People

How Does a Top Collector Navigate a Very Unusual Frieze Week? We Tagged Along With Muriel Salem Around London to Find Out

Artnet News goes gallery-hopping with a collector on a mission.

Artnet News goes gallery-hopping with a collector on a mission.

Naomi Rea

The regency-era houses that surround Regent’s Park have always held an air of mystery for me. Damien Hirst owns one of them, and I’ve heard whispers about others, but the goings-on beyond those coveted John Nash-designed terraces felt worlds away from the scrappy London I know. (For context: the famous British architect’s other notable residences include Buckingham Palace.)

I finally get to see one up close when I visit art collector Muriel Salem for a whistle-stop tour of a Frieze Week like no other. Stepping over the threshold at Gloucester Gate was like stepping inside the pages of Architectural Digest. The light-filled interior of the Nash house was recently (and artfully) overhauled by Gabriel and David Chipperfield to connect its glamorous front to the more modest mews house at the back of the property.

Muriel Salem. Photo by Naomi Rea.

Salem is the owner of the Cranford Collection, one of London’s most important private collections of contemporary art. Founded in 1999 by Muriel and her husband, businessman Freddy Salem—whose investments include real estate, logistics, and supply-chain management—the collection contains more than 700 works dating from the 1980s onward.

The property has been their home for 30 years. Behind it stands another building that houses the collection’s offices, as well as three bedrooms to accommodate visitors, including artist residents hosted on behalf of the Camden Arts Center. Usually, they’d be chock-a-block around Frieze Week—there could hardly be a better location for proximity to the fairs—but, alas, the bedrooms are empty this year.

Gloucester Gate. Photo by Naomi Rea.

Over tea and biscuits, I ask Salem which room she uses most in the house. “We are Mediterranean, so we follow the sun,” she says. “We start at the East and then make our way to the West!”

Salem came to London from her native Lebanon in 1975 on holiday—but, due to the country’s Civil War, she never left. The collector says she does not know a single person who was not traumatized by the devastating explosion that gutted Beirut over the summer.

“Honestly, we have been in mourning since August 4,” she says. She remains hopeful that Lebanon’s resilience will carry it through this chapter; her native country, she says, has been through “hell and back” before.

Lubaina Himid portrait at the Cranford Collection. Photo by Naomi Rea.

As we walk around, I get a feel for the collection, which is rehung every 18 months. There’s a Georg Baselitz squaring off with a wall-sized Christopher Wool. Martin Kippenberger and Albert Oehlen hang nearby. Even among this macho grouping, works by great women artists sing out. A sparkling Lynda Benglis knot holds court with Franz West, and an Alice Neel contends with Gerhard Richter. Salem practically skips as she points out how a work by Maria Lassnig, “the Austrian radical hardcore,” speaks to a Bridget Riley, “the British Grande Dame.”

The curator of the collection, Anne Pontégnie, who has been working with the Salems for nine years, explains that this hang reflects the collectors’ own evolution. “A lot of women and under-appreciated artists of the 20th century are now being reconsidered,” Pontégnie says. “We really embraced that, and it has opened up new dimensions for us into recent art history.”

My eyes light up upon seeing a portrait by Lubaina Himid—who was largely overlooked by the art establishment until her Turner Prize win in 2017—that was acquired during lockdown. Other relatively recent acquisitions include a Frank Bowling painting and a Lynette Yiadom-Boakye hanging at the top of the stairs.

These are hotly coveted works with skyrocketing prices and lengthy waiting lists. But the curator contends that Salem makes decisions with her eyes rather than her ears. “Muriel stays true to her intuition and follows her heart, even if everyone tells her something is a must-have,” Pontégnie says. “She takes time before committing to an artist, even if that means missing the boat.”

Muriel Salem at Frieze Sculpture. Photo by Naomi Rea.

In any year but this one, a tour of Frieze would involve tripping across the road to the white tents in Regent’s Park. This year, the fair is happening online, but as a collector who values close physical encounters with art, Salem is eschewing the digital surrogate. “I’m an old-fashioned girl,” she says as she dons a chic leopard-print raincoat. “I need to see the work in person.”

It doesn’t take long to reach our first stop. While the physical fair is off, Frieze has decided to mount its sculpture park in Regent’s Park anyway. As we pass an oversize green door by Gavin Turk and a playful concrete sandwich by Sarah Lucas, she opens up about her introduction to collecting in the early 2000s, which began with the acquisition of an altered piece of Eames furniture by the Scottish sculptor Martin Boyce.

“This is the generation that I started collecting British art with,” she says, gesturing to the work by the YBAs. “At the time, it was all happening in London. It was ‘Cool Britannia,’ and everyone was interested in contemporary art. Sarah Lucas, Rebecca Warren, and Gary Hume—that was my cool Britain.”

She also identifies three influential women as her collecting role models. Early on, a visit to Erika Hoffmann’s collection in Berlin was a “very big trigger” for wanting to live with art. Years later, she visited the home of Rosa de la Cruz in Miami and found Esther Grether’s collection in Basel similarly “mind-blowing.” With that, an obsession was born.

A work by Laure Prouvost at Lisson. Photo by Naomi Rea.

We leave the park as it starts to drizzle. I don’t know much about cars, but I can tell the one we climb into is a Porsche. I had also spotted an Aston Martin back in the garage. When I mention it, Salem waves her hand: “It’s for the boys, I have no interest in cars!” (Salem has three sons, as well as one daughter).

We wend our way—through eerily little traffic—to Lisson Gallery in Marylebone, one of the first galleries Salem ever visited. “Nicholas Logsdail [the gallery’s founder] sat me down and taught me all about conceptual art,” she recalls.

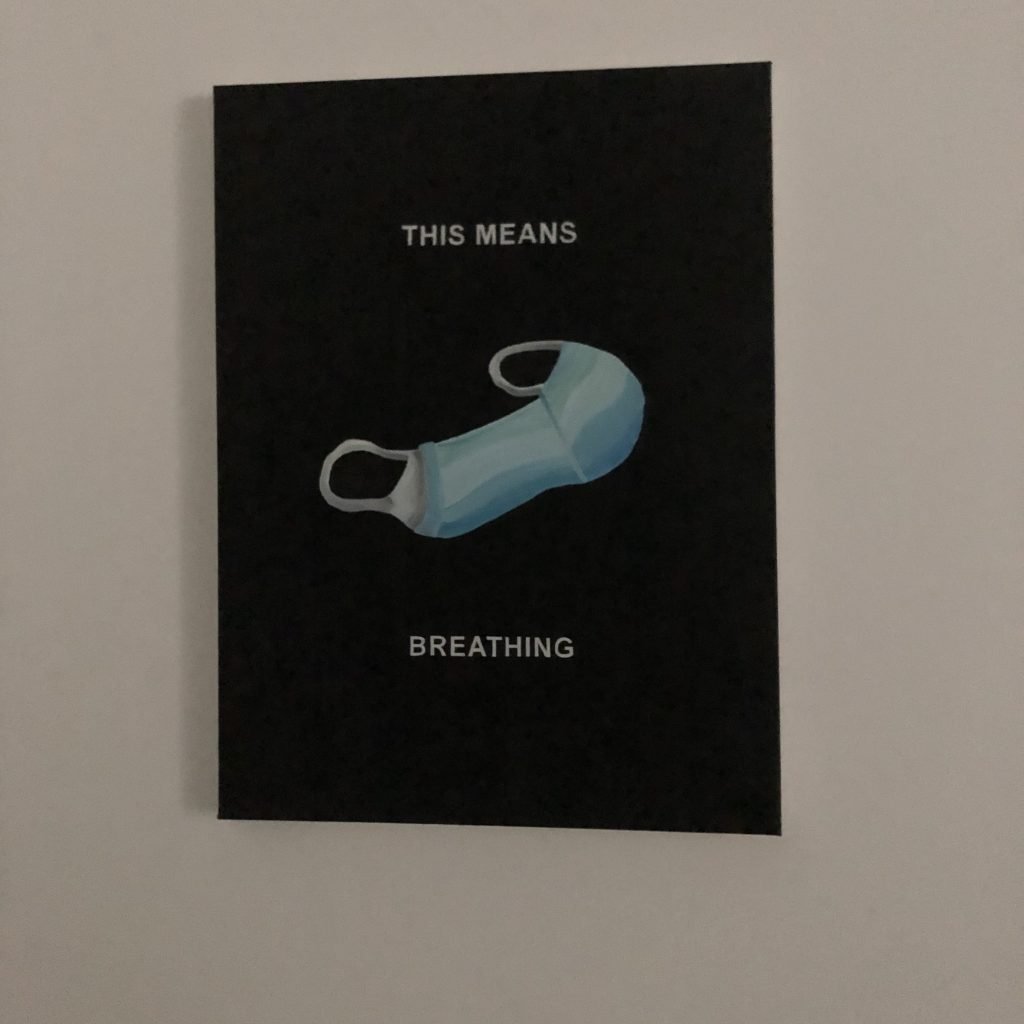

For Frieze Week, conceptual-art queen Laure Prouvost has transformed the space into an “institute of un-learning.” We pass through a bureaucratic queue into an installation in which a series of diptych paintings act like flash cards, teaching us to attach new meanings to certain pictograms. We have fun un-learning our own language and re-learning Prouvost’s lexicon, which tells us that a picture of a shoe means “car” and a roll of duct tape is “bicycle.” A picture of a face mask symbolizes “breathing.”

Eva Langret, the curator and artistic director of Frieze, warmly greets Salem and joins us on our tour. The two easily slip in and out of French as they discuss the installation and the film Prouvost made during lockdown.

Salem owns an edition of Wantee, the work that won Prouvost the Turner Prize in 2013. “I am happy that Laure hasn’t stopped surprising us with her creativity,” she says.

As we stand, socially distanced and in face masks, the show prompts us to compare notes about how the lockdown has forced us to unlearn old habits and re-learn how to be with each other. “The last few years have been quite manic,” Salem says. “We needed to reconsider our behavior and our values—but of course I’m sorry that it happened in this way.”

Eva Langret and Muriel Salem speak with François Chantala, partner at Thomas Dane Gallery. Photo by Naomi Rea.

Langret joins us on a trip to Mayfair to see the first UK solo show by American painter Dana Schutz at Thomas Dane. On the way, Salem confesses that Schutz is one of the artists she has been eyeing for the collection for years.

As we stand before Schutz’s Goya-inspired Large Model, the collector admits she has been “struggling” with Schutz’s grotesque figures for some time. But this year, she hopes, she will find the right piece.

At the gallery, we bump into Maria Balshaw, the director of Tate galleries, who artfully dodges a question about the week’s hot topic—the cancellation of a highly anticipated Philip Guston exhibition—and listens intently to Salem’s thoughts on Tate Modern’s sprawling Bruce Nauman retrospective.

Before heading out, we pop downstairs to the basement, where the gallery is showing works from its digital Frieze presentation IRL. It’s not technically open when we sneak a peek—and it definitely feels overshadowed by Schutz’s riotous paintings upstairs.

Muriel Salem speaks with Pippy Houldsworth. Photo by Naomi Rea.

We bid adieu to Langret, who is late for a Zoom talk, and head a few streets over to Pippy Houldsworth Gallery. While the gallery is technically not part of the official Frieze program, Salem is keen to catch the show of the rising star painter Jadé Fadojutimi.

We are both quite taken by the frenetic and colorful works in “Jesture,” most of which were made during lockdown. Houldsworth steps out of a meeting to greet us, and Salem gently queries about availability.

“Nothing is available,” Houldsworth says. “A lot of it is going to museums.”

While this is believable—Fadojutimi is the youngest artist currently in Tate’s collection and has just been profiled in Vogue—I ask Salem over lunch whether that response is not just part of the obligatory courting dance that happens when you buy art.

Over truffle and ricotta tortelloni, she confides, “It is often like this, but if it was really the case every single time, we would have nothing in our collection.”

It took 20 years to build the collection she has today. “We weren’t always welcome,” she says. “Some [dealers] refused to sell to us, or ignored us, or snubbed us. But you have to start the conversation somewhere.”

Art fairs are usually a good place to do that—but they don’t always lead to quick sales either. “There’s always some discovery, or an unexpected encounter,” Salem says, recalling the first time she came across Lubaina Himid’s work at Hollybush Gardens’s small Frieze booth. The conversation that started there resulted in the acquisition of the portrait I saw back at Gloucester Gate five years later.

Install image, Frank Bowling, According to Lorca (2019). The Cranford Collection, photo by Richard Ivey.

Post-Frieze, a selection of works from Salem’s collection will go on view at MO.CO., the novel museum of private collections in Montpellier. The exhibition, which opens next month, is descriptively titled “The 2000s,” and includes more than 80 works by 44 artists ranging from Cindy Sherman to Sigmar Polke.

It’s nearly 5 p.m. now, and the collector has to run. She is headed to Whitechapel Gallery, where the collection has loaned a work by Kai Althoff to the artist’s first public exhibition in London. She’ll pick up Freddy on the way.

“00s. Cranford Collection: The 2000s,” is on view at MO.CO. Hôtel Des Collections in Montpellier, October 24 through January 31, 2021.