Books

‘Van Gogh’s Life Was Made for a Novelist’: Author Martin Bailey on the Artist’s Mysterious Last Days—and How He Really Died

Bailey is the author of the new book 'Van Gogh's Finale: Auvers and the Artist's Rise to Fame.'

Bailey is the author of the new book 'Van Gogh's Finale: Auvers and the Artist's Rise to Fame.'

Sarah Cascone

Many of us know the story about the end of Vincent Van Gogh’s life, and how a mysterious madness ultimately caused him to shoot himself. But is that really the full truth?

In his new book, Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers and the Artist’s Rise to Fame, art journalist Martin Bailey paints a more complete picture of Van Gogh’s final days, revealing them to be a remarkably fruitful, prolific period that led to the creation of 70 paintings in as many days.

“It’s certainly his most productive period,” Bailey told Artnet News. “Van Gogh worked very fast, so when he was in reasonable health he did produce a lot of works, but not at the rate of a painting a day—and he was also doing drawings, probably a similar number as well. He led a very busy life the last 70 days.”

Bailey knew the numbers going in, of course, but their true magnitude only became clear over the course of writing the book.

Vincent van Gogh, Portrait of Adeline Ravoux (1890).

“When one actually looks at the paintings in detail you realize what an achievement it was,” Bailey said. “He’d done so many important works, day after day—of course that makes even more tragic that his life came to an end.”

The volume marks the end of a series of books documenting Van Gogh’s time in France, which Bailey has been working on for the past decade. Van Gogh’s Finale follows The Sunflowers are Mine: The Story of Van Gogh’s Masterpiece (2013), Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence (2016), and Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum (2018).

“Van Gogh achieved so much in 10 years,” Bailey said. “It was such a short period, but he achieved much more than most artists have in a lifetime. In a way, I’m thankful for what he did produce, rather than thinking too much about what might have happened if he lived longer.”

We talked to Bailey about what people might be surprised to learn about Van Gogh’s last days, about charting the artist’s posthumous rise to global fame, and why—despite what recent movies might lead you to believe—Bailey still believes that the Dutchman died by suicide.

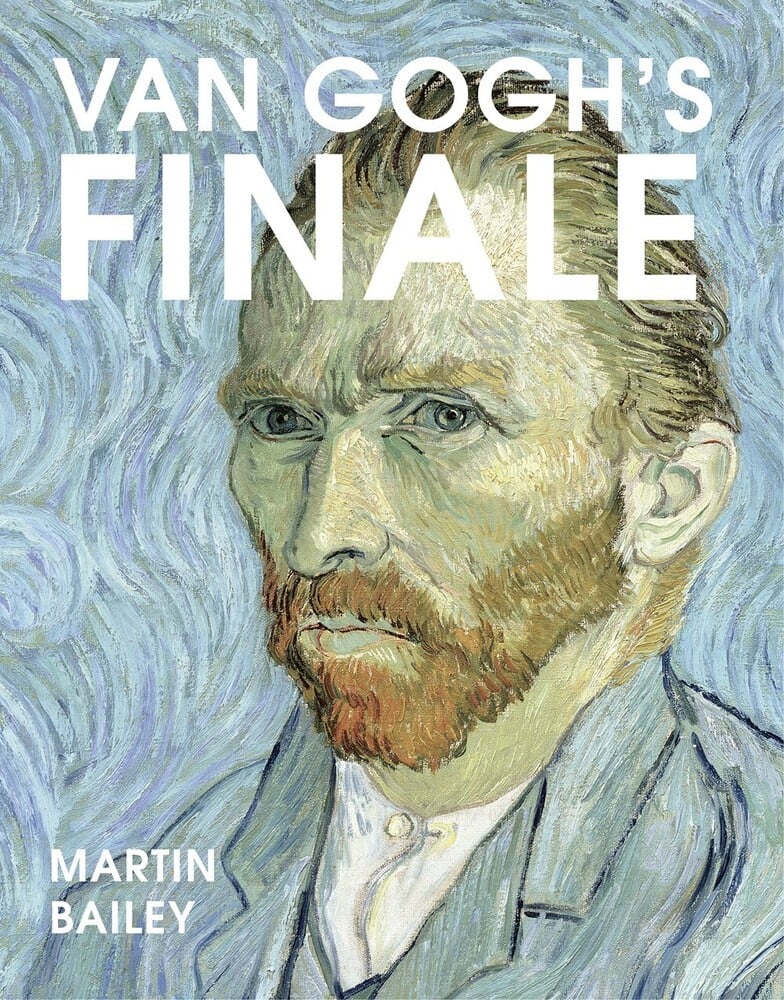

Vincent van Gogh, Marguerite Gachet in the Garden (1890). Collection of the Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Why do you think Van Gogh painted so many works during these final days? Was it perhaps an unconscious anticipation of his death?

Van Gogh kept having recurring crises, and I think he was aware that he was not going to live to old age. In that sense, he wanted to get as much done as he could. But I don’t think he realized when he arrived in Auvers that the end was any more imminent than it had been earlier.

He was always very keen to produce as much as he could. When Van Gogh had been at the asylum the year or so before he moved to Auvers, he was ill for nearly half the time, so his productivity was halved.

I think the reason why Van Gogh was so productive was that he had a great ambition and desire to paint. That was really the only reason he was living.

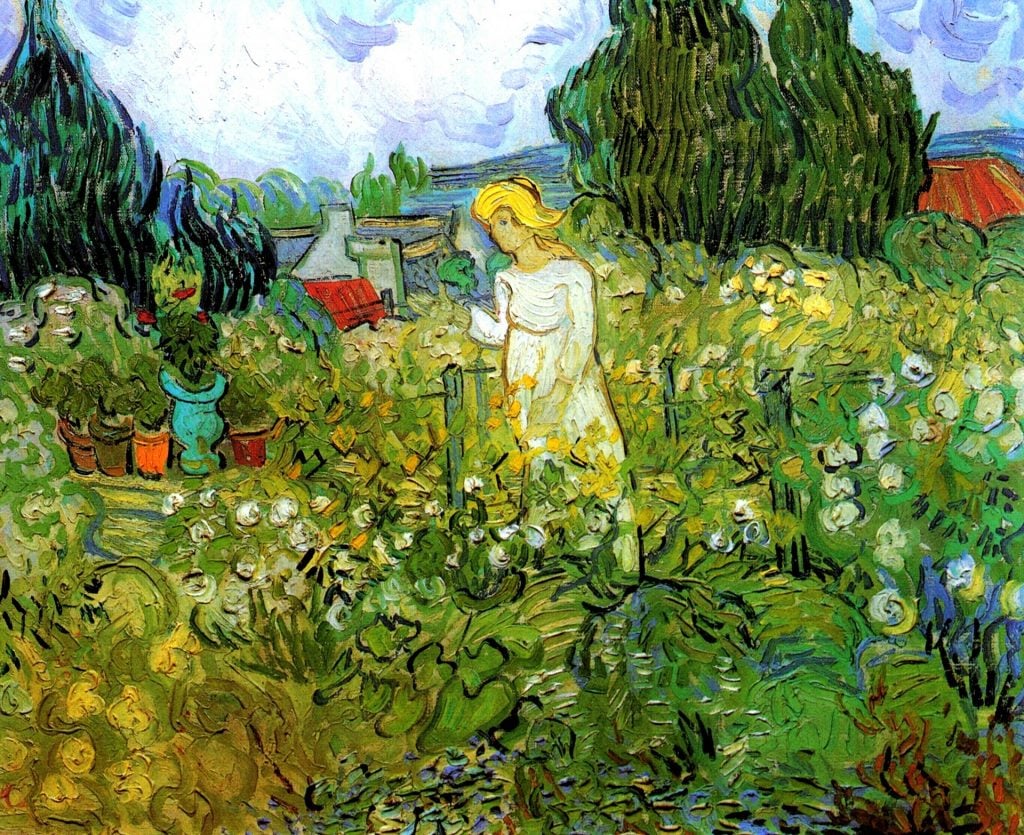

Vincent van Gogh, Portrait of Dr. Gachet (1890).

What do you think are the greatest Van Gogh masterpieces from Auvers, and why do you think he did such fine work there?

The Portrait of Dr. Gachet is a marvelous portrait, particularly the first version. It is very interesting because of the close relationship that developed between Van Gogh and Gachet, who started off as his doctor and then became a friend. He played a key role in Vincent’s stay, and I think readers will be surprised to learn a bit more about this extraordinary person.

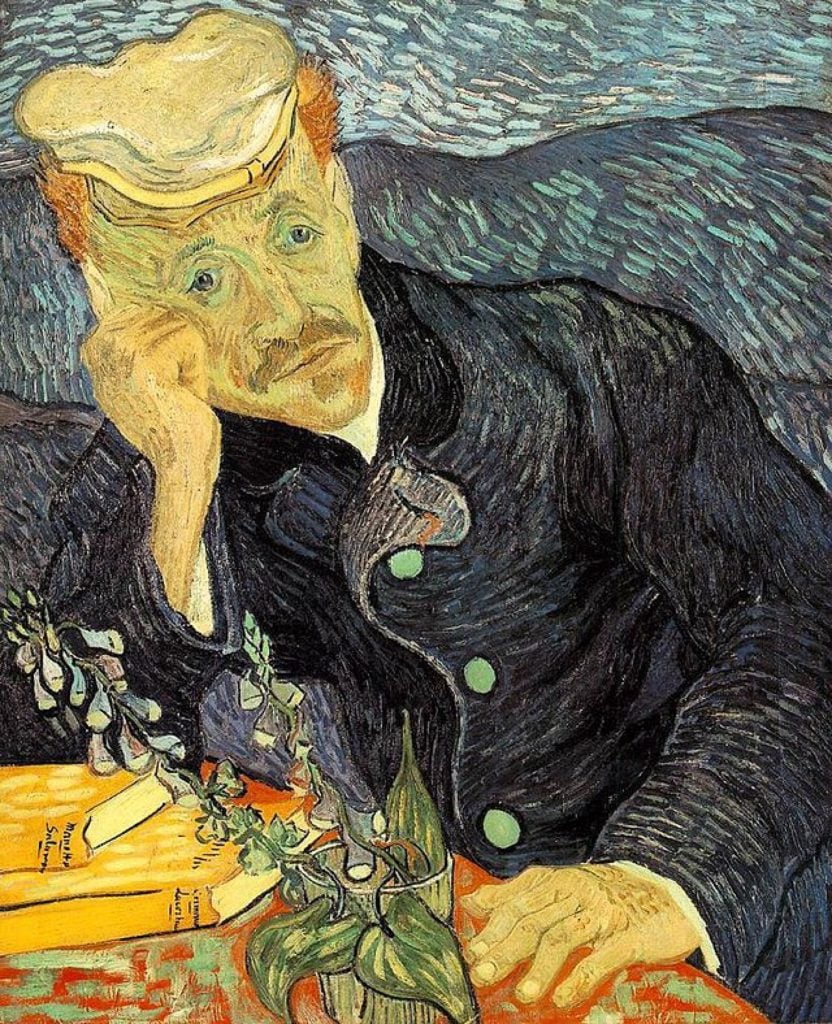

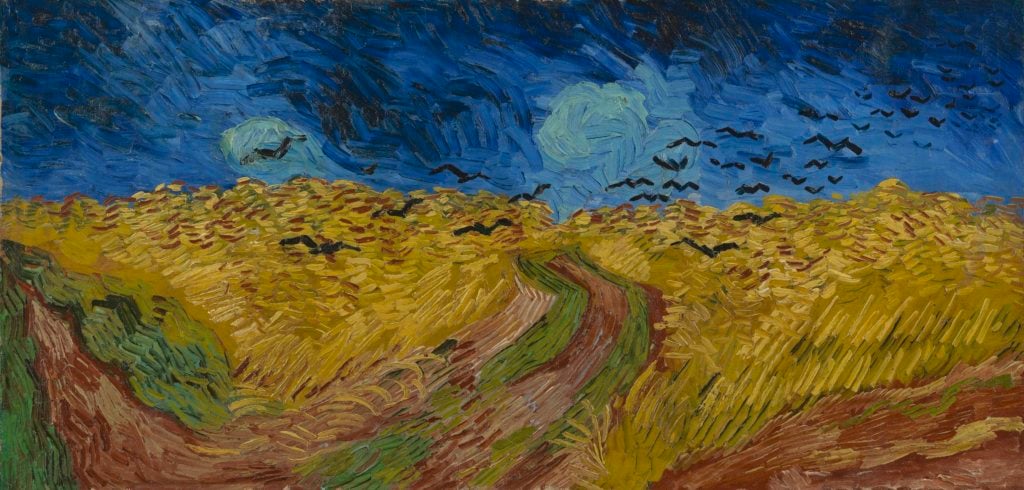

Wheatfield With Crows is a very striking painting that we all know, but it’s partly important to us because it was seen until recently as the last painting he’d done. It’s very difficult to disentangle that thought with our view of the painting.

In general, I think Van Gogh was strongest at doing landscapes when he was at Auvers. It was a lovely place to paint and quite different from Provence. There, the countryside is so dry for much of the time, with more large hills and the Mediterranean cypresses and the olive trees. Auvers is a much more gentle, rolling countryside.

There was the stimulation of working in a new landscape, but also of just being free after being largely behind closed walls at the asylum. Van Gogh was living in a local inn with ordinary people and other artists, so that was more of a congenial atmosphere.

Vincent van Gogh, Wheatfield With Crows (July 1890). Courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum.

In the book, you offer a very detailed refutation of the theory—first detailed in a 2011 biography by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith—that a local teenager named René Secrétan shot Van Gogh by accident. Why are you convinced that story is untrue?

That theory gained a lot of attention. I keep getting asked, “How did Van Gogh die, was it suicide or was it murder?” So I’ve probably produced one of the most detailed accounts of Van Gogh’s death. It’s a forensic examination of what happened, and the conclusion is suicide.

The first time René Secrétan spoke about his contact with Vincent was in 1955, at the end of his life, just a year before he died. He made no suggestion that he had shot Vincent; that was the interpretation of the biographers. If indeed he had shot Vincent by mistake, it would be very curious to bring attention to it after no one had even suspected it.

There’s also a key part of the interview where Secrétan said he left Auvers in July, a week before the death of Van Gogh. When you look at the facts, the evidence that a local teenager pulled the trigger is very flimsy. It all really does point to suicide.

Van Gogh had suicidal tendencies. When he was in the asylum, he ate paint. The doctor said that Vincent said he was thinking of committing suicide. Two of Van Gogh’s siblings had severe problems. A younger brother, Cor, committed suicided in South Africa and a sister, Wilhelmina, had suicidal tendencies and was incarcerated in a mental asylum for nearly 40 years.

After the shooting, Van Gogh said very clearly that he wanted to end his life. Everyone around believed him—Dr. Gachet, the landlord at the inn where he was staying, and most importantly his brother Theo. The police came around to investigate and the mayor witnessed the death certificate. They believed it was suicide. The Catholic priest prohibited the use of the church for the funeral because suicide was immoral.

Van Gogh’s family and friends must have been rather embarrassed, given that suicide was a sin in Catholic France. Had there been any doubt, I’m sure they would have asked the authorities to investigate.

The gun believed to be used by Dutch painter Vincent Van Gogh to shoot himself in Auvers-sur-Oise. Photo by Chesnot/Getty Images.

Why do people seem to want Van Gogh’s life to have ended in a different way?

Everyone is fascinated by Van Gogh’s life. The fact that he’s believed to have killed himself and ended his career is one of the things most people know about his life, along with, of course, the ear incident. People are always interested in an alternative way or shocking new perspective on a historical figure like that.

The last portion of the book is about Van Gogh’s transformation from penniless artist to giant of art history?

Most readers won’t really know much about his rise to fame, because it’s not something that’s written about very often. We all know in simple terms he effectively didn’t sell paintings during his lifetime. Now, of course, 130 or so years later, his pantings fetch huge sums. So what I’ve done in the final part of the book is to chart his rise to fame. I’ve been quite selective and tried to talk about aspects that relate to his last weeks in Auvers and the works that he produced there.

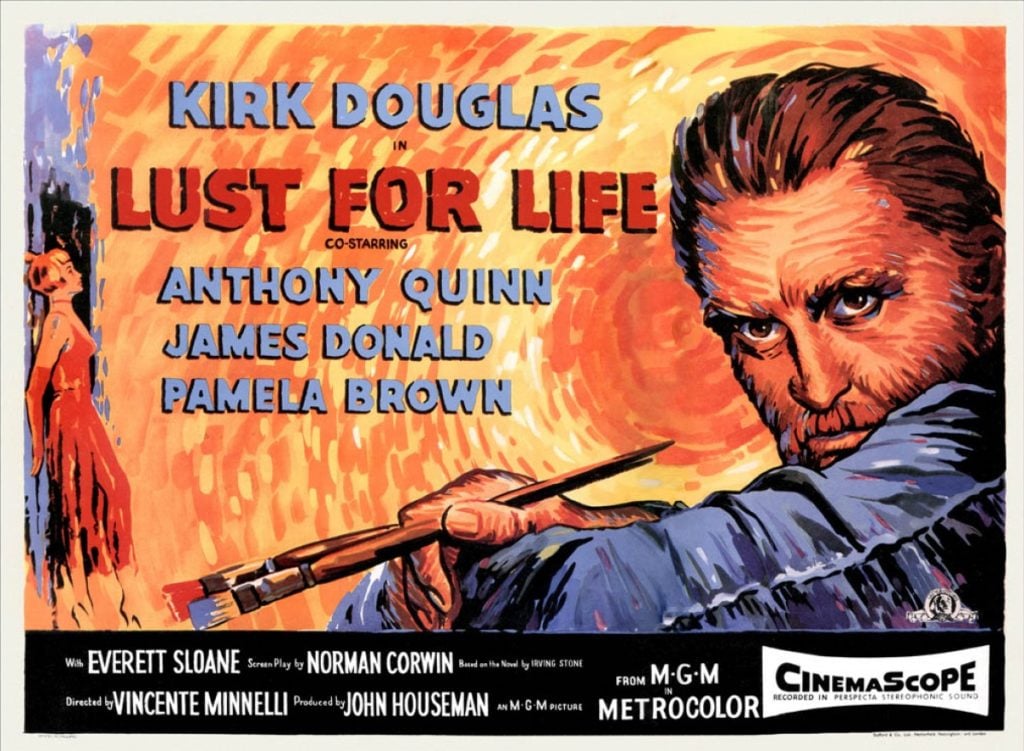

Poster for Lust for Life (1956).

When was the turning point?

It began very soon after Van Gogh died. Initially, he was just known in avant-garde circles in Paris, but his fame really spread and every decade he became more important and the prices ratcheted up. His sister-in-law Jo Bonger published his letters in the 1920s. That generated a great deal of interest in him as a person because we then knew so much about his personal life. The letters played a key role, and also the Lust for Life book that was published in the 1930s by Irving Stone. That was turned into a movie in 1956 that was very popular.

Van Gogh’s life was really made for a novelist. Sometimes fact is stranger than fiction, and it is in this case. He’s been the subject of many books and films, and also pop songs, such as [Don McClean’s] “Starry Starry Night.” There’s an enormous fascination with his life.

What is it about Van Gogh that continues to resonate with people today?

The public enjoys his work for two reasons, I think. The paintings are very accessible. They’re bright, they’re recognizably in his style—superficially they’re attractive, but there’s also depth to them. We’re also fascinated by his personal life, and it was an extraordinary life that he led.

He started off working as a young art dealer in London and Paris and The Hague. He then started learning Latin and Greek because he wanted to become a clergyman. He failed at that and he was a preacher among the miners in the Borinage, a very poverty-stricken area of Belgium. It was at point he set out to become an artist, and he was only an artist for 10 years until his death.

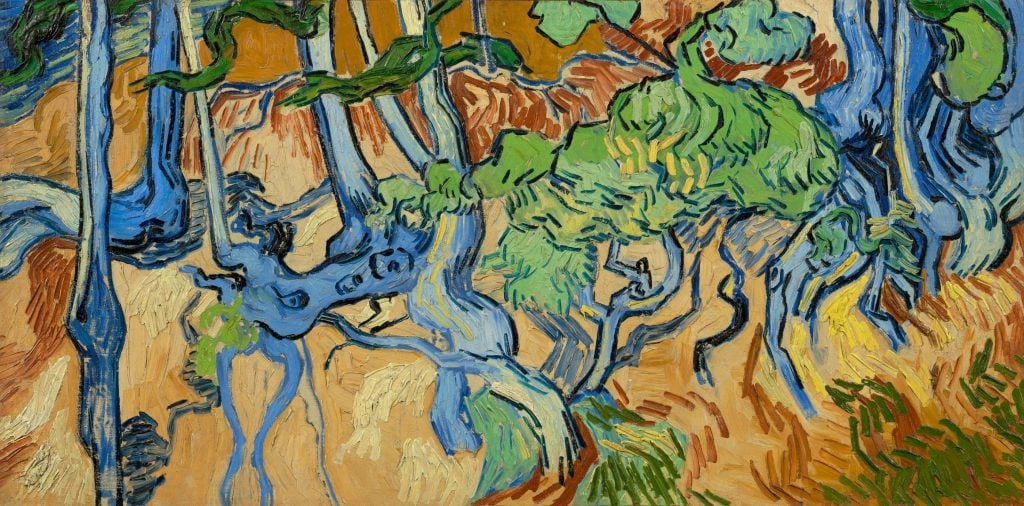

Vincent van Gogh, Tree Roots (1890). Courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, and the Vincent Van Gogh Foundation.

After so many books and all your years of research, is there one thing you wish you could know for certain about Van Gogh?

What exactly was Van Gogh’s medical or psychological problem? That has been studied by hundreds of medical researchers and specialists without coming up with an answer. There was a symposium at the Van Gogh Museum a few years ago about his medical condition and the result was really quite unclear at the end of the day. The only evidence we really have is the letters where Van Gogh occasionally talks about medical issues. But there’s nothing really in that that would lead one to a particular condition. That would be the one thing that I really want to know. That would tell us so much about him as a person, the impact that it might have had on his art, and how we see his ending.