A year ago last month, the Supreme Court put its stamp of approval on a sweeping executive order banning nationals from seven countries, mostly majority-Muslim and in the Middle East, from entering the US. From artists with household names to newly minted MFAs, and from global institutions to small nonprofits, the ban has had effects that cut across the art world, continuing to unfold into the present.

In the name of national security, the original January 2017 order barred nationals of Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen, including large numbers of refugees. Led by organizations including the ACLU, the resulting legal battle ended in June 2018, when, in a 5-to-4 ruling, the Supreme Court upheld the ban, since revised to remove Iraq and Sudan, and to add Venezuela and North Korea.

Many in the arts, however, share the suspicion that the ban was about racism and the whims of the Trump administration rather than security. The artist Shirin Neshat, who spoke to artnet News in a phone interview while preparing a survey exhibition at Los Angeles’s Broad Museum, connected the climate of anti-Muslim discrimination and the government’s treatment of migrants and refugees in detention camps along the US’s southern border, saying they shared a common motive.

Her words were sharp: “It’s so evil.”

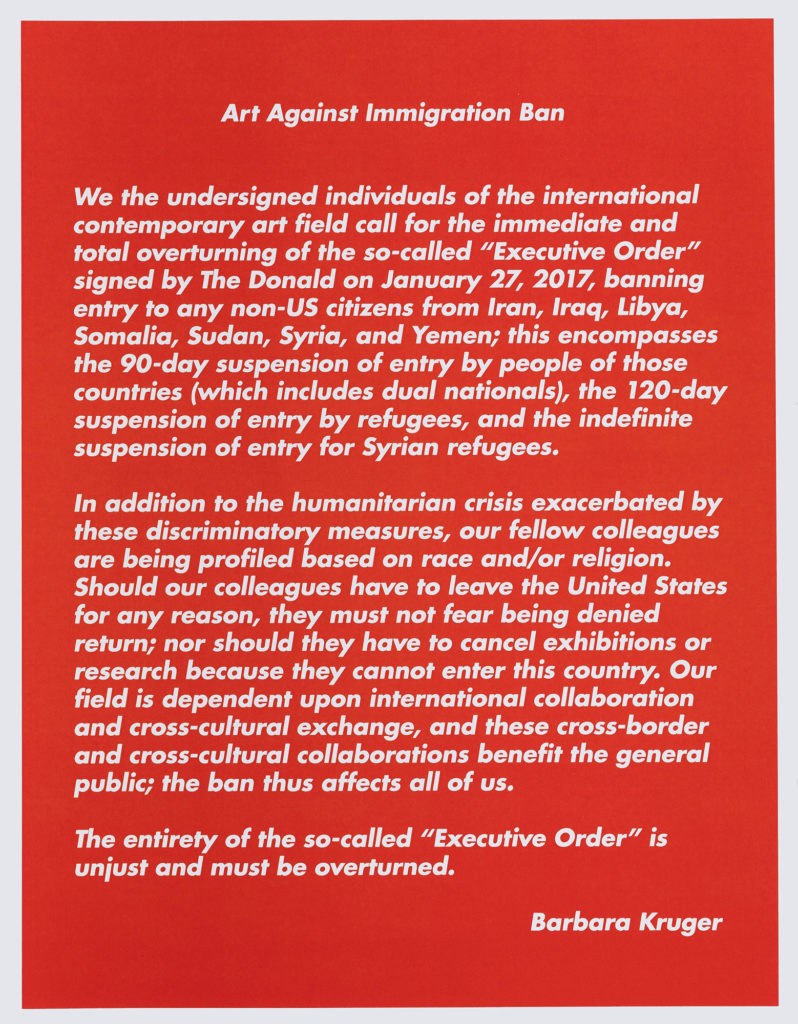

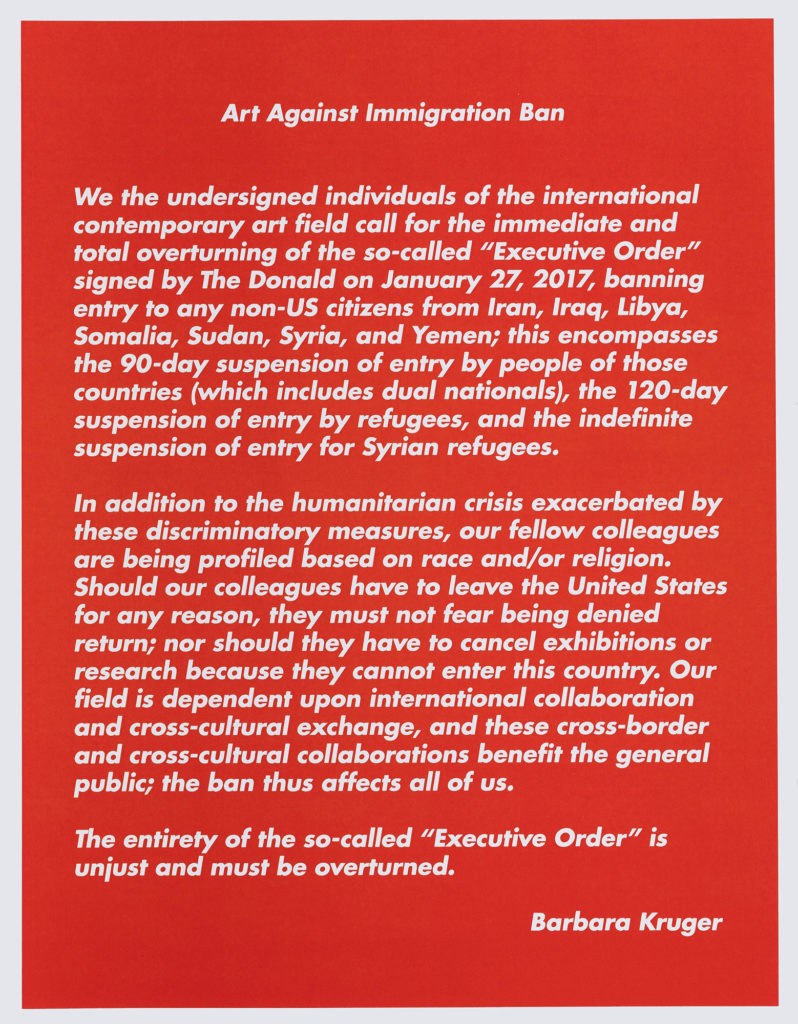

Barbara Kruger, Art Against the Immigration ban poster (2017). Courtesy of the Guggenheim.

‘A Struggle to Survive’

“There’s no way to fully communicate to the American public the effect this is having on the citizens of the banned countries,” says Iranian-born media strategist Mahdis Keshavarz, who lives in the US and whose clients include artists and arts institutions. “Artists especially have no other means of economic survival.”

For artists within Iran, known for its thriving artistic culture, US economic sanctions have created a particularly disastrous situation, effectively shutting down a lot of the art market. “Galleries and artists have lost the opportunity to sell to outside clients, in particular Americans,” says an Iranian dealer living in New York who spoke on condition of anonymity. “People can’t afford to eat anymore. Artists come to my house with tears in their eyes because they can’t pay next month’s rent. It’s a struggle to survive.”

Thana Foroq, Everyday Yemen series. © Thana Foroq, courtesy of the artist.

The travel ban means that artists from affected countries also find themselves cut off from prospects such as international residency programs that introduce them to broader networks, as well as from traveling to exhibitions abroad. “It leaves you isolated, quite literally,” says Yemeni photographer Thana Faroq, now living in the Netherlands, “just when I’m at a point in my career where I feel my work could reach a greater audience.”

Those who come to the US for education can also pay a steep personal price. Iranian-born artist Sareh Imani, living in New York after earning an MFA from Parsons School of Design and holding an O1 visa, finds herself separated from her close-knit family in Iran. Her family members cannot travel here, and even though they have Canadian visas, she says, she can’t meet them in Canada because the terms of her own visa dictate that if she leaves the US, she can’t come back.

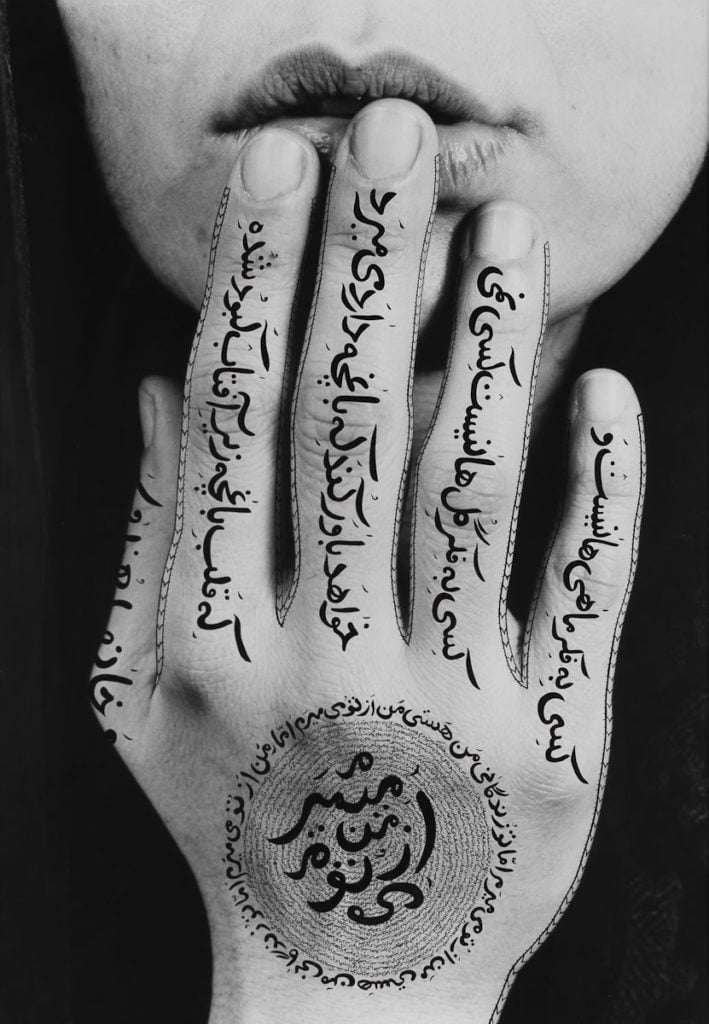

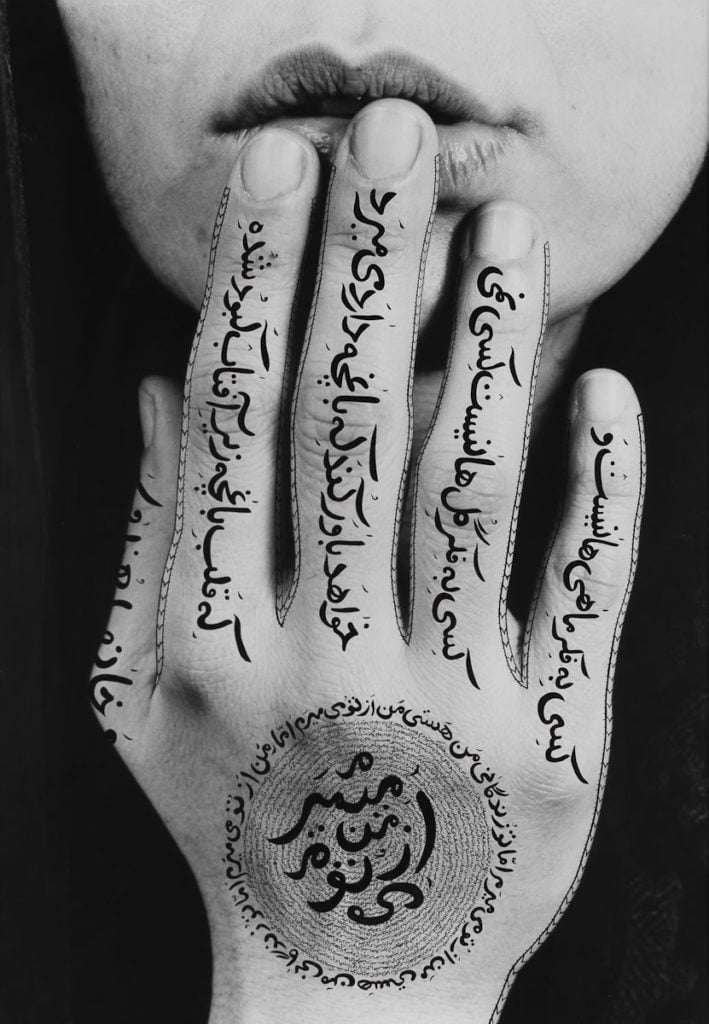

Shirin Neshat, Untitled, from the series “Women of Allah” (1996). Photo ©Shirin Neshat, courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.

Iran-born Neshat, who has lived in the US since 1975, points out that even those fortunate enough to have US citizenship or a visa may be separated from their loved ones for decades. “I can’t go back to Iran because I have problems with my own government, and my family cannot come here, so we are both hostages in our own country. You so easily accept that you don’t go home for thirty years. It’s inhumane but unfortunately you get used to it—with a lot of melancholy, of course.”

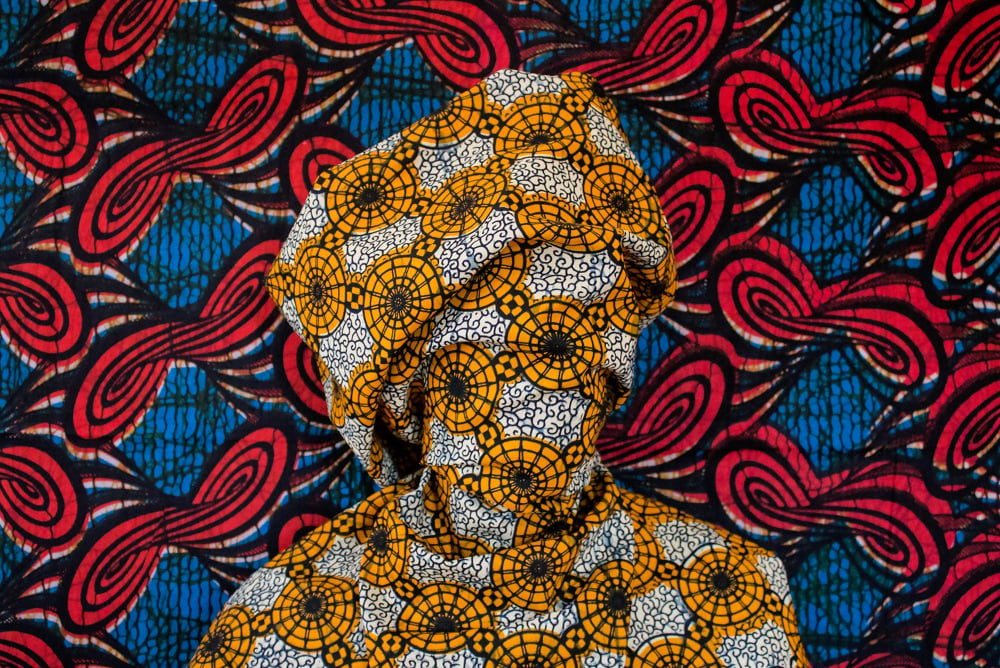

Yemeni artist Alia Ali experiences the ban not only as a career disadvantage but as a direct impediment to her work itself. Now a naturalized US citizen living in Los Angeles, the artist was born in 1985 to a mother from the former Yugoslavia and a father from what was then South Yemen. Having earned a BA at Wellesley and an MFA at the California Institute of the Arts, cross-cultural engagement has become part of her artistic identity. “A big part of my education was to travel,” she explains, “and so this has eventually become the very fabric of my work, engaging with a myriad of cultures different from my own.”

The consequences for Ali have been far greater than missed opportunities. The artist found herself unable to visit her dying grandmother in Yemen.

Conversely, Mahdis Keshavarz says that relatives in Iran were unable to visit her father when he took ill and died in the US in February 2017, during the early days of the ban.

Cultural Exchange, Thwarted

“It’s still difficult to know how applications will be treated,” says Ashley Tucker, an immigration lawyer and director of programs at the New York nonprofit Artistic Freedom Initiative. AFI provides an array of services for artists, writers, and others wishing to immigrate, including those facing oppression at home. Because travel restrictions lessen artists’ ability to disseminate their work, she says, AFI is invested in helping those affected by the ban—but that has become extremely unpredictable terrain in the wake of the Supreme Court decision.

“There are still no protocols,” she says. “It’s the Wild West of immigration lawyering.”

Meanwhile, museums have had to rethink their own initiatives towards cultural exchange. Institutions large and small regularly organize trips for their patrons to Iran, during which collectors and curators deepen their ties to the country’s art scene. Following a State Department advisory, institutions including New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art both put a freeze on plans for travel to the Islamic Republic.

“It’s sad,” said LACMA’s curator of Islamic art, Linda Komaroff, “because cultural exchange is exactly what we need now.”

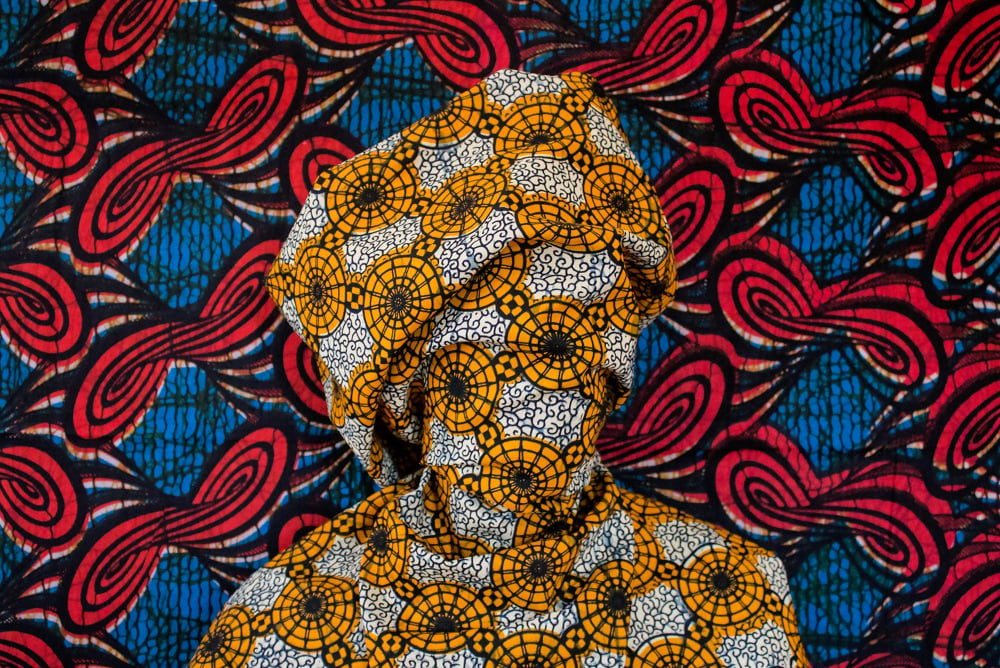

Alia Ali, Infinity from “Borderland Series” (2017). Courtesy of the artist.

Smaller organizations have also found their work affected. One exhibition curator, Hilal Khalil, an attorney by day who co-organized “Mark for Redaction,” at Flux Factory, in Queens, New York, pointed out that customs officials have shown a seeming wariness even of work coming from US allies in the region. “Art from Saudi Arabia was held up in Customs and didn’t make it by the opening, and Saudi Arabia isn’t even covered by the ban,” he said.

The Flux Factory exhibition, highlighting work by LGBTQ+ artists from Southwest Asia and North Africa, was to be co-organized by Khalil with Lebanese filmmaker Razan Al-Salah. When Al-Salah traveled to Canada during the planning for the show, she found herself unable to return to the US and had to resettle there.

Conflicted Hopes

Despite restrictions, those affected by the ban speak hopefully, or at least poetically, of the possible transcendence of national boundaries.

“The power of the artist is their ideas, and ideas have no borders,” says Alia Ali.

“I’m planning for a better world—if I live that long,” says Komaroff.

But others are not as sanguine about future prospects, and see the climate of fear reaching deeper and deeper into the fabric of the art world. “When does the censorship extend to the art?”, asked Khalil. “What if it was found out that I had Iranian art in my show? When do the sanctions start to prevent ideas from coming in?”