Market

What Actually Works When It Comes to Selling Art Online? Successful Early Adopters Share 5 of Their Business Secrets

Among the major lessons is that transparency benefits everyone.

Among the major lessons is that transparency benefits everyone.

Tim Schneider

When we rang in the new year just over three months ago, thousands of participants in the global art industry thought they would be spending the week of March 16 in Hong Kong, ping-ponging between Art Basel’s latest edition in the city and a slew of gallery openings, institutional programs, and networking events.

Instead, much of this same population is now hunkered down inside their homes in an expanding global lockdown that has all but shuttered the art world along with the world at large.

This unprecedented crisis has finally forced every dealer and artist to turn toward the digital horizon. Most notably, Art Basel moved up—and scaled up—the long-planned launch of its first online viewing rooms to the same dates as its cancelled Hong Kong fair, in an attempt to replace the opportunities its exhibitors and collectors lost. Several respected dealers, including Los Angeles’s Susanne Vielmetter and New York’s Di Donna Galleries, also announced the imminent debut of their own in-house online viewing rooms in the preceding days. Put it all together, and the market is now in the midst of a massive new commitment to the virtual experience.

But while necessity is often the mother of invention, panic is often the father of hasty mistakes. Thankfully, the art market does harbor a small group of early adopters who have already been embedded online for years. And although there are no magical solutions for galleries exploring e-commerce, some important—and often counterintuitive—themes emerged from discussions with some of these veterans of virtual space.

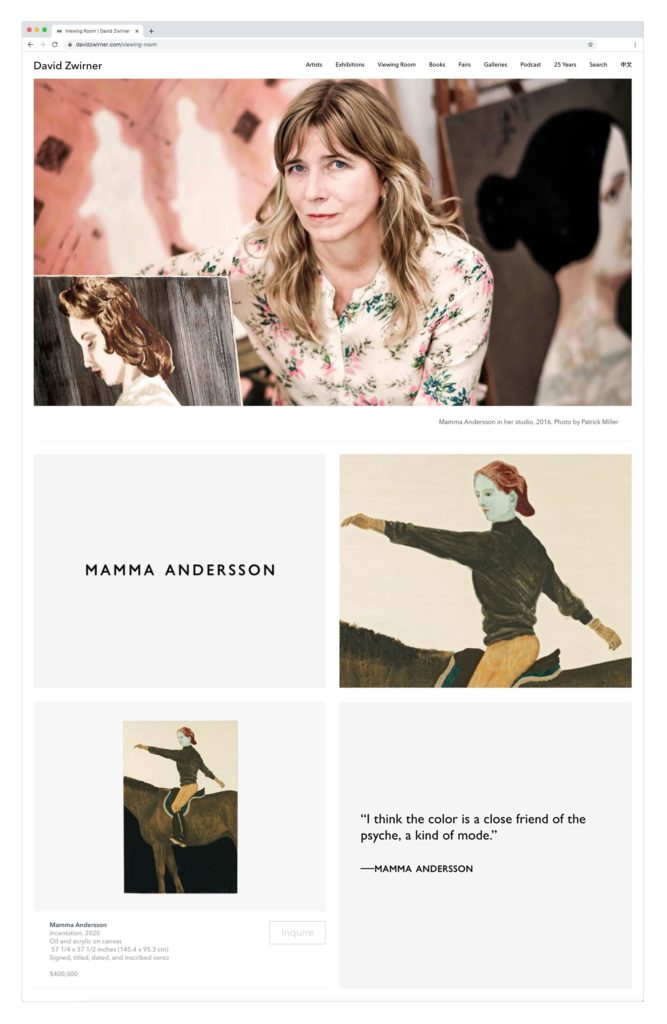

David Zwirner Online’s “On Painting: Art Basel Online,” March 20–25, 2020. Courtesy David Zwirner.

Six years after the publication of the first articles about selling art through Instagram, some common expectations have coalesced around art-market e-commerce: for instance, that the best works to offer are vibrant, poppy paintings, drawings, and photos; and that the artists who sell well are either stars with brand equity, or emerging talent at approachable price points.

Well, throw those expectations out the window, according to experts.

“I wouldn’t limit a certain price point or medium to online platforms,” advises Elena Soboleva, who in 2018 joined David Zwirner as the gallery’s first digital director after working to organize shows independently and as lead curator and specialist at Artsy Projects.

Although Zwirner has offered works priced as low as $1,000 in past online viewing rooms (which it has been consistently programming since January 2017), the gallery says it sold a $2.6 million work by the long-renowned Marlene Dumas on the first preview day of its new virtual exhibition, “On Painting: Art Basel.” Soboleva also says that, contrary to popular belief, the gallery has also had “lots of success with large sculpture,” arguably the polar opposite of what is supposed to sell well online.

Nor are online buyers predominantly young and internet-savvy upstarts, says Pace Gallery president and CEO Marc Glimcher. After launching in-house online viewing rooms for private clients in 2019, the gallery made them public amid lockdown. What draws digital consumers “isn’t a personality type, or some kind of Generation Z [and] millennial phenomenon,” he says.

Soboleva says that 40 percent of sales inquiries that come through Zwirner’s in-house online viewing rooms are from new clients, but that visitors and buyers span regions, lifestyles, and professions. Longtime collectors, museum trustees, and even other artists are all active, she says.

This isn’t just outlier data from mega-galleries. Julia Dippelhofer and Michael Nevin, who run The Journal Gallery in Tribeca, have also, since 2017, had an online sales complement titled Tennis Elbow. Although Dippelhofer and Nevin are reassessing how exactly to proceed in the social-distancing era, the gallery has traditionally shown one-week-only exhibitions in its physical space while Tennis Elbow has offered concurrent one-week-only online presentations of available works by the same artists.

While Dippelhofer says she and Nevin knew they would use Tennis Elbow to feature some “work that would appeal to newer collectors in a lower price range,” they have also benefited from mixing in “work by established artists that won’t be in that same price range.” The attraction in that latter case, you ask? That leads us to our next tip…

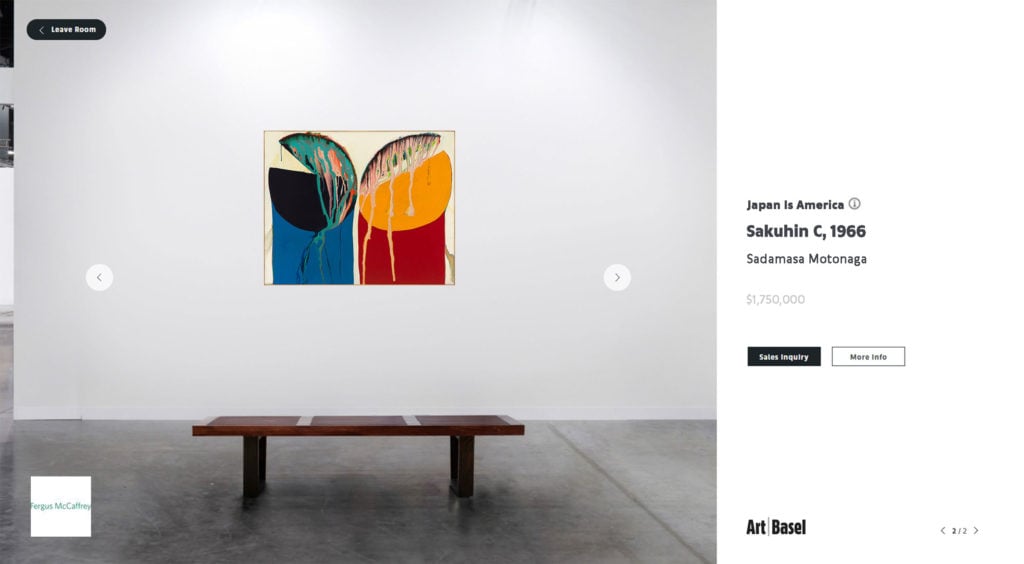

Art Basel’s March 2020 Online Viewing Room, featuring a work from exhibitor Fergus McCAffrey’s exhibition “Japan Is America.” Courtesy of Art Basel.

One key part of Tennis Elbow’s longevity and what Dippelhofer calls its “more democratic approach” has been its membership program. To join, applicants are merely asked to supply a few basic details (name, email, phone number) and a written summary of who they are and what they collect. Members also accept terms that include a promise not to resell work within two years of acquisition and grant The Journal right of first refusal thereafter.

Once accepted, members get to access new Tennis Elbow offerings a full day before non-members. They are also “pre-approved” to acquire what they find on the platform. The process means that higher-priced, more in-demand works by established artists are more accessible to members than they might otherwise be. And the concept is resonating. Membership now numbers in the hundreds and has roughly doubled since The Journal added the Tennis Elbow membership program in May 2019.

Similar transparency is at work in Art Basel’s nascent online viewing rooms. Although the virtual fair will open to the public on Friday, March 20, visitors to its two preceding VIP days gain access by logging in with their Art Basel credentials. These credentials correspond to limited but useful data about each user’s history, such as which events they’ve been invited to and whether they are members of Art Basel’s Global Patrons Council. This information is transmitted to dealers automatically when a VIP inquires about an artwork, acting as “a kind of verified lead” for galleries working with clients for the first time, says Art Basel global director Marc Spiegler.

Transparency extends to the pricing side, too. “Although historically there’s been some hesitancy to show prices in a fair environment, we wanted to create the conditions for success,” Spiegler says. In consultation with the more than 30 galleries comprising the selection committees for its three fairs, Art Basel’s leadership “evaluated extensive research that artworks with price data are exponentially more likely to be sold.” The result? Every piece in Art Basel’s online viewing rooms includes either an exact price or a fair-approved price range, from under $10,000, to over $1 million, with six increments in between.

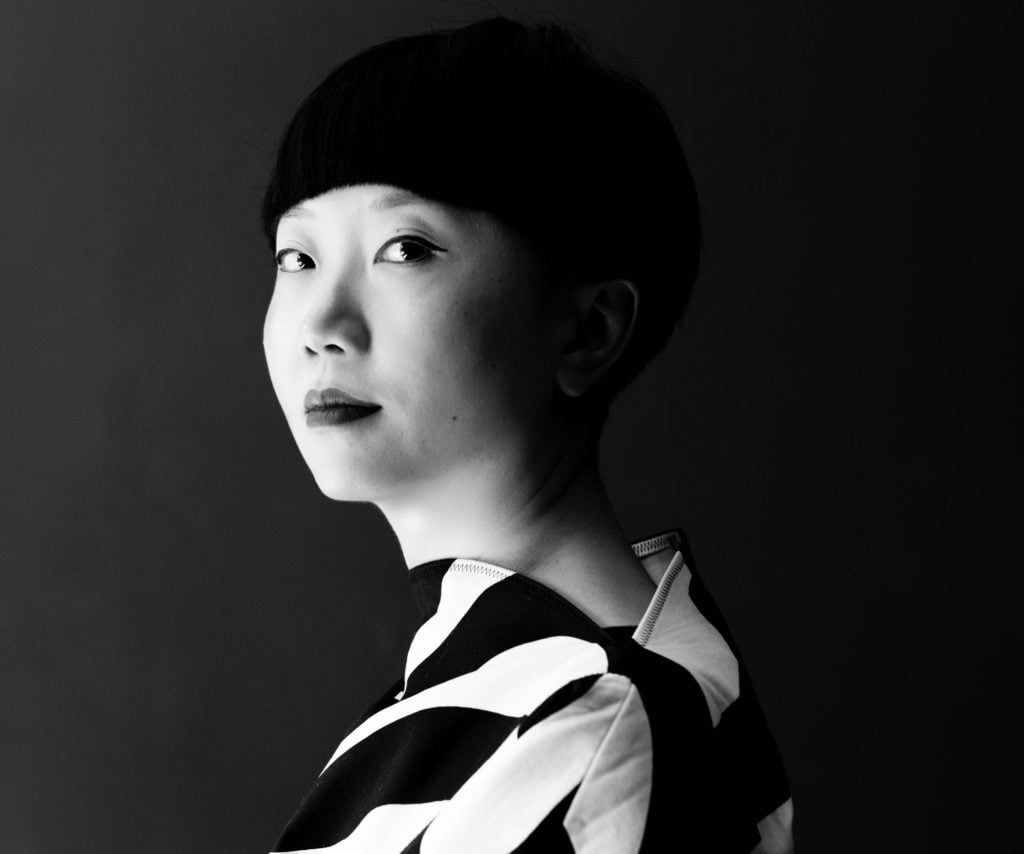

JiaJia Fei, 2019. Photo: Michael Avedon.

But when asked about some of the misconceptions revolving around making art experiences available online, JiaJia Fei was quick to point to “the fallacy of, ‘If you build it, they will come.’”

In January, Fei launched the art industry’s first digital-media agency after spending four years running the Jewish Museum’s online presence as its director of digital, as well as the previous six years building the Guggenheim’s digital-marketing department. Her warning: launching an online viewing room does not automatically guarantee you’ll find an audience.

“The most successful digital initiatives now are people activating their collections and artworks through social media, as opposed to a very difficult-to-build custom solution,” she says. “It’s about more than building a space. It’s about building the conversation around it.”

What the art world needs to do most, in her experience, is engage its audience. Social media provides an efficient, effective, and no-cost technology to forge or strengthen the connections that can translate into visitorship, sales, and other tangible benefits. That’s why she stresses that “analog outreach” remains hugely important to any digital effort; the clients most likely to buy remotely are still the ones that dealers already know well.

Joe Kennedy, cofounder of the contemporary gallery Unit London, agrees. Since opening a pop-up space in Chiswick in 2013, Kennedy has used social media and digital content to construct what he calls “our own community” outside the traditional art-world infrastructure. The strategy propelled the gallery into a 6,000 square-foot space in Mayfair in 2018 and Kennedy onto the Serpentine Gallery’s Future Contemporaries Committee—all without Unit ever exhibiting at an art fair.

“Art is not about viewing a piece in an empty room and wanting to buy. It’s about having a social experience, discussion, seeing who else is participating,” says Kennedy. “You get that with social media. You can’t really translate it into a virtual walkthrough.”

This is why Unit does not operate an online viewing room. However, it does employ a dedicated four-person content team. Although, like nearly every other art space in the Western world, the gallery has temporarily closed its physical location, Kennedy says Unit will channel much of the budget for its suspended exhibitions into precisely targeted digital and social-media ads, as well as robust content. His team will also be using its off time to get in touch with clients the old-fashioned way: by picking up the phone and calling.

The Journal Gallery’s new space in Tribeca

It would be self-destructive for a modest gallery to try to mimic a mega-gallery’s analog strategy, and the same is true for any digital strategy.

“As a larger gallery, we have a brand and an audience that come to us,” Soboleva, the Zwirner dealer, says. “But I’d argue there are a lot of younger galleries that can be quite creative and nimble online. They just won’t use the same format.”

This advice is especially relevant while day-to-day life is being bent into its current surreal state. “Everyone’s feeling that panic across every economic sector,” Fei says. But “it takes months or years to set up something online as sophisticated as some of the larger galleries.”

So while galleries need to forge into cyberspace for survival’s sake, they also need to think about what’s achievable—which doesn’t necessarily mean abandoning ambition. Dippelhofer and Nevin are now working to create an editorial element around Tennis Elbow and its Instagram presence. They are considering content such as Q & A’s with their artists about how they’re dealing with the professional and personal fallout of the global health situation. Fei also highlights that almost any creative gallery can quickly and affordably add value with existing DIY tools, such as Squarespace to build websites or online stores, and Zoom to transform in-person talks or panel discussions into videoconferences accessible anywhere.

Supporting a larger mission can also strengthen a gallery’s online presence. To that end, 10 percent of The Journal’s commission on every Tennis Elbow purchase during the lockdown era will be donated to Food Bank for New York City, Citymeals on Wheels, or No Kid Hungry on a rotating basis.

Of course, online storytelling and editorial content can be scaled up dramatically if resources allow. Gagosian’s March 2019 online viewing room for Albert Oehlen’s Untitled (1988) included video interviews between COO Andrew Fabricant and director Sam Orlofsky, as well as charts on the artist’s market trajectory. Zwirner’s recent online viewing room for James Welling’s super-saturated photographs juxtaposed reference images and historical background alongside available works in an attempt to create “an educational and cultural experience,” Soboleva says—just like a traditional exhibition.

The possibilities are infinite, but each decision communicates something about the gallery and impacts the works’ reception. So choose wisely.

Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai at Google’s Developers Conference in 2018. Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images.

Part of what restrains innovation is also what makes us vulnerable to new crises: insufficient effort combined with insufficient imagination. Among professionals tasked with managing risk in all spheres, there is a maxim that people tend to prepare for the disaster that already happened, not the one that may come next. The past is concrete and easy to understand; the future is abstract and difficult to imagine.

Similarly, flawed technology tends to address the world as it is now, not the one we might be hurtling toward. Online veterans of the art industry suggest that dealers moving aggressively into the digital world would do well to keep this in mind.

Kennedy says this is part of the reason Unit London’s cyber-first strategy has worked so well: because social and digital media have been the program’s bedrock since 2013. “Everything is viewed through that prism. It’s not a bolt-on at the end,” he says.

Galleries that have not seriously invested in social or virtual resources until recently, however, risk skipping important steps for expediency’s sake—and failing to align themselves with what’s ahead.

“There is no finite endgame in tech products,” Fei says. “The minute you release something, you have to be thinking about version 2.0.”

So just as many galleries ignored the early stages of e-commerce in years past, they now risk missing an even larger industry shift—one that has been a decade in the making—if they merely focus on playing catch-up. In this moment of flux, then, the question is which galleries will manage to address their current challenges while continuing to relentlessly evolve for the brave new world to come.