People

Lorraine O’Grady, Conceptual Artist and Critic, Dies at 90

O'Grady's profile had grown significantly over the last 10 years.

O'Grady's profile had grown significantly over the last 10 years.

Adam Schrader

Lorraine O’Grady, who went from an early career as a research economist for the government to a second life as a conceptual artist and cultural critic in her mid-40s, died Friday. She was 90 years old. She is best remembered for her diptychs which juxtapose images for a critical look at gender, race, and class disparities, and as a rock music critic for Rolling Stone and the Village Voice.

O’Grady’s death was confirmed by Mariane Ibrahim, the art dealer who represented her and has venues in Chicago, Paris, and Mexico City. Ibrahim did not reveal her cause of death.

“Lorraine O’Grady was a force to be reckoned with,” said Ibrahim. “Lorraine refused to be labeled or limited, embracing the multiplicity of history that reflected her identity and life’s journey. Lorraine paved a path for artists and women artists of color, to forge critical and confident pathways between art and forms of writing.”

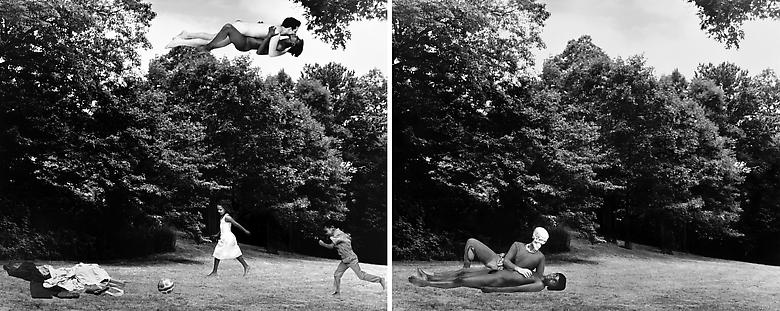

Lorraine O’Grady, The Clearing (1993). Courtesy alexandergray.com.

O’Grady was born in Boston in 1934 to West Indian immigrants and was educated as a child at the elite Girls’ Latin School. She went on to study economics and Spanish literature at Massachusetts’s Wellesley College. After graduating in 1955, O’Grady worked for more than five years as a research economist for the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“I think the Department of Labor knew before I did that I wasn’t cut out for government service!” O’Grady once wrote of her early career. “Still, though it was the most welcoming to women, even at Labor there were limits. You could look around and see that division chief was as high as any woman would get.”

Lorraine O’Grady, Untitled (Mlle Bourgoise Noire asks, “Won’t you help me lighten my heavy bouquet?” (1980-83/2009). © Lorraine O’Grady/Artists Rights Society (ARS) NY. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York.

She left that job in 1961 and sent her son to live with his father, who was living with his parents, believing they could provide the child “a more stable home.”

O’Grady attempted a fiction writing career for years, even participating in the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 1965, before finding part-time work in 1968 as a multi-language translator at a small Chicago firm that had a contract with Playboy magazine. She also worked part-time for Jesse Jackson’s Operation Breadbasket, which pressed white-owned business to hire African Americans and to purchase goods and services from Black-owned firms.

When the owner of the translation firm died, O’Grady took over, dropped all clients but Playboy and picked up Encyclopedia Brittanica. She soon moved to New York, where she found success through the 1970s as a critic for Rolling Stone and the Village Voice, and taught literature at the School of Visual Arts as she picked up her visual arts practice.

Lorraine O’Grady, Art Is (Troupe Front), 1983/2009. © 2018 Lorraine O’Grady/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York.

While her art practice did well in the decades since finding her path into the art world, O’Grady really began to thrive in the last 10 years of her life, as publications such as New York proclaimed: “More than four decades into her trailblazing career, Lorraine O’Grady finally has the world’s attention.”

O’Grady has been the subject of numerous one-person exhibitions. Her 2021 retrospective ”Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And” at New York’s Brooklyn Museum, traveled to the Weatherspoon Art Museum in North Carolina and to the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, where it was on view earlier this year. At least six of her works are in the current exhibition, “Flight into Egypt: Black Artists and Ancient Egypt, 1876–Now,” at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“People tell me my world looks as if it could have been made yesterday,” O’Grady once said. “To me, this is a sign that little has fundamentally changed. Even our successes stay safely bracketed. My tasks in art remain the same: to find ways to develop and maintain a rich inner life while standing firm in the attempt to overturn the depredations of the outer world.”