What I Buy and Why

The Roving Eye of Australian Philanthropist Naomi Milgrom and Her Latest Fascination, Collecting Pavilions

The latest architectural pavilion she commissioned, by Tadao Ando, runs through March 2024.

Australian collector and patron Naomi Milgrom doesn’t compartmentalize. “My philosophy on collecting is pretty simple,” she told Artnet. “It’s based purely on what I love, and it includes all forms of creativity—visual arts, architecture, design, music, fashion.” In other words, everything. Particularly—though not exclusively—disciplines that sit outside the realm of painting, with an emphasis on the tactile or technological.

At her home in Melbourne, which she commissioned from American architect Richard Gluckman, the fashion magnate has acquired works by Bridget Riley, Gillian Wearing, Tacita Dean, Tatiana Trouvé, and sound artists Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, as well as William Kentridge, Anselm Kiefer, and Chris Ofili. There is also a site-specific work by Ugo Rondinone and a series of cut-paper collages by Henri Matisse, plus sculptures by Franz West and Alexander Calder, and a monumental Richard Serra piece painstakingly installed in her garden after a ride on a freighter halfway around the world. And let’s not forget furnishings by Le Corbusier, Oscar Niemeyer, and Vico Magistretti, plus Venetian glass by Barovier & Toso, tapestries by Sonia Delaunay, and floor rugs by Marta Maas Fjetterstrom.

Some of the above pieces have been displayed in the headquarters of her retail conglomerate Sussan, which in 2008 was converted from a disused factory by Sydney architects Durbach Block. These include works by Sol LeWitt, Seydou Keïta, Andreas Gursky, Thomas Demand, and a site-specific mural by Richard Long made from the mud of the Yarra River, on which the offices sit.

Milgrom’s commitment to the arts doesn’t end with her personal collection. She’s constantly lending out works, commissioning performances, and sponsoring events. In 2017 she served as Australia’s commissioner for the Venice Biennale, which led to a unique friendship with Tracey Moffatt—her “hero”—that began when she called the Australian Indigenous artist with the news that she’d been selected to represent Australia.

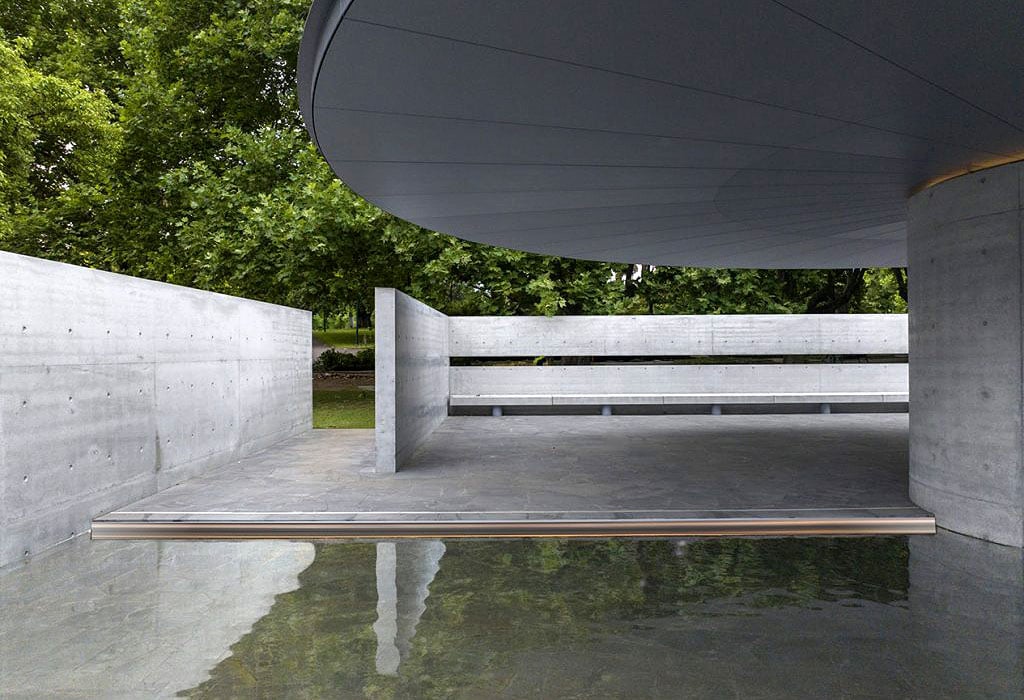

Tadao Ando’s pavilion for MPavilion. Photo: John Gollings

Then there are the architectural pavilions. In 2014, Milgrom established MPavilion, an annual architecture and design festival through which she’s collaborated with some of the world’s leading urban thinkers. After five months of civic service in Queen Victoria Gardens in central Melbourne, during the hemisphere’s sweltering winter months, the pavilions are donated to local universities. Previous pavilions have been designed by Rem Koolhaas, Bijoy Jain, and leading Australian architects Glen Murcutt and Sean Godsell. Tadao Ando is the 10th and latest MPavilion architect (through March 2024), marking the Pritzker winner’s first Australian commission. Minimalist ice cream sold there comes in six shades of concrete gray and the flavors are not labeled.

Milgrom has received an array of awards and accolades. In 2020 she was named an Honorary Fellow of the Design Institute Australia. She served as a judge for the World Architecture Awards (2015–2021) and chair of the Sydney Parramatta Powerhouse International Design Competition (2019). In addition to her work with the Venice Biennale, she serves on the International Councils for London’s Tate Modern and New York’s MoMA, as well as the Global Patrons Council for Art Basel.

We caught up with the trailblazer to speak about her remarkable collection and her dedication to the art scene down-under.

What was your first purchase?

During my university years, I made my first art purchases, both works by Australian artists—Howard Arkley and Rosalie Gascoigne. They’re two very different artists, but they both made work very closely related to our Australian surroundings—the city and the country.

Rosalie Gascoigne Harvest (1982). Photo: John Brash. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney.

Arkley was fascinated by Australian suburbia, and the architectural features and interior décor of suburban homes. The bold pop colors applied to his canvases with airbrush tools invited us to celebrate the domestic. Sadly, Arkley died of a drug overdose two weeks after the opening of his critically acclaimed exhibition at the Venice Biennale of 1999.

There are many links between the artists in my collection, and interestingly one of the artists Arkley was heavily influenced by was Bridget Riley, who has made some of my favorite works in my collection.

Rosalie Gascoigne began her artistic career later in life. She had no formal art school training, other than classes in ikebana, and she had her first exhibition at age 57. Choosing seemingly simple materials sometimes drawn from the landscape but often marked in some way by the passing of time, Gascoigne created profound and beautiful works. She, too, represented Australia at the Venice Biennale, the first woman to do so, along with Peter Booth in 1982.

What was your most recent purchase?

Recently I bought two works, a Bridget Riley black-and-white gouache on paper titled Oval Movement within Disks from 1964 and a Tracey Moffatt work called Up in the Sky from 1997. The Bridget Riley work is an addition to my collection of black-and-white works from the ’60s.

Bridget Riley, Oval Movement within Disks (1964). © The artist.

The Tracey Moffatt is a group of 25 images that read like stills from a black-and-white movie, set in an Australian outback town desolated by poverty, violence, and despair, somewhat reminiscent of the Australian apocalyptic road movie Mad Max. She is a photographer and filmmaker who ‘makes’ rather than ‘takes’ pictures. Her work draws on a rich mix of her childhood memories, personal experiences, popular culture, history, film, television, and literature.

My close association with Tracey began in the 2000s when I was the Australian commissioner for the Venice Biennale. I couldn’t believe my luck when I had the enviable task of personally letting Tracey know she had been selected to represent Australia at the 57th International Art Exhibition. It was a thrill to make that call. My relationship with Tracey began the moment she answered the phone.

It was the first time an Indigenous person represented Australia in a solo exhibition, and we were an all-female team! We are two women with different life experiences, seemingly with little in common, but over time we have discovered just how much we actually share, and now enjoy a deep, unexpected friendship.

She approached our time working together with dedication, focus, discipline, and a ferocious commitment to producing two extraordinary suites of entirely new photographs and two new films for the Biennale in 2017. Tracey is my hero.

Henri Matisse, Jazz (1947). Photo: Christian Capurro. Courtesy of Naomi Milgrom.

Tell us about a favorite work in your collection.

Can’t choose one, way too many favorites. My top three, perhaps, are Henri Matisse‘s Jazz (1947), William Kentridge‘s drawing for 7 Fragments for Georges Méliès, Day for Night and Journey to the Moon (2003), as well as Sonia Delaunay’s tapestries Rhythms Ondulatoires and Automne, both ca. 1970.

Jazz really doesn’t need any explanation, it’s just a work of pure joy and beauty, an overwhelming celebration of everything! I cannot think of a better way for my senses to be woken every morning. And I waited a very long time to be able to acquire this work.

Installation view of William Kentridge’s “That which we do not remember” at Art Gallery of South Australia, 2019, including Drawings for 7 Fragments for Georges Méliès, Day for Night and Journey to the Moon (2003). Photo: Paul Steed.

I have been collecting William Kentridge’s work for over 20 years and this one is definitely a favorite. It’s like the backdrop for a film—layer upon layer carefully placed, a full-scale replica of William’s studio right down to the chair he sits on. William said he did it like that to remind himself that the journey to the moon doesn’t need to step beyond the bounds of the studio itself. I was so happy to share this work and the rest of my collection of Kentridge’s films and drawings in an exhibition titled “That which we do not remember,” which travelled from Sydney to Adelaide in 2018–2019.

Sonia Delaunay, Rhythms Ondulatoires (Rhythms Wave) (ca. 1970). Photo: Christian Capurro. Courtesy of Naomi Milgrom.

My absolute favorite tapestries are by Sonia Delaunay, striking in their color, composition, and dynamism. Is there a theme here? I love the three-dimensional nature and texture of this medium. Seeing these works makes me reminisce about an exhibition I visited more than a decade ago at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, “Léger: Modern Art and the Metropolis.” What a breakaway exhibition that was, one of the earliest multi-disciplinary exhibitions I saw. It included music, film, painting, advertising, design, and architecture. Sonia Delaunay was one of Léger’s many contemporaries featured.

The tapestry will be loaned to Art Gallery of South Australia for the exhibition “Radical Textiles” curated by Rebecca Evans and Leigh Robb, to be held from November 23, 2024 to March 30, 2025.

What is your philosophy when it comes to collecting?

Collective creativity is a powerful mindset that I’ve always been drawn to. I value a strong collaborative ethos which values positive co-dependency and shared success.

My approach to collecting is a natural extension of the support I give—both personally and through my foundation—to artists, designers, and architects so I can best aid them in involving communities and exhibiting artworks publicly. For example, it was with great joy that I supported William Kentridge in the realization of The Head & The Load, an opera at Tate London in 2018 and for a major traveling exhibition in Australia, “That which we do not remember” at AGNSW in 2018 and AGSA in 2019.

Similarly, I really wanted to give my fellow Australians the opportunity to experience Philip Glass’s work in person and supported the presentation of Einstein on the Beach at the Arts Centre in 2014, Tao of Glass at the Perth Festival after its premiere in Manchester in 2019, as well as Matthias Schack-Arnott, who created a phenomenal sound installation called Groundswell for the Sydney Festival and Adelaide Festival in 2021 and Melbourne Fringe in 2022. I’ve been involved in many exhibitions through lending my works, including the recent “Gillian Wearing: Editing Life” exhibition at ACMI in 2022, presented as part of PHOTO 2022, which featured Gillian Wearing’s Rock ‘n’ Roll 70 Wallpaper.

Installation view of Gillian Wearing’s “Editing Life” with Self Portrait of Me Now in Mask (2011), Self Portrait at 17 Years Old (2003) and Rock ‘n’ Roll 70 Wallpaper (2015), presented as part of PHOTO 2022 in Melbourne, Australia. Photo: Mark Ashkanasy. Courtesy of Naomi Milgrom.

I work in a similar way when making commissions and love supporting creatives directly, especially so for the MPavilion, the flagship initiative of my foundation. I’m very proud to say that over our first decade, we’ve become Australia’s annual leading architecture and design commission, set apart by the way we’ve commissioned nine of the world’s leading architects and more than a hundred designers and creative talent in a multitude of different fields—art, furniture, lighting, music, books, fashion, food, etc. It’s wonderful, none more so than the Wominjeka Song Cycle by Deborah Cheetham Fraillon AO, Indigenous soprano and director of the Short Black Opera. That commission spans 10 years and evolved with MPavilion. Each song sonically represents a particular pavilion; together the cycle celebrates an enduring yet dynamic place and the knowledge we share and create in it.

Which works or artists are you hoping to add to your collection this year?

Recently I had the great pleasure of meeting Michael Elmgreen. His work with Ingar Dragset has fascinated me since the Prada storefront in Marfa was built late in 2005. Being in the fashion business myself, the irony of a luxury store in the middle of nowhere was not lost on me! Michael told me that Miuccia Prada herself supported the work and supplied the product—shoes and handbags—and was a terrific collaborator. So, I am keen to add a work by Elmgreen & Dragset to my collection.

Fourteen works on paper by Bridget Riley dating from 1961 to 1966, © The artist, with William Kentridge’s Nose I (Scissors) (2007) on the table and Alexander Calder’s mobile Untitled (1974) in the adjoining room. Photo: Christian Capurro. Courtesy of Naomi Milgrom.

What is the most valuable work of art that you own?

My collection of Bridget Riley black-and-white works on paper from 1961–1966 is definitely my most valuable from a sentimental point of view. I’ve been buying these works for over 18 years, patiently waiting for just the right work to add to my collection.

Riley is one of my favorite artists, a pioneering British contemporary artist. Her use of geometric forms across a surface actively engages and creates the sensation of vibration and movement. I admire the perspective Riley has on her own work. She once said, “My aim is to make people feel alive,” and her work certainly does that.

Her inclusion in the 1965 exhibition “The Responsive Eye” at MoMA gave her overnight celebrity status worldwide. Her work gave viewers a new way of seeing things. I really enjoy living with this remarkable series of early drawings. This period of Riley’s work embodied the goals of that decade, an era of change in all aspects, especially in regard to visual perceptions.

I recall an interview in which Riley described her early attempts at painting looking over the landscape near Siena in Tuscany and the shimmering heat of the day. Perhaps these works are appropriately placed in my home in that regard, as often I turn from the drawings to look out over the shimmering, sparkling bay in Melbourne.

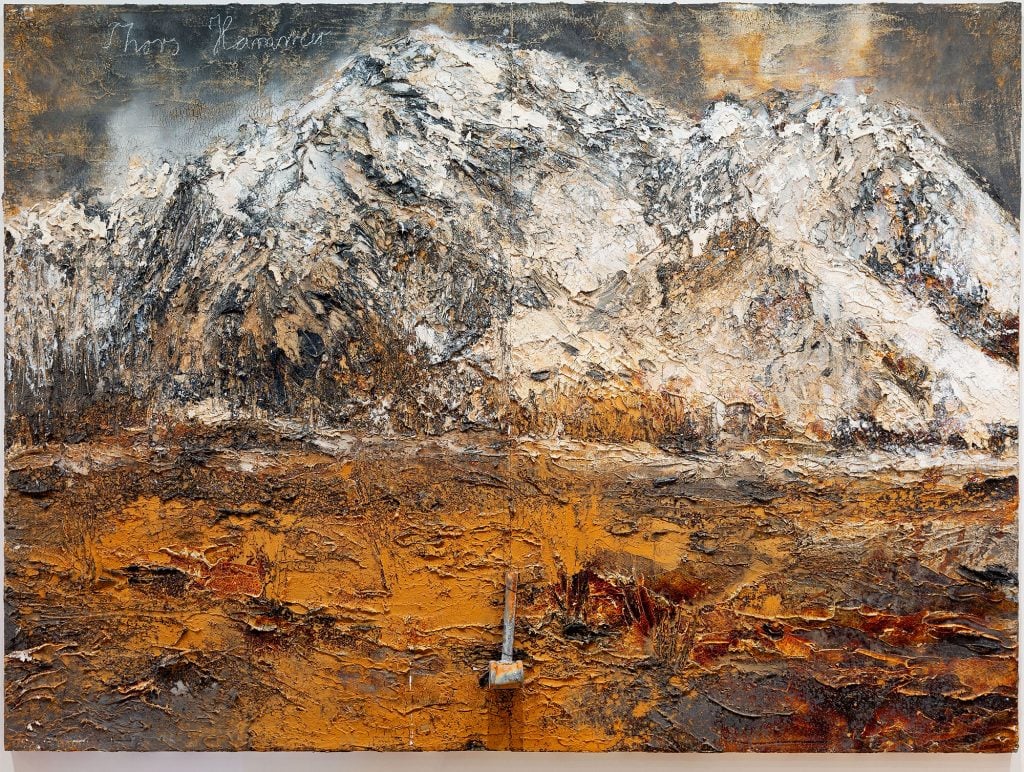

View of Naomi Milgrom’s sitting room with (left) Anselm Kiefer, Thor’s Hammer (2011), © The artist, and (far wall) Tacita Dean’s The Line of Fate (2011), and Ugo Rondinone’s The Sun (2010) through the window. Photo: Christian Capurro. Courtesy of Naomi Milgrom.

What work do you have hanging above your sofa?

Probably the most monumental work in my collection is the one that sits directly on top of my living room sofa. Anselm Kiefer is an artist whom I greatly admire. So much has been written about Kiefer and how he has devoted himself to an artistic practice that sees him reckoning with German history, mythology, literature, identity, and architecture. In my view this work is an outstanding example of his practice.

Every time I walk into the room, I’m overwhelmed by this picture’s majestic presence—the texture, the color, the depth, the strong physicality of the work. I just love it!

Anselm Kiefer, Thor’s Hammer (2011), © The artist. Photo: Christian Capurro. Courtesy of Naomi Milgrom.

What is the most impractical work of art you own?

I had long been interested in Richard Serra’s work, particularly his earlier work. My challenge was to find a domestic scale work that would be suitable in my garden at home and secondly to transport it all the way to Australia.

In 2013 there was one Serra work being sold as part of an estate in Philadelphia. I was in New York at the time and able to arrange to view the work on site in the private gardens of the house where it had been installed in 1988. The sculpture was in a secluded wooded area of the garden and looked irresistible in the dappled afternoon light.

Richard Serra, L.A. Cone (1986). Photo: Christian Capurro. Courtesy of Naomi Milgrom.

Buying the work was the easy part, transporting to Australia much harder. The sculpture, which is 4.2 meters by 5.2 meters (and weighs approximately 13 tons), would not fit into a shipping container so had to be placed top-loaded on a freighter. Then once it reached Australia, it had to be placed on an oversized truck to be transported to my garden. Then using a huge crane had to be lifted into place on the concrete footings specifically built to the Serra studio instructions.

The work looks exactly as it did in the garden in Philadelphia. Even the markings from the original gardeners where the mower handle had brushed the surface are still visible.

What work do you wish you had bought when you had the chance?

Louise Bourgeois. I had my heart set on a work called Untitled (Love) executed in 2000 but it was not to be. Someone pipped me to the post!

Another work, a black-and-white oil by Bridget Riley, was a big miss for me. I simply couldn’t afford it.

If you could steal one work of art without getting caught, what would it be?

Good karma means more to me than ill-gotten gains! The world is full of amazing works of art from so many periods and places, and I’m blessed to live with the works I have now. Your question reminds me of something I believe Sol LeWitt once said, if I may paraphrase: A great work of art belongs to history, the owner is simply a temporary custodian.