People

‘It’s Time the Old Rulebook Was Rewritten’: Artist Marianna Simnett on the Virtues of Shocking Imagery and Difficult Art

Simnett says artists need to stick to their guns and insist on radicality.

Simnett says artists need to stick to their guns and insist on radicality.

Kate Brown

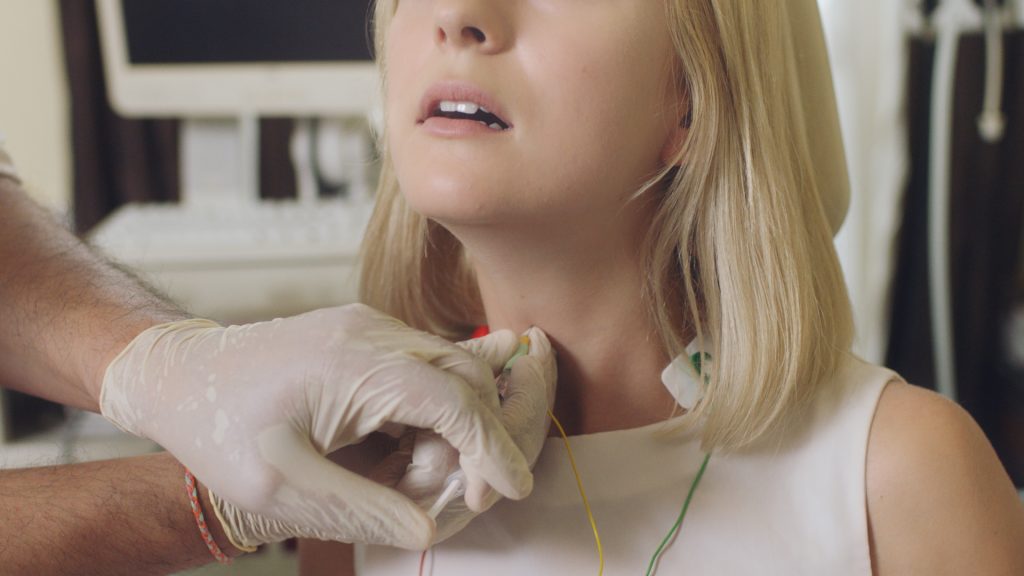

Five years ago, Marianna Simnett was sitting in a doctor’s office with a syringe an inch away from her throat. A surgeon was about to insert a dose of Botox into her neck to lower her voice—a painful procedure, she told me in her Berlin studio last month, that would affect her speech for about three months as part of an artwork titled The Needle and the Larynx (2016).

“I was prepared for permanent surgery, but, thankfully, the surgeon came up with a temporary solution,” she told me.

In an art world that often cordons off offensive subject matter, Simnett’s work—which has involved masochism, surgeries to orifices, narratives of child murder, animal death, and reanimated roadkill—is a bit dangerous. And for that reason, it can strike themes that are deeply human.

Marianna Simnett, The Needle and the Larynx (2016). Courtesy the artist and Serpentine Galleries, London.

The artist, who works without a gallery by choice, has created a hybrid model to keep her studio operational: her web shop, which she launched to get through the pandemic, floated her while she opened a solo show at the Institute of Modern Art in Brisbane. This year, she will be a part of group shows at the Kunstverein in Bonn, the Julia Stoschek Collection in Berlin, and the British Art Show 9, as well as a commission for Castello di Rivoli in Turin.

Just as her work does not provide easy-watching, it is not exactly easy to define it, either. She plays the flute and paints delicate water-colors of creatures. She sings. She writes, scores, shoots, and edits her surrealistic films, among other creative undertakings.

Simnett moved to Berlin in October after a period of nomadism between a handful of places that included London, rural England, and Australia. Despite her reluctance to pin down a home, it’s been a surprisingly positive experience. She quickly found a studio and learnt German which, she says, gets her through the German bureaucracy—and anyway, she is happy not to live in a metropolis like London. It’s a “sinkhole,” she said. “We need to stop seeing these monopolizing cities as a paradise or something to aspire to.”

Marianna SimnettBlood In My Milk(2018). Exhibition at New Museum. Photo: Maris Hutchinson. EPW Studio.

Simnett is loathe to refer to her nationality by her British passport, especially given that she is half Croatian. In Tito’s Dog, a video made last year during lockdown, Simnett moves back and forth between Croatian and English while applying heavy makeup to make her look like a dog; it seems harder and harder to breathe beneath the cosmetics as she speaks from the viewpoint of former Yugoslavian president Josip Broz Tito’s canine pet. She tells the story of how the dog leapt to save his master, taking the fatal shrapnel from a bomb. An attempt to dissolve borders is at the core of her work. Now, living in Berlin, she told me she could begin to incorporate German culture into her practice.

“I want to dismantle this idea of Western European centrism, that English is the given spoken language.” she said. “I want to accept and promote more vulnerable ways of speaking and being understood.”

Marianna Simnett’s The Bird Game (2019). Courtesy the artist, FVU, the Rothschild Foundation and the Frans Hals Museum.

Perhaps that sensibility comes from an upbringing on peripheries. Simnett grew up on London’s outskirts, on a houseboat that belonged to her transient father. “My neighbors were clowns, drunks, and pianists,” she said of her childhood home. “Everyone had chosen to be an outsider.”

Her mother immigrated to the UK from former Yugoslavia, which suffered a violent breakup through the 1990s and into the 2000s. “My family story on that side is riddled with war,” she said. Her family’s attempt to escape Europe through France at the onset of the Second World War resulted in capture. Their wealth was liquidated and most of them were murdered, but her Jewish-Croatian grandfather survived after he fainted while being shot at by a firing squad, waking up to find the other prisoner dead. He bit his arm to check that he was still alive, Simnett said.

Marianna Simnett Faint with Light (2016). Installation view at Copenhagen Contemporary, Copenhagen, 2019. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Anders Sune Berg.

The artist interpreted his survival story with Faint With Light, an installation that will be on view at Julia Stoschek in February as part of “A Fire in My Belly,” a group show focused on acts of violence. In the work, strobe lights pulsate rhythmically while audio plays—viewers can hear Simnett hyperventilating before her head hits the ground.

“My family doesn’t dwell on death and violence, not as much as I do. They say it in a whisper. They describe it like a shopping list. My grandfather wasn’t always very nice, but he didn’t have nice things done to him. It’s hard to love if nobody ever teaches you how to love.”

She wonders if her recurring themes of abuse are not a result of generational trauma, given that she was born into a world of privilege by comparison. “And yet there is something tugging on me,” she said. “There is an insistence and a residue that forces me to do what I do.”

Marianna Simnett, Covering (sure thing), (2020). Courtesy the artist.

In her 2020 video work Pillow, a striking and tender stop-motion animation film Simnett, an interspecies group of roadkill meet for an ceremonious orgy. A gentle folk song plays as their gaping mouths are re-framed as expressions of love and pleasure, not pain caused by human interference.

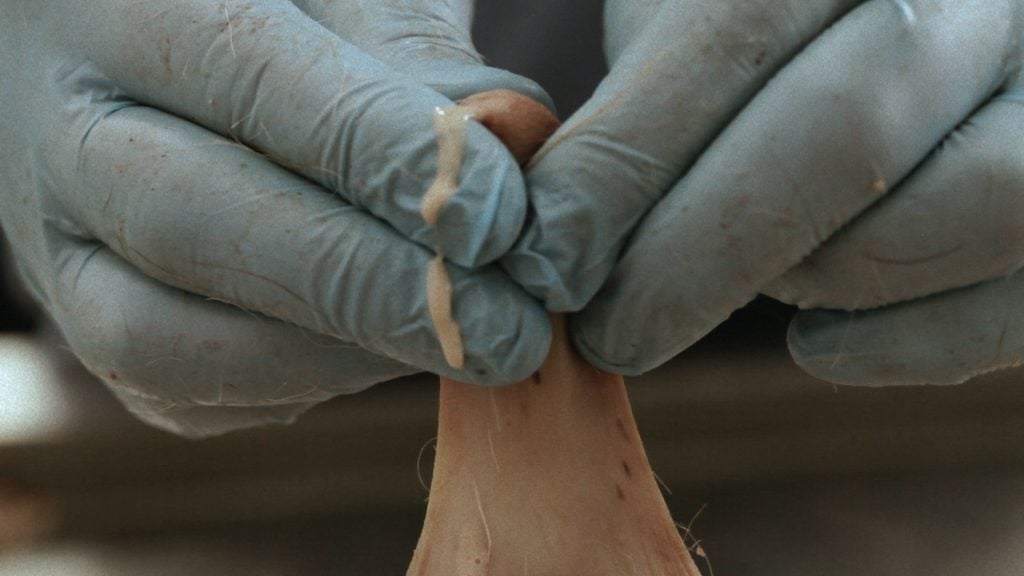

Simnett finds the work romantic, and she has a great deal of empathy for animals, which appear throughout her work. In The Udder from 2014, the mammary gland of a cow undergoes an operation in a comment on bio-capitalism—the extraction of resources from humans and animals is a recurring topic.

“I don’t want art to just decorate… Yet the aim has never been to shock,” she told me. “I want to create an internal shift in someone. More than the gore, what is more frightening about my work are the leaps between logic.”

Marianna Simnett The Bird Game (film still, 2019). Courtesy the artist, FVU, the Rothschild Foundation and the Frans Hals Museum.

Constructing these skips through logic means she can craft surrealistic narratives. Scenes of implied child abuse and murder occur in The Bird Game (2019), where a malevolent crow picks kids off, one by one. That work, Simnett said, was canceled by various institutions.

“People have been offended by my recent work,” she said. “What’s funny to me is that the more violent works are those involving self-exploitation or self-abuse—the audience seems to accept that. I thought fiction was supposed to be a safe space to explore things you shouldn’t be doing in real life. I’m physically endangering myself less now, but ironically, the work is being censored more.”

One problem, she told me, is a rising tide of accelerated clashing between leftist artists and conservative patrons, a warped relationship that has seeped into art discourses. “It’s a dominating structure of the art world and its market. We want radical art, but we also want to make sure patrons pay for it. Artists need to stick to their guns and not be led by institutional frameworks and box-ticking.”

“Shocking art is much more digestible after a few generations,” she added. “No one likes it at the time. Hermann Nitsch and the Viennese Actionists have become aestheticized.” There are boundaries, of course. And shock for its own sake does not interest her.

The Udder (2014). Courtesy the artist

That environment is one reason she prefers not to work with a gallery.

“I never fit into a traditional gallery model so I have invented an alternative. I sell my major works to collectors directly,” she said. “But I also offer smaller works and editions at very affordable prices in my shop.”

Works on her online shop—including silk throw pillows with a printed still from Pillow of the protagonist squirrel—are all priced at €200 or under. “I don’t give 50 percent to a dealer, so I can keep it affordable.” While she is open to partnering with someone eventually, the situation would need to fit her multi-stranded way of working, something other than the current traditional model of dealer-artist relationships.

“I’d rather take a leap of faith with someone who wants to create a new form of representation We can no longer separate art from other fields. I want to work fluidly between all disciplines.” she said. “It’s time the old rulebook was shattered and rewritten.”