Last February, about a month after Naomi Beckwith was officially named chief curator and deputy director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, she sat down for a television interview with local news station NY1.

Invited for a segment addressing “the push to make the [art] industry more inclusive as the fight for racial justice continues,” Beckwith spoke at length about her role as one of the advisors for “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” an exhibition first conceived by the late curator Okwui Enwezor. The show was organized as an articulation of how societal injustices can often lead to grief; a grief that Beckwith has no doubt felt at times during her life; a grief that almost all Black people can easily find and name. The “Grievance” part of the exhibition’s title referred to how that grief is co-opted by white America.

When we talk about Beckwith’s historic arrival at the Guggenheim, many have been conditioned to interrogate the reasons behind the museum’s decision to hire her when they did. But maybe we should focus instead on asking why Beckwith, understanding the industry as well as she does, believes that the Guggenheim is the right place for her to be.

Within the old paradigm of elite institutions as bastions of unadulterated power and prestige, the answer might be obvious. But within this new one, where we’re chipping away at how privilege and agency are distributed at nearly every level of the industry, starting from even the fundamentals of how museums engage with their audiences, the answer is much more expansive. The story becomes about how the Guggenheim will benefit from someone who is as uniquely equipped as she is to usher in this very necessary realignment of its institutional priorities—along with preserving all that we love about the institution in the process.

A view of the exterior facade of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City. Photo by Ben Hider/Getty Images.

In describing her attitude toward museum work, Beckwith often resorts to an anecdote. The painter “Frank Bowling writes very intentionally about how it is so important to be committed to change from the inside,” she says, before offering a metaphor the artist Melvin Edwards once shared with her. Referring to a barbed-wire installation of his, he said: “You’re going to get nicked, you’re going to get cut sometimes, you’re going to bleed sometimes,” she paraphrases. “But you’ve got to be prepared for that. Because the reward of having walked through that barbed wire should be far greater not just for yourself, but for the entire field and for history, than just insisting that there’s a better way. You’ve got to demonstrate a better way. And you have got to put in that work at the place where it needs to be done.”

In her first extensive interview since she began at the Guggenheim, Artnet News spoke with Beckwith about how she identifies artists who matter, how trustees shape the culture of an institution, and why we need to change the way we think about art.

You’ve come on board at a pretty tough time for art institutions, given the pandemic. We know the Guggenheim has made its name doing really ambitious geographical deep dives, so I wanted to start a question about that: Will these kinds of projects be possible going forward?

The pandemic is a logistical challenge for everybody. There’s a way in which these kinds of limits on travel have been a boon to the environment, and one of the things that the Guggenheim was really focused on is sustainability.

That said, it doesn’t mean it’s not possible, these deep dives into a global art practice. Here in New York, we have incredible public and private collections that represent a spectrum of global conversations, and we can pull those works from across the country and from people within their own communities. I’m deeply interested not only in our previous commitments to Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America, but looking toward southern Saharan Africa.

It’s also been a great moment to look across the United States. You’ll see exhibitions on the calendar with artists like [Beirut-born, Syrian American artist] Etel Adnan, who’s on the West Coast. We are still able to have global conversations even if we can’t grab everything from across borders.

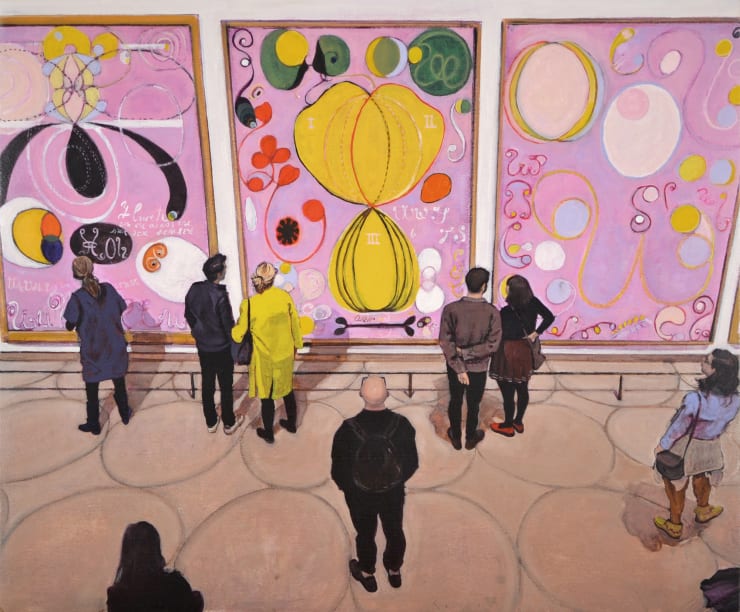

Joe Fig, Hilma af Klint: The Ten Largest, Adulthood #6, 7 & 8/Guggenheim (2019). Photo courtesy of Cristin Tierney.

A lot of times, the global can overshadow what’s happening within the continental United States. Will there be a bit of a shift, with more of a focus put on some of the communities in this country?

It’s easy to say that the short answer is yes, but, you know, I’m less interested in, let’s say, “We’re going to focus on x, y, and z across the Americas” and more in how we can tell stories about new understandings of abstraction. Like Hilma af Klimt [who was the subject of a major 2018 Guggenheim exhibition], right? How can we rethink some of the prescribed narratives that we’ve inherited in the world? For me, there’s a trajectory from someone like Klimt all the way up to [contemporary American artist] Howardena Pindell. To really put women at the center of abstraction, or even rethink some of the stories that we’ve heard around abstraction being about form, when in fact we can talk about all sorts of things.

I’m also really interested in those histories, especially across the ‘60s and ‘70s, that allow us to think afresh about how our art came to be. I worked on the exhibition “The Freedom Principle: Experiments in Art and Music, 1965 to Now” while I was in Chicago [at the city’s Museum of Contemporary Art]. I was really interested in the way I could bring these alternative histories, these lesser-known histories—at least outside Chicago—to a broader world. But I was also really interested in how this show gives us another way of thinking about collaborative practice, rather than the usual story of the lone genius in the studio cutting off their ear.

How can we possibly imagine how art is deeply embedded in the social? And has a responsibility to community? One thing that really excites me about the Guggenheim is that those were the core stories of the founding.

Will the Guggenheim be willing to take any chances on lesser-known names?

We are always interested in who you would call the lesser-known names. And that isn’t necessarily even about the big show, right? The grand rotunda. Because oftentimes, younger artists or more emerging artists don’t have the oeuvre behind them for some of these grand spaces. So this comes by the way of performance, of programs, of collecting.

But what’s more important for me is not to overly valorize the new, or giving an audience the first look. It’s really important to set up exhibitions and books and programs that are about the opening salvo in an artist’s ongoing career.

“Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Fly In League With The Night” at Tate Britain 2020. Photo: Tate. (Seraphina Neville).

I know you have a long history dating back to the Studio Museum of doing this, but could you get into the nitty gritty of how you make sure emerging and underrepresented voices get the scholarship they need to have that long-lasting support within institutions?

First, by asking not only if an artist makes something interesting to look at, but what proposition is this artist putting into the world? And how can it change the way we think about our history? When I did a show of [British painter] Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, I remember specifically thinking that this is an artist who is giving us figuration, and inside that figuration, she’s absorbing both the history of abstraction and the history of representational art together—let alone the brilliant things she was doing around the presence of Black bodies. So we can start breaking down some of these perceived wisdoms: the way pieces are received and how we think about our categories altogether. That’s how you know you’re dealing with an artist who has some kind of staying power.

It seems as though museums collaborating together could advance that mission. Are there any concrete opportunities that you’re looking at right now to collaborate across New York or across the country?

It’s easy to overstate the competitiveness. This is a field full of colleagues that I deeply, deeply respect, no matter what institution they’re in. So we’re constantly sharing ideas and information.

This is a moment in the pandemic when we realize that institutions in general have to work together, a little bit more tightly, whether it be about sharing shipping costs, being flexible on calendars, or being judicious and generous about shows.

You’ll also see these ongoing conversations with museum directors that are really about lobbying for this field and for the art industry in a moment when we’ve lost so much revenue and need to do the work of appealing to state and national governments to support the arts.

The front steps of the MCA Chicago, where Beckwith worked as senior curator. Photo by Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago

You had mentioned that you want a reinterpretation of the collection to be in alignment with DEAI goals. Is there anything you can share right now about how you plan to do that?

Without a doubt, we are committed as an institution to our very specifically-stated DEI goals, putting BIPOC artists front and center, with an emphasis on Black Indigenous work. These are areas where we realize we as an institution can dive much deeper and build out the collection.

But as I’ve said before, it’s important to me to not just have what’s called representational diversity. I do want a number shift, but that is a very long-term game. What I’d also like to see shift is the way we talk about each individual artist, not in relation to a majority art form, but regarding their importance in and of themselves—to think again about how their contribution individually has changed the way that we think about art.

I had a very interesting conversation with former Studio Museum in Harlem director Lowery Stokes Sims about deconstructing art histories in our canon. She said something like, “You know what they say, the art canon is like a rubber band—you can only stretch it so far before eventually it snaps back.”

Yes, it snaps back, but it’s a malleable thing. I don’t think it will go back to that same shape. I don’t think it can anymore. I truly feel optimistic at this moment in time. There’s too many of us—however you define us: those who are progressive, those who consider ourselves socially engaged art historians, those who consider ourselves concerned with BIPOC artists, those who consider ourselves feminists. There’s too much information out in the world to have it go back to the way it was.

You’ve said before that you’ve thought deeply about how institutions are run—by whom and for whom. That’s probably aligned with a lot of things you are discussing here.

I am reminded of something that I love by the late, great Okwui, who would always say that he was interested in the mistakes that institutions have made. Because I think it’s very easy to locate a problem inside an institution and condemn it based on that. But what if, like Okwui, and especially like myself, you are actually committed to institutions? If you think they have a place in our society and you want them around in the future, then you take what’s been termed as a mistake as actually a site of agency.

Ellen Gallagher, Dew Breaker (2015), included in the New Museum’s “Grief and Grievance” show. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

That’s contingent on the institution, because you need to be in a supportive environment in order to do that. And you’ve noted that your relationship with the Guggenheim is more of a partnership with respect to making these changes. Maybe you want to elaborate on that?

Look, it starts at the top, and top doesn’t mean the director—it’s trustees. It’s about finding an alignment with these goals throughout the institution, from our funders to the custodians.

If we have a vision for shaping the future and we want to be relevant to that future, we have to bring a more equitable world into being. What’s wonderful is that I feel like I’m in an institution that understands that that needs to happen.

A source once told me that the late art historian David Driskell’s seminal exhibition spawned a whole generation of African American curators, and we need to realize that they’re not necessarily trying to change the conversation within these institutions—what they’re actually trying to impact is history.

I mean a lot of critique and criticism of institutions has been that they are mired in the past, that they are inflexible and it’s a constant looking back. I don’t think that’s the case at all. I think every institution is not only concerned with its individual legacy, but also concerned for the far-reaching legacy of the artists that they show.

I believe in cultural heritage and I believe in the fact that there needs to be a place not only where these objects are held, but where we tell those stories, and we continue to recast those stories over and over and over again.