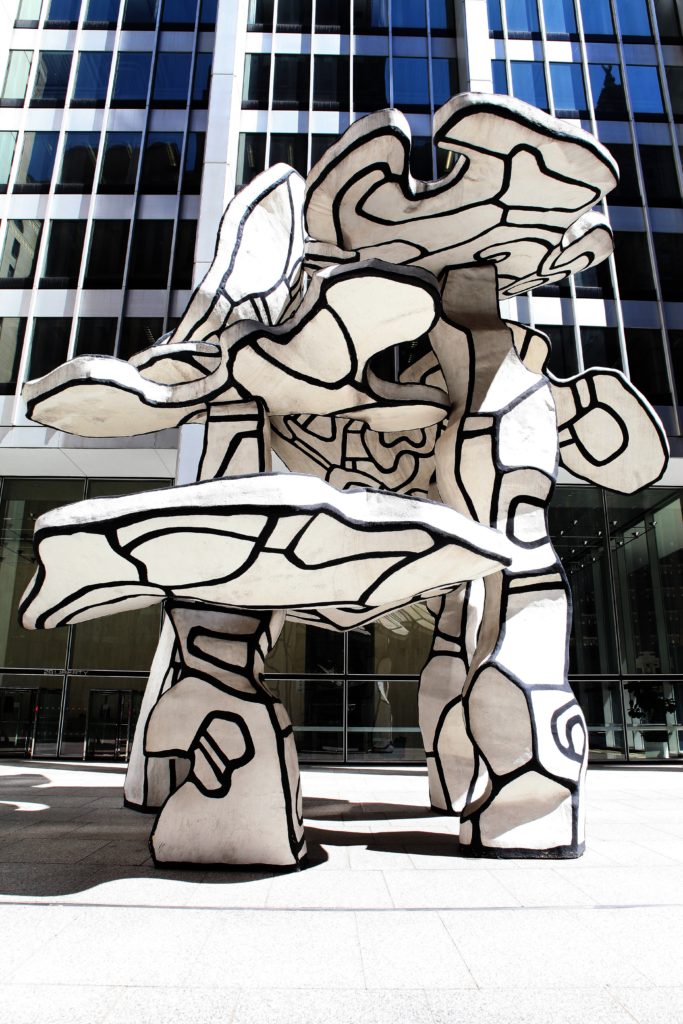

Jean Dubuffet’s Group Of Four Trees sculpture sits in One Chase Manhattan Plaza in New York, New York on April 15, 2016. Photo by Raymond Boyd/Getty Images.

The Public Art Fund does an amazing service of commissioning contemporary artists to make new works for the city, but of course there’s dozens of permanent works of public art that one can savor during these lonely, lonely months to come. There’s the large-scale sculpture by Jean Dubuffet that sits amid the row of midtown citadels, temples of finance titans already reeling from a looming economic meltdown. Someone yearning for the halcyon days of Jeff Koons hysteria can swing by Astor Place and see Balloon Rabbit (Red) in the lobby on 51 Astor. Or perhaps the right work for these hectic times is Joseph Bueys’s 7000 Eichen (7000 Oaks), in which basalt stones are paired with oak trees running down West 22nd Street.

The more inquisitive solo walker can investigate this map—compiled over the course of years by Surface deputy editor Andrew Russeth—which marks hundreds of art-historically important spots in the city: apartments of pioneering collectors once stuffed with masterpieces, storefronts once home to illustrious galleries, the studios where famous artists got their starts, and the sites of epoch-shifting performances.

And there’s one more sign that the art world in New York may not have come to a complete halt during the coronavirus shutdown. By the middle of this week, many of the galleries that were forced to close have become appointment-only, allowing for a single viewer to email and arrange solo visit, with all the social distancing they need accounting for.

And today, See Saw added a “Make an Appointment” button on each gallery listing that lets art-seekers email the gallery with just one touch of a well-sanitized iPhone. Even in a crisis, the app is making a sprawling gallery circuit accessible.