People

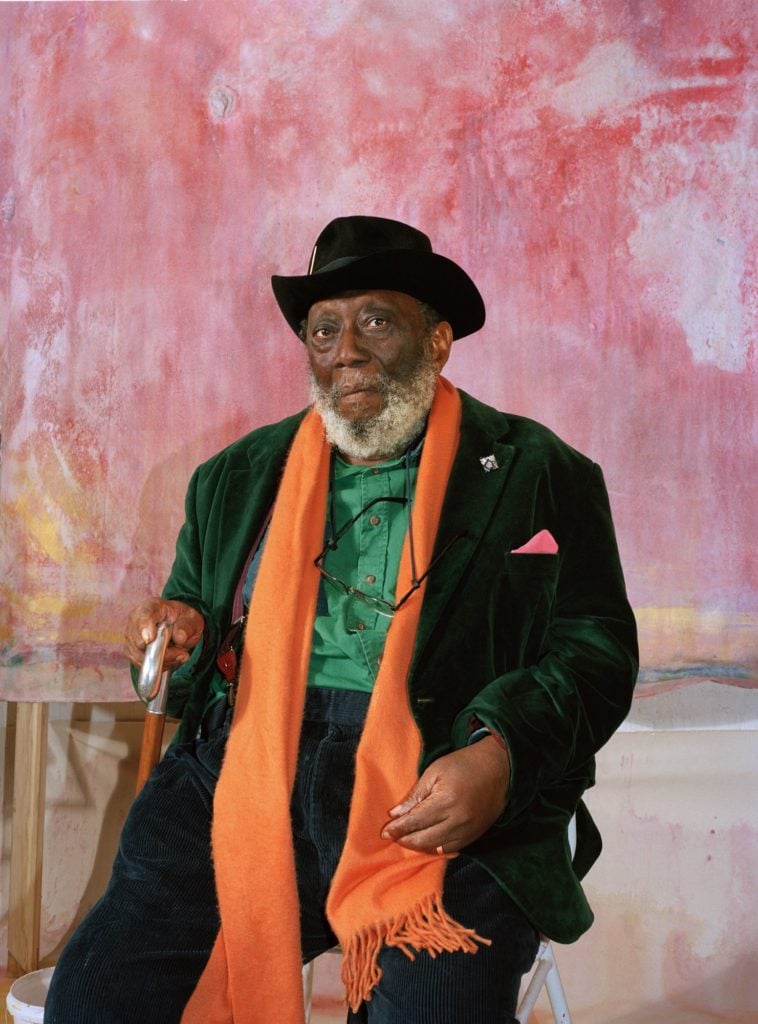

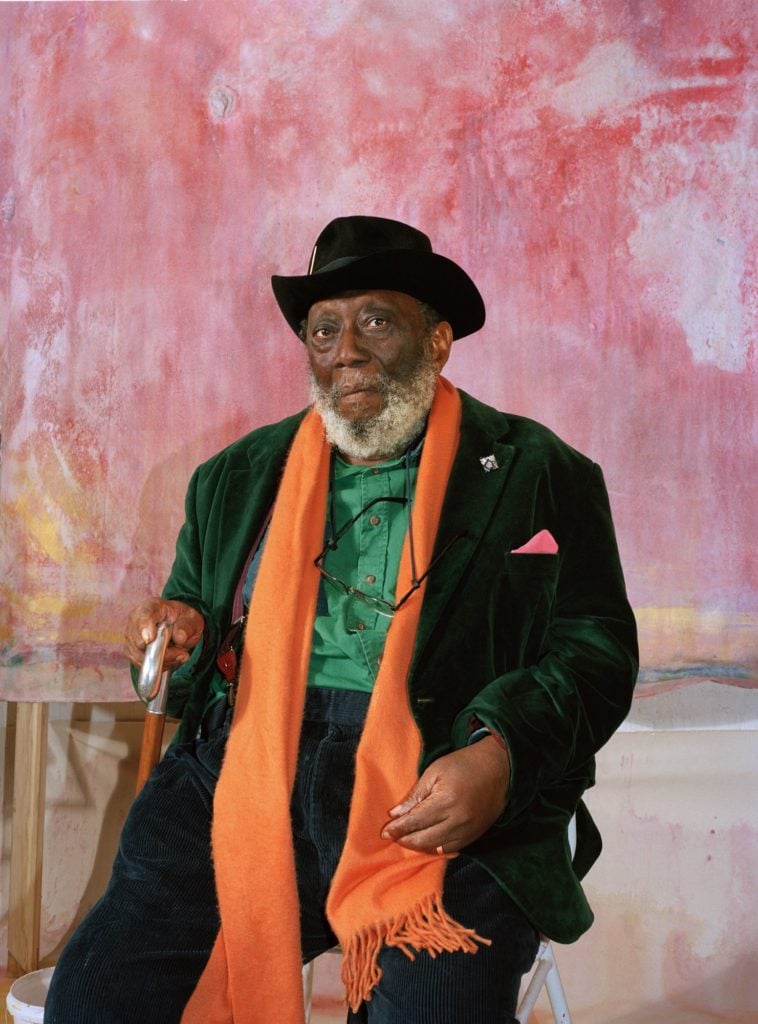

After Decades of ‘Appalling’ Institutional Neglect, Museums Are Now Clamoring for Artist Frank Bowling’s Work

The veteran artist's virtuoso paintings are currently on view at Tate Britain.

The veteran artist's virtuoso paintings are currently on view at Tate Britain.

Javier Pes

Art dealer Paul Hedge is getting “10 calls a day” from curators and collectors interested in veteran artist Frank Bowling’s vibrant paintings. But Hedge, the co-director of London’s Hales Gallery, is cautious about who gets to buy work by the 85-year-old artist, who, after decades of institutional neglect, including by the museum on his doorstep, is now in demand. It is a similar story in New York, where the artist is also based.

“It would be tragic for Frank to just become a commodity before he is given his rightful place in the canon,” Hedge tells artnet News. He reveals that he and his colleagues have also been kept busy reading Evelyn Waugh’s tragic-comic novel A Handful of Dust ahead of Art Basel this week because of Bowling.

Why get up to speed with Waugh’s satire of the English upper classes, which was published the year Bowling was born, in what was then British Guyana? “Frank’s reaction was all about the way Waugh described the Guyanese jungle,” Hedges says. “He really took exception to that.” As a result, Bowling painted a series of “Cathedral” paintings in 1987 that Hales is presenting in its solo booth at Art Basel.

“His prices are still sorely undervalued, but you have to start somewhere,” Hedge says. The artist’s smaller canvases range from $250,000 to $500,000. The artist’s auction prices lag behind, partly because only smaller works have been sold recently, Hedge explains. (The artnet price database lists a 2010 acrylic that sold for $146,000 at Phillips in March, for example.)

Frank Bowling, South America Squared (1967). Rennie Collection, Vancouver. Copyright the artist. All rights reserved DACS.

Hedge says that he and Bowling, who are following a “long-term strategy,” are more interested in where the works go. “If someone is on the West Coast and says they intend to donate it to a museum there, [Bowling’s] family is much more willing than just selling them to random speculators,” he says.

As it happens, Bowling’s New York gallerist, Alexander Gray, who began representing Bowling there two years ago, has just placed a large new work, Elder Sun Benjamin (2018), with a “major West Coast institution.” Gray acknowledges Hedge’s efforts in developing the artist’s market and bringing his work to the fore. A decade ago, when Gray first got to know the artist, interest in his work was “nascent” at best, Gray says. Now, Bowling’s large canvases are selling for more than $1.5 million, he says. Many of those paintings have been rolled up in the artist’s studios in New York and London during decades of institutional neglect.

One of the reasons for the surge in interest is Bowling’s retrospective at Tate Britain—a first for a black British artist—which opened on May 31. The artist has lived within blocks of the museum for the past three decades. He can sometimes be spotted studying the J.M.W. Turners in its Clore Wing.

A major museum survey has been a long time coming on either side of the Atlantic given that Bowling had his first solo museum exhibition at the Whitney in 1971. Tate did not acquire one of his works until 1987. “He was born in South America, became a black British artist, and then a British artist in America: his biography is inconvenient,” Gray says diplomatically.

The Guyana-born artist Hew Locke remembers hearing his father, the artist Donald Locke, and Bowling arguing intensely about art. They were part of a generation who had to fight an uphill battle for recognition in the art world. Locke cites Aubrey Williams (1926-90) as another painter of the so-called Windrush Generation who also moved to Britain. “Nobody gave a shit, frankly,” Locke says. Bowling, like his father and Williams, were overlooked partly because they were black artists who could not be placed in the pigeonhole of more openly activist black art.

Locke says that Bowling only really began to get the recognition he deserved when his paintings were included in a group show during the 2003 Venice Biennale. Some of the work in the show had been rolled up in his studios for three decades. He pays tribute to the US academic Courtney J. Martin who as a guest curator organized a room of Bowling’s 1970s poured paintings at Tate Britain in 2012. “The vibe was it should have been a full exhibition,” Locke says.

Installation view of “Frank Bowling” at Tate Britain (2019). Photo: Tate Photography, Matt Greenwood.

Martin, who is the incoming director of the Yale Center for British Art, was not alone. In 2005, Bowling’s fellow artists recognized his achievement by electing him a Royal Academician, the first black artist to be so honored. The late, great curator Okwui Enwezor organized “Frank Bowling: Mappa Mundi” at the Haus der Kunst in Munich, shortly before his own death. As in Venice, the 2017 exhibition in Germany included paintings that had long been rolled up and never previously exhibited.

The same year, Pace in London included several of Bowling’s paintings in its group show “Impulse.” His experimental canvases were placed in the context of work by contemporary color field and abstract artists, including Kenneth Noland, Morris Louis, and Sam Gilliam. Tamara Corm, who organized the Pace show, says that along with increased institutional visibility, the rise in Bowling’s market is partly due to the new power of African American collectors, such as Pamela Joyner.

Installation view of “Frank Bowling: Make It New” (2018). Courtesy of Alexander Gray Associates, New York.

Bowling’s paintings look set to increase in visibility (and value) as museums seek to diversify their collections. The Minneapolis Institute of Art has recently acquired Bowling’s work False Start (1970). It is now a centerpiece of its display “Mapping Black Identities.”

The Menil Collection in Houston has owned a large and powerful painting by Bowling since the early 1970s. Called Middle Passage (1970), it went on show at Rice University then, and is now is a key loan in the Tate’s touring exhibition, “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power.” The painting, along with Bowling’s Tambernic Tumbles (1975), which Dominique de Menil acquired in 1976, were for five decades mainly kept in storage, a situation Paul Hedge calls “appalling.” That changed when Rebecca Rabinow became the Menil’s director in 2016. She and senior curator Michelle White hung Bowling’s works in one of the museum’s most prominent positions: the lobby.

Hedge says that there is a long way to go in fully understanding Bowling’s achievement as an artist and a writer. “No one has discussed the sublime in his work. His relationship with America is yet to be discussed in any great detail. He lived for a time next to Donald Judd on Spring Street,” Hedge points out. Like Judd, Bowling’s writings have been influential and, Hedge points out, “His letters to [his friend, the critic] Clement Greenberg are wonderful.”

Bowling, like his contemporary David Hockney, is still painting big, colorful canvases. The Royal Academicians were fellow students at the Royal College of Art in the 1960s. (Bowling won a silver medal the year Hockney won a gold one.) Albeit from a very different starting point, the price of Bowling’s work is set to soar, too.

“Frank Bowling: The Possibility of Paint are Never-Ending,” May 31 through August 26, Tate Britain, London.