Museums & Institutions

New York’s Natural History Museum Returns Ancestral Remains to Native Communities

Although an amendment to NAGPRA has hastened the return of some items, many tribes are still waiting for updates.

Although an amendment to NAGPRA has hastened the return of some items, many tribes are still waiting for updates.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

The American Museum of Natural History in New York has provided the first major update on its progress since announcing its intention last October to remove from display and repatriate its extensive collection of human remains and associated funerary objects.

According to an internal letter quoted in the New York Times, president Sean Decatur told his staff that the museum “has held more than 400 consultations, with approximately 50 different stakeholders, including hosting seven visits of Indigenous delegations, and eight completed repatriations.”

Under the Biden administration, a recent amendment to the Native American Graves Protect and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) has put mounting pressure on U.S. museums to expedite the return of these highly sensitive, contested collections. The legislation was introduced in 1990 and requires federally funded institutions to return Native American cultural items. In the decades since the act was enforced, however, it has been criticized for effecting only slow progress.

In October, the American Museum of Natural History said it had the the human remains of about 12,000 people, of which a quarter are Native American. Of these, 2,200 skeletal remains are managed by the institution’s Cultural Resources Office and appear to be the principal focus for repatriation efforts. Decatur revealed that, so far, 124 have been returned (1,000 had already been repatriated in the prior decades since NAGPRA was first enacted.)

Further to this, 90 tribal funerary objects have so far been repatriated. One group of six objects that were excavated in 1899 and entered the museum’s collection in 1900 were among those that have already been identified for repatriation to the Delaware Nation, Oklahoma; Delaware Tribe of Indians; Shinnecock Indian Nation; and the Stockbridge Munsee Community, Wisconsin. These objects include two stone chips, one lot of small potsherds, one lot of shells, one lot of faunal material, and one broken bone awl.

The newly revitalized Northwest Coast Hall at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City was unveiled in 2022. Photo: Alexi Rosenfeld/ Getty Images.

The museum still holds thousands more objects that Indigenous communities are waiting to reclaim. One example is a sacred Ohtas, a small wooden doll, which is not currently on public display. Museum officials have been consulting with representatives of the Munsee-Delaware Nation about the doll’s future since 2021.

Joe Baker, a member of the Delaware Tribe of Indians who lives in Manhattan, expressed the urgency of these negotiations to the Associated Press: “The collections, they’re part of our story, part of our family. We need them home. We need them close.”

Another contested object that remains in storage at the American Museum of Natural History is a book of drawings by the Cheyenne warrior Little Finger Nail that records his experiences on the battlefield. When he was killed by U.S. soldiers in Nebraska in 1879, the book was taken from his person and, with it, a document of “the actual history of the Cheyenne and Arapaho people,” according to Gordon Yellowman, who oversees the tribes’ department of language and culture and believes that museums can find new solutions for exhibiting contested historical objects, such as creating digital replicas.

The American Museum of Natural History did not respond to a request for further comment on when the Ohtas or Little Finger Nail’s sketchbook would be returned. Decatur told AP that tribes would hear from the museum “soon.”

Museums’ management of their collections of Native American human remains and funerary objects has come under greater scrutiny this year, following federal regulations introduced in December 2023 to strengthen NAGPRA. The act was previously criticized for allowing museums to get away with carrying out the necessary research for repatriation at a slow pace. The amendment aims to give Tribes more authority over this process.

Additionally, it gives museums five years to update their inventories of human remains and funerary objects and improve transparency around these collections. This work of establishing cultural affiliations between human remains and specific tribes provides the necessary information for Indigenous communities to make repatriation claims.

Museums must also obtain proper consent from Native American tribes and lineal descendants of Native Hawaiian Organizations before displaying remains and cultural objects.

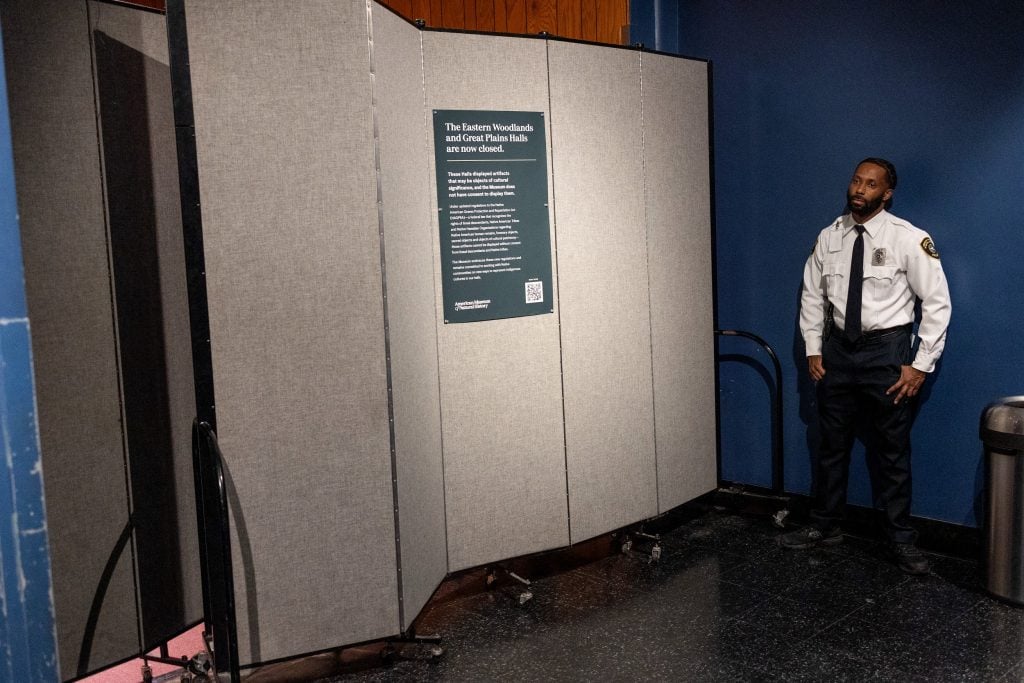

The first day of the closure of the American Museum of Natural History Eastern Woodlands and Great Plains indigenous exhibition halls on January 27, 2024 in New York City. Photo by Andrew Lichtenstein / Corbis via Getty Images.

Earlier this year, the American Museum of Natural History joined institutions like the Field Museum, Cleveland Museum of Art in Ohio, and Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in closing or covering sensitive displays. The Peabody Museum reopened its North American Indian hall after removing sensitive objects. Meanwhile, the Cleveland Museum was recently able to redisplay artifacts after receiving consent from the Tlingit people.

“This is not a prohibition against research or exhibits—quite the opposite,” Shannon O’Loughlin, head of the Association on American Indian Affairs, told Artnet News in February, after several museums took displays off view. “Just speak with any institution that has followed NAGPRA’s requirements and repatriated. They have built long-lasting relationships with those Native Nations and have developed strong exhibitions and research based on that consultation and collaboration, which includes the expertise and knowledge of Native Nations that science has ignored.”

The American Museum of Natural History closed two galleries, the Eastern Woodlands and the Great Plains, that will eventually be entirely reconstructed. In 2022, the museum unveiled its new $19 million Northwest Coast Hall, which had been renovated in close collaboration with tribes.

“The Halls we are closing are vestiges of an era when museums such as ours did not respect the values, perspectives, and indeed shared humanity of Indigenous peoples,” the museum said in a statement on January 26. “Actions that may feel sudden to some may seem long overdue to others.”

To contextualize this new approach for the general public, the American Museum of Natural History plans to open an exhibition this fall that will trace the history of NAGPRA.